Archive for the ‘advertising’ Category

Consumers’ Right to Information

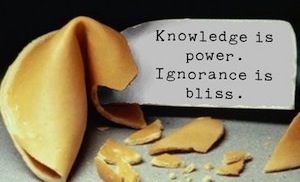

Over on my Food Ethics Blog, I recently posted a piece on the oft-proclaimed “right to know what I’m eating.” That right is often asserted, but seldom explained. Do we have a right to know everything about what we’re eating? Basically I argue that rights are a very serious kind of moral mechanism, to be used only to protect our most important, central interests.

Over on my Food Ethics Blog, I recently posted a piece on the oft-proclaimed “right to know what I’m eating.” That right is often asserted, but seldom explained. Do we have a right to know everything about what we’re eating? Basically I argue that rights are a very serious kind of moral mechanism, to be used only to protect our most important, central interests.

Now, that blog entry was specifically about the right to know about your food. The (claimed or actual) right to information about your food is of course just one among many (claimed or actual) rights for consumers to know things about the products they’re buying.

Now, sometimes rights arise from government action: under food labelling laws in Canada and the U.S., for example, consumers have a right to know the basic nutritional characteristics — including calories — of the packaged foods they buy. So, does this right follow the pattern I suggested above? Is knowing the precise caloric content of a serving of Special K, or the amount of niacin it contains, essential to protecting or promoting my central interests? Clearly not. But take note: I’m not at all saying it’s not useful information; it clearly is. But people did manage to get by in life prior to such labelling rules. So having that information isn’t essential to protecting an individual’s interests.

Now, some will think this is a counter-example to the (very basic) theory of rights I proposed in my food info blog entry. Here, we have a socially-acknowledged right to a piece of information (calories in your breakfast cereal), despite the fact that it’s a piece of information that is hardly essential to my well-being.

But I think a better lesson can be drawn, here, and that’s that well-justified consumer-protection laws (like nutritional labelling laws) aren’t necessarily designed to protect the rights of individuals. They’re better thought of as being designed to promote the well-being of populations. Knowing how many calories are in a bowl of Special K might not be essential to protecting my interests. But (so the thinking goes) there’s a good chance that forcing companies to reveal that information will result in a more calorie-aware population, which is a good result.

The distinction ‘under the hood,’ here, is an important one. Sometimes we attribute rights to individuals (e.g., the right to a piece of information) because we think that right is owed, morally, to that person. And sometimes we attribute rights to individuals instrumentally, as ways of achieving broader social goals.

—–

Addendum:

I’ll likely return to this set of issues soon. There are lots of things consumers have an interest in knowing. For example, I’d love for the stereo salesperson at Best Buy to tell me if a competitor sells the same item cheaper. Do I have the right to that info? Stay tuned.

Back to Playboy…errrr School

Marketing to kids is always a touchy subject. But even worse is when a company accidentally markets to kids. And when you accidentally market to kids something that is seriously adult-oriented…watch out!

Marketing to kids is always a touchy subject. But even worse is when a company accidentally markets to kids. And when you accidentally market to kids something that is seriously adult-oriented…watch out!

Check out this story, from the Globe & Mail‘s Business section: Firm regrets back-to-school ad for Playboy thongs, bras

Giant Tiger, a discount retailer with outlets across Canada, says it made a big mistake when it marketed Playboy-branded underwear in a back-to-school flyer. Many parents complained to the retailer over the ads for bras, thongs and other items with Playboy’s logo.

…

Giant Tiger has apologized to the parents, and Playboy, according to the news agency, is working with the retailer to ensure that such items are aimed at women over 18. Playboy, the spokeswoman said, has strict rules that prohibit marketing to minors….

Now, the actual offense here is pretty modest (no pun intended). And there’s every reason to believe both companies when they say it was all a mistake.

I wonder if this is another, quite different, kind of example of the little ethical lapses (or lapses in quality more generally) that can occur when things are done cheaply. (For those of you not familiar with the chain, Giant Tiger stores are a couple of notches down-scale from Walmart, in most regards. Discount products, cheaply displayed.) Without casting aspersions on the skill or judgment of the workers who put together Giant Tiger’s flyers, I have to wonder whether slips of this kind aren’t more likely at bargain-basement retailers. If you shop at GT, you’re either shopping there because you can’t afford to shop somewhere more fancy, or you’re choosing to in order to save money to spend on other things. And, at risk of overgeneralizing, if you want stuff cheap, you’re going to get things done cheaply. Sweatshop labour may be the most high-profile result, but you’re also going to get things like shoddy marketing. On the other hand, I wonder if this could have happened at that most famous of discount retailers, Walmart? They’re famous for cutting costs, but they’re also famous for efficiency.

When Companies “Play Games” With Prices

Is it ethical for companies — without deception — to make use of well-documented human tendencies and weaknesses in order to get us to buy more? Social scientists have long been aware that humans are subject to a range of cognitive biases that affect the way they think in fairly predictable ways. And, apparently, smart marketers know it, too.

Is it ethical for companies — without deception — to make use of well-documented human tendencies and weaknesses in order to get us to buy more? Social scientists have long been aware that humans are subject to a range of cognitive biases that affect the way they think in fairly predictable ways. And, apparently, smart marketers know it, too.

For instance, check out this critique of Apple’s pricing, by Ben Kunz: “How Apple plays the pricing game”

Economist Dan Ariely, author of Predictably Irrational, gives the classic example of a Realtor who shows you a home that needs a new roof, right before taking you to a higher-priced house she really wants to sell. It’s hard to tell if a $400,000 colonial is a good deal – but compared with a $380,000 home that needs work, it looks quite good. Now consider, $499 for an iPad? Well, compared with a smaller one with fewer features, it suddenly looks great.

Decoys explain why Apple often sells each gadget in a pricing series, such as the new iPod Touch’s $229, $299, and $399 price points for different storage capacities. You may gladly spend $229 to get a hot media player, thinking it’s a deal compared with the highest-priced version and not blink that you could instead buy an iPhone 4 at the lower price of $199 with more features.

(Don’t put too much stock in the details of the prices quoted — as one of the comments under the article points out, Kunz may be comparing apples & oranges by comparing retail prices for iPod Touch to the discounted iPhone price that you get when you sign a 3-year contract with a phone company.)

At any rate, practices like the ones Kunz describes are by no means unique to Apple. Many restaurants, for example, will include one or two high-priced entrees. I’ve heard it said that those, too, are “decoys.” The restaurant doesn’t expect to sell much of the $35 Surf’n’Turf, but the fact that there is a $35 entree makes the $25 entrees look very reasonably-priced. Now notice that there’s no actual deception, here…just a reliance on the fact that most people will have their choices swayed by such pricing.

Here’s the short version of the case for such practices: Look, there’s no deception here. And consumers still have free will. And there’s no clear difference between using this kind of so-called “trick” and the “trick”, known by salesmen since time immemorial, that people will buy more stuff if you smile and are polite to them. The relationship between buyer and seller is an adversarial one, so buyer beware. (Notice also that a company can accidentally, unintentionally engage in such pricing. Maybe the restaurant really thought the #35 Surf’n’Turf would sell well. But it didn’t, and so the net effect is that the dish ends up acting as a decoy, but it’s hardly something you can blame the restaurant for.)

Here’s the short version of the case against such practices: The cognitive biases that such pricing preys upon are so strong that they effectively limit consumer autonomy. Preying upon them is therefore wrong. We put limits on marketing to young children, because we realize that young children aren’t fully capable of filtering messages, evaluating options, and choosing rationally. But the (sad) news from the psychological literature is that adults are likewise limited. We just aren’t as rational or autonomous as we think we are. Selling crack to a crack addict is unethical in part because the addict has no choice but to buy. She doesn’t rationally choose to buy the crack: her addiction ensures the sale. Now, cognitive biases of the kind describe above aren’t quite like addictions. But if a given cognitive bias is only effective “most” of the time (as opposed to an addiction’s near certainty) doesn’t the fact remain that the person doing the selling is relying on a kind of human compulsion, rather than on a rational choice that is likely to satisfy the consumer’s needs?

—

If you’re interested in this stuff, I highly recommend Dan Ariely’s book, Predictably Irrational. See also Judgment under Uncertainty: Heuristics and Biases, by they guys who basically invented the field, Daniel Kahneman, Paul Slovic, and Amos Tversky.)

Interview: Andrew Potter and The Authenticity Hoax

My pal Andrew Potter is a public affairs columnist with Maclean’s magazine (Canada’s premier newsweekly) and a features editor with Canadian Business magazine. He also has a Ph.D. in Philosophy.

My pal Andrew Potter is a public affairs columnist with Maclean’s magazine (Canada’s premier newsweekly) and a features editor with Canadian Business magazine. He also has a Ph.D. in Philosophy.

Andrew’s new book, The Authenticity Hoax, is excellent. I interviewed Andrew recently, about the implications the issues discussed in his book have for a range of topics in Business Ethics.

————–

Chris MacDonald: Your new book, The Authenticity Hoax, is about the way our pursuit of authenticity is in many ways the pursuit of a mirage, and you argue that the pursuit of it is ultimately not just futile, but destructive. You say that one element of that — or is it a result? — is a lack of faith in the market. Presumably that plays out, in part, in a perception that business quite generally is unethical, on some level. Is that one of the deleterious effects of the pursuit of authenticity?

Andrew Potter: According to the theory I offer in the book, the quest for the authentic is largely a reaction to four aspects of the modern world: secularism, liberalism, technology, and the market economy. And I think you’re right, that hostility towards the market is probably the most significant of these. Why is that? That’s a whole other book! Though I think something like the following is at work:

First, markets are inherently alienating, to the extent to which they replace more gregarious and social forms of interaction and mutual benefit (e.g. sharing or gift economies, barter, and so on) with a very impersonal form of exchange. The second point is that the market economy is profit driven. This bothers people for a number of reasons, the most salient of which is that it seems to place greed at the forefront of human relations. Additionally, the quest for “profit” is seen as fundamentally amoral, which is why — as you point out — the mere fact of running a business or working in the private sector is considered unethical. Finally, you can add all the concerns about sustainability and the environment that the market is believed to exacerbate.

The upshot is that we have a deep cultural aversion to buying things on the open market. We think we live in a consumer society, but we don’t. We live in an anti-consumer society, which is why we feel the need to “launder” our consumption through a moral filter. That, I think, is why so much authenticity-seeking takes the form of green- or socially conscious consumerism.

CM: Claims to authenticity are a standard marketing gimmick at this point. In The Authenticity Hoax, you argue that authenticity isn’t the same as truth. Authenticity has more to do with being true to some essence, some deeper self. It strikes me that that makes for some very slippery advertising, including lots of claims that can’t be backed up, but can’t be disproven either. Is authenticity the ultimate marketing gimmick that way?

AP: Absolutely. What advertising and politics have in common is that they are both “bullshit” in the philosophical sense of term (made popular by Harry Frankfurt). What characterizes bullshit is that it isn’t “false”, it is that it isn’t even in the truth-telling game. That is why I think Stephen Colbert was dead on when he coined the term “truthiness” to refer to political discourse — he essentially means that it is bullshit.

What is interesting is that authenticity has the same structure as bullshit, in the following way: from Rousseau to Oprah, the mark of the authentic is not that it reflects from objective truth in the world or fact of the matter. Rather, the authentic is that which is true to how I feel at a given moment, or how things seem to me. As long as the story I tell rings true, that’s authentic.

And that fits in well with advertising, since advertising is all about telling a story. Everyone knows that most advertising is bullshit — for example, that drinking Gatorade won’t make you play like Jordan, or that buying a fancy car won’t make you suddenly appealing to hot women. But what a good brand does is deliver a consistent set of values, a promise or story of some sort, which fits with the idealized narrative of our lives, the story that seems true to us. That is why branding is the quintessential art form in the age of authenticity. Bullshit in, authenticity out!

CM: There’s an irony, of course, in the fact that so many companies are making claims to authenticity in their advertising and PR, since for most people the very term “PR” implies a kind of spin that is the exact opposite of authenticity. But that apparent irony echoes a theme from your previous book, The Rebel Sell (a.k.a. Nation of Rebels), doesn’t it? In that book, you (and co-author Joe Heath) argued that all supposedly counter-cultural movements and themes — things like skateboarding, hip-hop, environmentalism, and now add authenticity — are bound to be co-opted by marketers as soon as those ideas have gathered enough cultural salience. Is that part of what dooms the individual consumer’s pursuit of authenticity?

AP: Yes, that’s exactly right. Chapter four of my book (“Conspicuous Authenticity”) is a deliberate attempt to push the argument from the Rebel Sell ahead a bit, to treat “authenticity” as the successor value (and status good) to “cool”.

We have to be a bit careful though about using the term “co-optation”, because it isn’t clear who is co-opting whom. Both cool-hunting and authenticity-seeking are driven not by marketers but by consumer demand, in particular by the desire for status or distinction. And in both cases, the very act of marketing something as “cool” or as “authentic” undermines its credibility. Authenticity is like charisma — if you have to say you have it, you don’t.

That doesn’t mean marketers can’t exploit the public’s desire for the authentic, but it does mean they have to be careful about the pitch they employ; it can’t be too self-conscious. We all know that “authentic Chinese food” just means chicken balls and chow mein, which is why I actually think that things that are explicitly marketed as “authentic” are mostly harmless. It’s when you when you come across words like “sustainable”, or “organic,” or “local” or “artisanal”, you know you’re in the realm of the truly status-conscious authentic.

CM: I’ve got a special interest in ‘greenwashing.’ It occurs to me now that accusations of greenwashing have something to do with authenticity. When a company engages in greenwashing, they’re typically not lying — they’re not claiming to have done something they haven’t done. They’re telling the truth about something ‘green’ they’ve done, but they’re using that truth to hide some larger truth about dismal environmental performance. When companies greenwash, they’re using the truth to cover up their authentic selves, if you will. Do you think the public is particularly disposed to punish what we might think of as ‘crimes against authenticity?’

AP: I’m not sure. It is certainly true that in extreme cases of corporate bad faith the public reacts badly. The case of BP is a good example; as many people have pointed out, its “Beyond Petroleum” mantra is a very tarnished brand right now, and it is doubtful they’ll be able to renew its polish.

But at the same time, I don’t see any great evidence that the public as a whole is disposed to punish companies for greenwashing. Actually, I think the exact opposite is the case: I think the public is very much disposed towards buying into the weakest of greenwash campaigns. The reason, I think, goes back to the point I made earlier about most of us being fairly ashamed of living in a consumer society. Yet at the same time we like buying stuff, especially stuff that makes us feel good about ourselves and morally virtuous. Even the most half-witted greenwashing campaign is often enough for consumers to give themselves “permission” to buy something they really want.

CM: Let’s talk about a couple of product categories for which claims to authenticity are frequently made.

First, food. You argue that much of the current fascination with organic food, locally-grown food, etc., is best understood as the result of status-seeking. So the idea is basically that food elites start out looking down on everyone who doesn’t eat organic. But then as soon as organic becomes relatively wide-spread, suddenly eating organic doesn’t make you special, and so the food elite has to switch to eating local, or eating raw, or whatever else to separate themselves from the masses. And I find that analysis pretty compelling, myself. But a lot of devotees of organic and local foods are going to reject that analysis, and object that they, at least, are eating organic or local or whatever for the right reasons, not for the kind of status-seeking reasons you suggest. And surely some of them are sincere and are introspecting accurately. Does your analysis allow for that possibility?

AP: Sure. The key point is that these aren’t exclusive motivations. In fact, they can often work in lockstep: You feel virtuous eating organic, but you also want to feel more virtuous than your neighbour (moral one-upmanship is still one-upmanship, after all). And so you try to out-do her by switching to a local diet. And when she matches you and goes local too, you ratchet up the stakes by moving more of your consumption to artisanal goods (e.g. small-batch olive oil, handmade axes, self-butchered swine, and so-on).

And this would be a good thing if there were any evidence that these moves actually had the social and environmental benefits that their proponents claim for them. But unfortunately, the evidence is – at best – mixed; the more likely truth is that the one-upmanship angle has completely crowded out the moral calculations.

The more general point is that we need to stop assuming that something that gives us pleasure, or feeds our spiritual needs, will also be morally praiseworthy and environmentally beneficial. That assumption is one of the most tenacious aspects of the authenticity hoax, and it is one that we have no reason to make. There are good and bad practices at the local level, and artisanal consumption has its costs and benefits. Same thing for conventional food production — there are good things and bad things about it. It would be nice if the categories of good versus bad mapped cleanly on to the categories of local versus industrial, but they simply don’t. The belief that they do is nothing more than wishful thinking.

CM: What about alternative therapies? Much of the draw of those products — and at least some of their marketing — seems to revolve around authenticity. People who are attracted to alternative products seem to want to reject modern medicine, which they find alienating, in favour of what they perceive as something more authentic. Now most critics of alternative therapies such as homeopathy primarily object that there just isn’t good evidence that those therapies actually work. But your own analysis provides a further kind of criticism, rooted in the way that those who seek ‘authenticity’ via alternative medicine are engaged in what is more generally an unhealthy rejection of modernity. Is that right?

AP: There is a lot to dislike about modernity, and my argument is not that we should just suck it all up and live with it. My point is rather that modernity is about tradeoffs, and that we need to accept that for the most part, the tradeoffs have been worth making. Yes, some things of value have been lost, but on the whole I think it’s been worth it.

But if there is one part of the pre-modern world that is well lost, it’s the absence of evidence-based medicine. Yet for some bizarre reason, the longer we live and the healthier we get, the more people become convinced that we are poisoning ourselves, and that modern medicine is not the solution to our woes, but part of the cause.

The turn away from the benefits of modern medicine is one of the most disturbing and pernicious aspects of the authenticity hoax. My book has been interpreted by many as an attack on “the left”, but it perplexes me that things like naturopathy, anti-vaccination campaigns, and belief in the health benefits of raw milk are considered “left wing” or “progressive” ideals. As far as I’m concerned, this is part of a highly reactionary political agenda that rejects many of the most unimpeachable benefits of the modern world. We know that naturopathy and homeopathy is a fraud; we know that vaccines don’t cause autism and that public vaccination is the one of the greatest public health initiatives ever; we know that pasteurization has saved countless lives over the years.

But for reasons I cannot fathom, these and many other related benefits are ignored or shunned in favour of an “authentic” lifestyle that is an absolute and utter hoax.

Flexible Ethics in the Wake of Disaster

What do businesses in the tourism industry in areas affected by the BP oil spill owe to customers and potential customers? Or, to put it another way, just how closely do businesses in the stricken region need to adhere to the “usual” ethical rules of commerce?

What do businesses in the tourism industry in areas affected by the BP oil spill owe to customers and potential customers? Or, to put it another way, just how closely do businesses in the stricken region need to adhere to the “usual” ethical rules of commerce?

Many businesses along the Gulf Coast have of course been very hard-hit. At this point, large stretches of the Gulf Coast are essentially unthinkable as vacation destinations, unless you happen to be into eco-disaster tourism. As a result, businesses there are fighting for their lives — all due to circumstances beyond their control, but very much within the control of a certain oil company whose name, by now, is all too familiar.

In such circumstances, businesses are likely to do just about anything to draw what tourists they can. Though I don’t know of particular cases, it wouldn’t be at all surprising to see some companies cutting corners, ethically speaking. For example, imagine a potential vacationer calls up a resort on the fringe of the affected area, wanting to know whether that particular stretch of beach is still vacation-worthy. And imagine that the usability of the beach is borderline. What answer should the owner of the resort give, over the phone? How scrupulously honest does she have to be, when the survival of her business (and the livelihood of her employees) is on the line?

The problem posed by the expectations of tourists and the way those are handled by resort owners is illustrated in this article by Mike Esterl, for the Wall Street Journal: In Alabama, a Fight for Tourists

“This is not what we expected,” said Clint Pope, 27, who drove his family to Gulf Shores from Thomasville, Ala., Friday for a weekend at the beach.

Mr. Pope’s 10-year-old son, Drew, and nine-year-old nephew, Nathan, still swam in this stretch of the Gulf on Friday afternoon, along with other tourists. But nobody was going into the water Saturday.

Now it’s tempting to say that the obligation of businesses to deal honestly with customers (and potential customers) is unchanged by current circumstances. But compare: many people thought that the looting that took place in the aftermaths of both Hurricane Katrina and the earthquake in Haiti was morally excusable. Some said it doesn’t even count as “looting” at all, when you’re fighting for survival. Does that principle hold true when the party in question is a small business owner, rather than an individual consumer? If stealing (within reason) is ethically permissible in the aftermath of a disaster, is bending the truth (or even lying) ethically permissible, too?

Now there are of course differences in the two cases. In the Katrina and Haiti cases, people were literally fighting for survival — it was literally life-or-death. Presumably no one in the Gulf Coast tourism industry is literally going to starve to death. But still, the general question remains interesting: to what extent can ethical rules legitimately be bent, when someone’s interests are seriously threatened?

Soccer Ball Ethics

Amidst all the excitement over the start of the FIFA World Cup, one of the oddest bits of excitement has surrounded the innovative ball being used in the tournament, namely Adidas’ new “Jabulani.” Although the ball was designed to have superior aerodynamic properties, critics have attacked the ball for the particular way it flies though the air. Here, for example, cites Brazilian goalkeeper Julio Cesar as saying “It’s terrible, horrible. It’s like one of those balls you buy in the supermarket.”

Amidst all the excitement over the start of the FIFA World Cup, one of the oddest bits of excitement has surrounded the innovative ball being used in the tournament, namely Adidas’ new “Jabulani.” Although the ball was designed to have superior aerodynamic properties, critics have attacked the ball for the particular way it flies though the air. Here, for example, cites Brazilian goalkeeper Julio Cesar as saying “It’s terrible, horrible. It’s like one of those balls you buy in the supermarket.”

Two things are interesting about this controversy.

One has to do with fairness. The controversy over the Jabulani — the ball that all teams will play with during the tournament — reminds us that the “level playing-field” metaphor so often appealed to in business is a sporting metaphor. It’s a reference to the fact that we think it desirable, generally, to make sure that no team has an unfair advantage. We want a level playing-field because if we play on a hill, one team is seriously disadvantaged by having to attempt to advance the ball up-hill, which requires considerably more effort. The point generalizes to any factors (including changes in the game) that give one side an unfair (dis)advantage. A change in the game is one thing, but a change that creates a differential advantage is quite another. And with regard to the Jabulani, even some critics have admitted that the fact that this change affects everyone equally mitigates the criticism. As English goalkeeper David James put it, “It’s horrible, but it’s horrible for everyone.”

But it’s worth noting the limits of this level-playingfield argument. While it’s true that all teams are subject to the same change, it’s not true that everyone is affected equally. First, it seems to be goalkeepers that are complaining most, suggesting that there’s a differential impact on them compared to other players — and that matters, at very least in terms of the ego of goalkeepers vs the egos of those scoring the goals. (In fact some suspect that this is an intentional outcome of the change in the ball: it will result in more goals, and hence more excitement, hence making it a better TV sport for North American viewers in particular.) Second, it’s not clear that all teams will be affected equally. Particular ball characteristics are liable to suit some teams’ strengths and strategies better than others. So why the “field” may be “level” at a superficial level, we may need to look deeper if we’re really interested in deciding whether this particular change is, in fact, a fair one.

The second interesting thing about the controversy has been the response from Adidas, the company that designed the ball. The response from Adidas has mainly focused on the science, and on pointing out that change is always difficult at first. But Adidas also had a more interesting defence, namely accusing (some) critics of conflict of interest. (See this definition of ‘conflict of interest’.) In particular, the claim is that most of the critics are subject to a possible financial bias. According to this story,

[Adidas spokesman Brueggen] pointed out that if you look closely at the players and goalies making these accusations you’ll notice one common thread among them: the all have contracts with Adidas’ competitors.

Now certainly not all critics have been affiliated with Adidas’ competitors. The soccer-gear website ‘Soccer Cleats 101,’ for example, reviewed the Jabulani back in January, and expressed some of the same concerns. Still, it’s an interesting accusation. And as always with such accusations, interesting questions arise. First, can Adidas’ claim be backed up empirically? If we actually count up the critics and look at what companies they’re sponsored by, will we see the pattern that Adidas claims? If Adidas hasn’t done such a tally (but is simply working from a rough impression) is it fair to make the accusation? Is the suspicion enough? And if we do confirm such a pattern of bias, what’s the specific explanation for it? Is it a matter of players consciously promoting the interests of companies they’re affiliated with, or is it more likely to be a more subtle, subconscious bias? And, finally — setting aside the fact that professional sport is, itself, a big business — what lessons can we learn from this sports story, and apply to the world of business more generally?

(p.s. Those of you with an interest in ethical dimensions of sports should be sure to check out Wayne Norman’s blog, This Sporting Life.)

Galarraga’s Corvette

By now everyone probably knows the background story: Detroit Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga didn’t get credited with the perfect game he pitched last Wednesday, due to a bad call made by the umpire. Fast-forward a day to General Motors tapping into international sympathy felt for Galarraga by giving the ballplayer a red Corvette convertible. A public-relations coup…pure genius, right?

By now everyone probably knows the background story: Detroit Tigers pitcher Armando Galarraga didn’t get credited with the perfect game he pitched last Wednesday, due to a bad call made by the umpire. Fast-forward a day to General Motors tapping into international sympathy felt for Galarraga by giving the ballplayer a red Corvette convertible. A public-relations coup…pure genius, right?

Well, unless you’re given to armchair micromanagement, in which case you slam GM for wasteful spending.

Here’s the story, by the New York Times’ Nick Bunkley: G.M.’s Gift of a Luxury Car Stuns a Few.

A free sports car for a Detroit Tigers baseball player was not among the reasons the government saved General Motors from financial collapse. Nor was a year’s supply of diapers and other gifts for a Minnesota woman who gave birth behind the wheel of a Chevrolet Cobalt.

General Motors has given away both in recent weeks — marketing ploys that would have barely raised an eyebrow in the past. But now that American taxpayers collectively own a majority of the carmaker, executives are learning that there are more than 300 million potential second-guessers out there.

The complaint, of course, is ridiculous. Never mind the fact that it’s so patently obvious, even to those of us who are not experts, that this was a brilliant move by GM. The bigger point here is that most of us (including the critics mentioned in the NYT story) are not experts, either in public relations or in corporate management more generally.

Now, that’s not to say that non-experts can’t express an opinion. (The fact that I have a “Comments” section on my blog essentially constitutes an invitation to experts & non-experts alike to comment.) The point is that shareholders in GM (including, now, indirectly, all U.S. citizens) have little business feeling aggrieved over each and every minor managerial decision, even ones they suspect are misguided. Shareholders hire managers to manage — to make decisions. Courts have long recognized that, once you empower someone to run a business, you basically need to back off and let them do their job. There are exceptions, of course. The American people now hold a major stake in GM, and they should be worried if they see GM managers heading in any truly disastrous directions. But being a shareholder neither qualifies you, nor entitles you, to have a say in day-to-day decision making. So critics of GM’s gift should feel free to play armchair umpire; but they shouldn’t expect anyone to take them seriously.

Unethical Herbal Supplements

Hey, what’s in that bottle of all-natural herbal supplements on your kitchen counter? Are you sure? What will those supplements do for you? Cure all that ails you? Something? Nothing? One way or the other, how do you know? The truth is, you probably shouldn’t feel so certain.

Here’s the story, from Katherine Harmon, in Scientific American: Herbal Supplement Sellers Dispense Dangerous Advice, False Claims

Here’s the story, from Katherine Harmon, in Scientific American: Herbal Supplement Sellers Dispense Dangerous Advice, False Claims

[The lack of evidence for their effectiveness] …hasn’t stopped many supplement sellers from making the false claims and even recommending potentially dangerous uses of the products to customers, according to a recent investigation conducted by the Government Accountability Office (GAO). To obtain a sample of sales practices, the agency got staff members to call online retailers and to pose undercover as elderly customers at stores selling supplements.

Customers were not only told that supplements were capable of results for which there is no scientific evidence (such as preventing or curing Alzheimer’s disease); the advice and information also was potentially harmful (including a recommendation to replace prescription medicine with garlic)….

Some fans of herbal remedies are liable to complain that the relevant government agencies ought to be directing their efforts at the real culprits, namely Big Pharma. Why pick on people who package and sell “natural” herbal products when major pharmaceutical companies are, on a regular basis, found to have engaged in a whole range of dubious and sometimes deadly behaviours? But that’s roughly like a bank robber, upon his arrest, complaining that the cops ought to be out chasing white-collar criminals instead. The fact that embezzlement is a bad thing does nothing to diminish the badness of robbery. Both are wrong, and both are worthy of punishment.

Essentially, what we’re seeing here is history catching up with the makers of herbal supplements. Over the last decades, we’ve imposed increasingly tough rules on the pharmaceutical industry (though those rules still need to be tightened up in various ways). But herbal products are part of the “natural” products industry, and that industry is woefully under-regulated. Indeed, that industry is probably about as well-regulated today as the pharmaceutical industry was, say, 50 years ago.

(p.s. for information about which herbal supplements are and are not backed by good science, see Scott Gavura’s Science-Based Pharmacy blog.)

Authenticity in Advertising

I took this picture in a Banana Republic store in Toronto this morning. This sign on the wall caught my eye, mostly because I’ve been reading my pal Andrew Potter’s wonderful new book, The Authenticity Hoax.

I took this picture in a Banana Republic store in Toronto this morning. This sign on the wall caught my eye, mostly because I’ve been reading my pal Andrew Potter’s wonderful new book, The Authenticity Hoax.

Note the explicit claim of authenticity, in this ad. As Andrew’s book points out, the language of authenticity is increasingly common in advertising today. It’s interesting to ask just what the claim to “authenticity” means in an ad like this, or in any other ad. Here, does it mean these dresses are historical reproductions? Surely not. So there’s no question of interrogating Banana Republic on the accuracy of either their styles or the accuracy of their claims. So what does “authenticity” refer to, here? It seems to be a straightforward attempt to tap into the widely-shared (but, as Andrew argues, ultimately misguided) desire to flee all that is superficial and phony, and get “back” to something more “real.”

Two further things are worth pointing out. One is that here, as is so often the case, finding authenticity seems to require buying something that is a self-proclaimed rip-off from fashions of days gone by. You get “real” through imitation. The other is that Banana Republic (among many others) recognizes that they can’t get away with simply doing something authentic…consumers actually need to be told these clothes are authentic, in order to recognize them as such.

(Watch here for an interview with Andrew Potter, about authenticity and business ethics, coming soon.)

Greenwashing the Tar Sands

Regular readers will know that I have an interest in what’s often referred to as “greenwashing”.

Regular readers will know that I have an interest in what’s often referred to as “greenwashing”.

Here’s a good example. An ad for Suncor (a big Canadian energy company) appeared in a recent issue of Canadian Business Magazine (May 10, p.24). The ad includes the obligatory green imagery (excerpted at left). The text of the ad reads as follows:

“As Canada’s premier integrated energy company, Suncor has achieved success by seening the possibilities. Developing Canada’s oil sands, as well as energy resources from coast to coast and beyond, brings us even more opportunity to take action on environmental issues. Just as innovation made oil sands production viable, new technology is helping us reduce our impact on air, land and water. For Suncor, seeing the possibilities is the first step towards responsible development.”

What makes this greenwash? Well, to start with, there’s the green imagery and allusions. The pretty picture, and the vague reference to “taking action on environmental issues,” etc. Put that against the backdrop of Suncor’s reality: the oil sands (a.k.a. “tar sands”) are an undeniably dirty source of energy, and more generally the company’s environmental record is far from stellar. Now, it’s worth noting that this ad goes beyond mere associative advertising. Suncor isn’t just trying to put its name next to a pretty picture of trees and fluffy clouds. The ad cites stats. In particular, it brags about:

- “45% decrease in GHG [greenhouse gas] emission intensity at oil sands based on progress to to the end of 2008 compared to 1990 baseline.” Sounds good, but is it? How does that compare to other companies? Is that a legislated reduction, or voluntary?

- “22% decrease in absolute water use at oil sands from 2003 to 2008.” Again, sounds good. But while “absolute” (i.e., total) water usage is important, a reduction in that doesn’t necessarily imply an improvement in methods. It could just as easily imply a change in overall production.

- “$750 million actual and planned investments in renewable energy.” Again, a big number. But not quite so big once you consider that Suncor is a company with over $30 billion in revenues each year. And most importantly, notice that the $750 million includes planned investments. In other words, the company is taking credit for stuff it hasn’t done yet, or even (as far as we can tell) started.

So, what’s wrong with the ad? Are there any lies? Not literally, I think. And probably no lies in the sense of false claims that would be actionable under false advertising legislation. Is the misleading? Well, it’s certainly a rather glossy portrayal of a company engaged in a dirty business. So, like other examples of greenwashing, it’s a distraction from the truth. It attempts a bit of sleight-of-hand. Is a stage magician lying when he distracts you with the flowers in his right hand while his left hand dips into his pocket to retrieve the missing coin? No, not really. But then, the magician is offering entertainment, making our lives better. Greenwash offers a form of distraction that does little more than muddy the waters of discourse about corporate environmental responsibility.

(Thanks to Robin Hansen for showing me the ad and pointing out the greenwash.)

Comments (5)

Comments (5)