Archive for the ‘Uncategorized’ Category

Pharma Ad: Not Quite Misleading

Take a look at this pharmaceutical ad. (I’ve blocked out the drug’s name, because it’s not relevant, and because I don’t want to advertise it.)

Take a look at this pharmaceutical ad. (I’ve blocked out the drug’s name, because it’s not relevant, and because I don’t want to advertise it.)

What’s your impression? What kind of drug is this? What kind of settings should it be used in? Obviously you can’t really tell, but what’s your impression>

Would you be surprised to know that it’s an ad for a narcotic pain reliever? Yup, highly addictive. Made by Hawthorn Pharmaceuticals, and approved by the FDA to treat ‘moderate to moderately severe’ pain in children.

Now, I don’t actually know where this ad appeared. I suspect it was in a professional journal or magazine, aimed at physicians — and physicians would know from the mention of hydrocodone in the ad that this is an opiate, and not to be messed with. So it’s unlikely anyone is going to be misled by this ad. But one certainly wants to ask what impression Hawthorn is trying to foster here. Is this really a drug to help your kid through the aches & pains from that karate tournament?

This might be a good illustration of the line between what’s illegal and what’s unethical. If this ad were truly misleading, it would be illegal. As it is, it’s merely ethically questionable.

—

Update

The ad appears on the company’s page about the product.

—

Thanks once again to Pharmalot.

Craigslist to Limit “Erotic Services” Ads

Further to yesterday’s posting about ethically controversial products, here’s a story about a business (Craigslist) facilitating one ethically controversial business (prostitution). It’s a story about a company changing its behaviour in response to legal pressures, but also a story about technology-enabled commerce, technological solutions to social problems, and compromise solutions in the face of diversity of opinion regarding the ethical status of a commercial service.

Further to yesterday’s posting about ethically controversial products, here’s a story about a business (Craigslist) facilitating one ethically controversial business (prostitution). It’s a story about a company changing its behaviour in response to legal pressures, but also a story about technology-enabled commerce, technological solutions to social problems, and compromise solutions in the face of diversity of opinion regarding the ethical status of a commercial service.

Here are the first bits of the story, from the NYT: Craigslist Agrees to Curb Sex Ads:

The online classifieds company Craigslist said Thursday that it had reached an agreement with 40 state attorneys general and agreed to tame its notoriously unruly “erotic services” listings.

Prostitutes and sex-oriented businesses have long used that section of Craigslist to advertise their services.

Early this year, the attorney general of Connecticut, Richard Blumenthal, representing 40 states, sent a letter to Craigslist demanding that it purge the site of such material and better enforce its own rules against illegal activity, including prostitution. The two sides began a series of conversations about what Craigslist could do to prevent such ads.

“They identified ads that were crossing the line,” said Jim Buckmaster, chief executive of Craigslist. “We looked at those ads, we saw their point, and we resolved to see what we could do to get that stuff off the site.”

Just a couple of quick points:

- Note that the solution being adopted is a harm-reduction strategy: Craigslist isn’t going to eliminate its Erotic Services category, just exercise more oversight and accountability. That’s not a criticism, just an observation.

- Note that the solution being proposed is a technical one: Craigslist has the technological savvy & capacity to implement some oversight & accountability mechanisms. It’s a technological solution to a social problem — though, of course, it’s a social problem enabled by technology in the first place.

- Note also that Craigslist is going to be charging a small fee to credit cards of people who post ads in the Erotic Services category. New source of profits? Nope. The company “will donate the money to charities, including those that combat child exploitation and human trafficking.” Why? Presumably to combat charges that their business is promoting not just prostitution, but exploitation. But if that’s true, is a donation to charity the right solution?

- Finally, a question to ponder: from an ethical point of view, how much responsibility does a company bear for the activities it makes possible? This question has vexed Internet Service Providers — often accused of facilitating the exchange of child pornography, for example — for years. Same goes for file-sharing services like Napster. If (if) you believe prostitution is immoral, where does that leave companies that provide goods & services that make prostitution possible? In order to be blameworthy, does a company have to intend, or merely foresee, that its goods & services will be used that way?

Ethical Porn (and other Controversial Products)

Here’s a question: if you think product X is unethical (or maybe just morally “problematic”), can you engage in a constructive discussion about how to make that product more acceptable (while still selling it) or how to sell it more ethically?

Here’s a story & video clip from This Magazine: “The New Face of Porn”. It’s basically a story about “indie” pornography, which is (roughly) porn that is not produced by one of the big porn studios, and which (more often?) attempts to avoid the sexist stereotypes, heteronormativity, etc. common within “standard” porn. In the eyes of the producers and consumers of indy porn, indy porn is ethical porn. Of course, if you think selling images and videos of naked people doing, um, stuff to each other is intrinsically evil, maybe the idea of “ethical” porn will seem outrageous. Or maybe not.

Or think of a product that is socially controversial in another way: tobacco. Tobacco companies kill people (or help them kill themselves, if you prefer). You could argue that tobacco companies are evil. But you could also enquire into the business practices of various tobacco companies, and ask which ones do their (unethical) business more ethically. Do some treat employees better than others? Do some advertise more responsibly than others? If you’re a passionate opponent of that industry, it might be hard to wrap your head around those questions, but it’s worth the effort.

Here’s a thought experiment (or a classroom activity, for you teachers & profs out there). Fill in the blanks in the table below with behavioural examples (i.e., examples of behaviours that would differentiate good, questionable, and evil sellers of good, controversial, and evil products). An easy example: a “good” seller of meth (an evil product) only sells to current addicts, and doesn’t lure new ones into the habit. Stuff like that.

Bereaved Mom Sings Oxycontin Blues on Wikipedia

Ain’t nothin gonna be right no how

Ain’t nothin gonna be right no how

‘Cause I know I can’t ever lose

This devil that’s draggin’ me down

And the oxycontin blues

Those are the final lines of Steve Earl’s stirring 2007 song, “Oxycontin Blues.”

A song just as sad is currently being sung on Wikipedia by one mother whose daughter fell victim to the drug. As reported by Ed Silverman over at the Pharmalot blog:

We all know how Wikipedia works – the definitions and descriptions can be changed by the public at large. Now, Marianne Skolek has defined Purdue Pharma for all the world to see – and in her view, her recent entry helps to set the record straight about its OxyContin marketing.

Skolek, you see, holds Purdue responsible for the 2002 death of her 29-year-old daughter, who was prescribed the painkiller for a herniated disk and wound up dying of heart failure, leaving behind a 6-year-old son. And she remains unsatisfied with a plea deal last year in which Purdue Pharma and three present and former execs agreed to pay $634.5 million to settle charges related to deceiving docs about the potential for abusing OxyContin. No one went to jail….

The details of the case — including especially Purdue’s dangerously deceptive marketing campaign — are shameful. It’s also a good example of how, in the age of the Internet, a single really angry person can take a huge, visible slap at a mighty company.

(The Wikipedia page is liable to get edited again, so here’s a screen-cap of the Purdue Pharmaceutical page on Wikipedia as of 10 a.m. Eastern on November 7, 2008)

Update (9:15 pm)

Not surprisingly, the Wikipedia page for Purdue has now been edited (less than a day later). Skolek’s edits are gone. But you can still see what she wrote via the screen-cap I grabbed this morning: Purdue Pharmaceutical, Wikipedia.

Update #2 (9:30 pm)

Here’s a blog entry I wrote about Purdue last year, before I knew about Ms. Skolek’s case: Purdue Pharma (and Execs) Guilty in OxyContin Case

Philosophy, Ethics, and Jobs

In a recent posting on Ph.D. Programs in business ethics, I noted that one of the main avenues (though certainly not the only one) to a career in business ethics is a Ph.D. in Philosophy. While it would be foolish to claim that Philosophy “owns” ethics, it’s worth noting that, as a topic of study (as opposed to, say, an area of regulatory law), ethics has been a branch of Philosophy for more than 2,000 years. And many (though certainly not all) of the founding mothers-and-fathers of the field of business ethics (most of whom are still alive) are Philosophers. Non-philosophers in the field (including legal scholars, management profs, etc.) typically have either studied some philosophy, draw upon philosophers, and/or work alongside philosophers. I’ll go out on a limb and say that you just can’t do respectable work in business ethics — certainly not respectable scholarly work — without a little bit of philosophy. (Of course I’m biased: my own Ph.D. is in Philosophy.)

In a recent posting on Ph.D. Programs in business ethics, I noted that one of the main avenues (though certainly not the only one) to a career in business ethics is a Ph.D. in Philosophy. While it would be foolish to claim that Philosophy “owns” ethics, it’s worth noting that, as a topic of study (as opposed to, say, an area of regulatory law), ethics has been a branch of Philosophy for more than 2,000 years. And many (though certainly not all) of the founding mothers-and-fathers of the field of business ethics (most of whom are still alive) are Philosophers. Non-philosophers in the field (including legal scholars, management profs, etc.) typically have either studied some philosophy, draw upon philosophers, and/or work alongside philosophers. I’ll go out on a limb and say that you just can’t do respectable work in business ethics — certainly not respectable scholarly work — without a little bit of philosophy. (Of course I’m biased: my own Ph.D. is in Philosophy.)

On a related note: Philosophy’s makeover: Why job prospects for philosophy grads are brightening. Here are the opening paragraphs:

Thirty years ago, British Columbia native Jim Mitchell turned down two job offers to teach at university. Though he had spent years studying philosophy and eventually obtained a PhD from the University of Colorado, he decided he didn’t want to spend the next few decades in one spot. So he started a career in the Canadian federal public service, rising through the ranks to become assistant secretary to the cabinet, where he advised prime ministers on the organization of government.

To his surprise – and delight – he found his studies in epistemology and metaphysics prepared him well for dealing with the complex workings of the federal government. Dr. Mitchell, who eventually left government to become a founding partner of Sussex Circle, a consulting group in Ottawa, is not alone in finding that his degree in philosophy paid off.

This article makes small mention of ethics, which is a bit odd given that ethics is really philosophy’s growth field. Philosophers working in both business ethics and bioethics (and perhaps other areas of ethics, too) very likely have a better chance of finding employment, in universities and beyond, than their colleagues in logic, metaphysics, epistemology, etc.

So, as career advice goes, I could do worse than to suggest, to a young person interested in a job in business ethics, that they should study philosophy. At very least a degree (or two or 3) in philosophy will equip you with some critical thinking skills and a knowledge of the ethical theories that are the stock in trade of serious business ethics. But in all good conscience I should add that, in a world in which a lot of business ethics-related jobs actually have titles implying a connection with regulatory compliance, it’s also a pretty good idea to consider studying either law or accounting.

I don’t have any employment stats to back this up; I’m kind of shooting from the hip. Feel free to comment below if you can help in that regard.

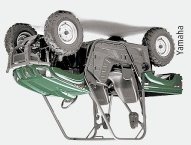

Off-Road Vehicles: How (un)Safe is (un)Safe Enough?

Here’s a quick peek into the complexities of product safety, from a legal, regulatory, and ethical point of view.

Here’s a quick peek into the complexities of product safety, from a legal, regulatory, and ethical point of view.

From the WSJ: U.S. Probes Off-Road Vehicles After a String of Accidents

The Yamaha Rhino, a hit in the off-road-vehicle market, promises to go “almost anywhere” with an “amazingly high level of comfort and ease.” Now, federal safety regulators are investigating the vehicle following reports of some 30 deaths involving it, including those of two young girls last month.

The Rhino also has drawn keen interest from the plaintiffs’ bar: Yamaha faces more than 200 lawsuits in state and federal courts, many alleging the Rhino’s design is unsafe. Yamaha has settled some but recently beefed up its defense and says it may start to fight rather than settle.

Yamaha stands behind the design of the Rhino….

What the story casts as a tough regulatory problem — the lack of regulatory standards for new categories of products — can also be seen as a tough moral problem for manufacturers. Here’s what the WSJ says about the regulatory problem:

The Rhino matter shows how federal safety regulators sometimes struggle to respond to what they call “emerging hazard” areas. There are no regulatory standards for the new breed of off-road vehicles, the CPSC said.

They aren’t subject to ATV safety standards because of design differences such as having a steering wheel, in contrast to the ATVs’ handlebars. But the novel off-road vehicles also aren’t subject to the much-tougher standards for cars. Owners of UTVs don’t have to register them.

“When there is no standard in place, we have to basically determine if there’s a substantial risk of injury and death, and there’s a hurdle there that has to be met,” says Jay Howell, acting assistant executive director of the CPSC’s office of hazard identification and reduction.

This is how consumer regulation often works: Products hit the market governed by no particular safety standards. If injury reports later arise concerning a product, these gradually get the attention of both manufacturers and regulators — often with a spur from lawyers for those injured.

If this poses a challenge for regulators, it also must pose an ethical challenge for well-intentioned companies and the safety engineers who work for them. You need to ask: at what point (as information about the dangers of their product accumulates) would Yamaha have to start changing its designs? At what point should they withdraw their product altogether? Surely one or two injuries are not enough. And in a new product category, benchmarking by comparison with other products may not be very helpful. I point this out not to generate sympathy for poor ol’ Yamaha. Rather my point is that if you’re seriously interested in product safety, you need to do more than react to individual cases.

Starbucks: Free Coffee for Voters?

Most of you will have heard by now that Starbucks stores in the U.S.

Most of you will have heard by now that Starbucks stores in the U.S. are were offering a free coffee to anyone who announced that they’ve voted. (Here’s the Starbucks ad on YouTube.) Some of you will also have heard that this is not exactly legal: U.S. election laws forbid offering incentives for people to vote.

Consensus seems to be that while this is technically illegal, it’s unlikely to result in charges being laid. But still, is it OK for a company to do this? On one hand — and this is certainly how Starbucks is putting it — encouraging people to vote seems unobjectionably patriotic. On the other hand, adhering to election laws is also a pretty good thing. (Starbucks has now retracted their offer, or rather they’ve expanded it to include voters & non-voters alike.)

On first blush, it’s hard to see how offering free coffee to anyone who votes could count as interfering with the election. After all, they weren’t offering free coffee to people who vote any particular way. That would be fine, in theory, if supporters of different parties were evenly distributed among patrons of different businesses. But they’re not. Businesses like Starbucks (and many others) tend to cater to particular demographics, and those demographic fault lines are politically important. For example, check out this factoid from NPR:

Of people who get their coffee at Starbucks, 52 percent favor Obama while 39 percent prefer McCain. Of people who frequent Wal-Mart, 58 percent favor McCain while 33 percent prefer Obama.

So, a company that knows its customers (and Starbucks surely does!) can have a partisan effect, even if it offers freebies to “all” voters.

Update:

Other companies offering similar promotions:

- Brighton: Independence from Taxes Day (requires proof of having voted) (I’ve emailed them to ask if they know they’re in contravention of elections laws)

- Krispy Kreme and Ben & Jerry’s are offering free stuff today, but aren’t specifically tying it to voting.

Another Update:

From Tim Storey’s blog: And the winner is…Starbucks!

I just voted at the venerable Wheat Ridge Presbyterian Church. After feeding my ballot into the tabulation machine, the wonderful pollworker handed me an “I voted” sticker and told me to be certain to go to Starbucks to get my free cup of coffee.

(Thanks Mindy!)

PhD Programs in Business Ethics

Here’s something for potential graduate students in Business Ethics. It’s a probably-incomplete list of PhD programs in Business Ethics.

Here’s something for potential graduate students in Business Ethics. It’s a probably-incomplete list of PhD programs in Business Ethics.

I often get email from students asking how to become a “business ethicist” or a “professor of business ethics.” There are several routes to one of those glorious destinations. The title “ethicist” is of course unregulated. Anyone can call themselves that, and some people claim the title without much justification. Getting to teach business ethics at a university requires a little more by way of credentials — usually a PhD focused on ethics (often through a philosophy department, but sometimes from a business school) or a PhD in a business field, or another doctoral-level degree such as a JD, paired with experience in ethics-related issues.

Anyway, for those of you who are students, or who are advising students, here’s a little list (in no particular order) that I’ve put together by informally polling folks on the Society for Business Ethics mailing list:

Ph.D. Programs Specializing in Business Ethics

Ph.D. Programs in Other Areas that Permit/Encourage a Focus on Business Ethics

- Penn State: Ph.D. in Business Administration – Management and Organization

- U of Washington’s Foster School of Business: PhD Program

- U of Virginia’s Darden School of Business: Doctoral Program

- U of Pittsburg’s Joseph M. Katz Graduate School of Business: PhD Program

- Loyola University Chicago: Philosophy PhD Program and Theology PhD Program

- Bentley University: Doctoral Degree Program

This list is of course radically incomplete. There are, for example, dozens of Philosophy PhD programs and Management PhD programs where you could do a dissertation on a topic in business ethics. I’ve only listed programs that were mentioned to me by colleagues as being especially interested in business ethics.

Please note: I’ve relied on information emailed to me in compiling this list. No endorsements are implied, and no warranties. Your mileage may vary, etc., etc.

Please feel free to contact me about serious errors or omissions.

Can Business (Ethically) Trust the FDA?

Some people take for granted that government regulators are watching over our safety with an eagle eye.

Some people take for granted that government regulators are watching over our safety with an eagle eye.

Others are skeptical, because they think regulatory agencies are either underfunded, or in the back pocket’s of industry.

Is it ethically OK for a company, in defending its own behaviour, to trust in, rely upon, and point to a regulatory decision?

Case in point: this story from the Washington Post: BPA Ruling Flawed, Panel Says

The Food and Drug Administration ignored scientific evidence and used flawed methods when it determined that a chemical widely used in baby bottles and in the lining of cans is not harmful, a scientific advisory panel has found.

In a highly critical report to be released today, the panel of scientists from government and academia said the FDA did not take into consideration scores of studies that have linked bisphenol A (BPA) to prostate cancer, diabetes and other health problems in animals when it completed a draft risk assessment of the chemical last month. The panel said the FDA didn’t use enough infant formula samples and didn’t adequately account for variations among the samples.

So, what are manufacturers to do now? The FDA says BPA is safe. But at least some reputable scientists think the FDA is wrong about that. Can companies go ahead, in good conscience, and use BPA in their products? On one hand, one might think it fair that companies be allowed to rely, ethically, on the advice of the top health-regulatory agency in the land. I mean, few things can be guaranteed, with 100% certainty, to be safe, but if the FDA’s word isn’t good enough, whose is? It’s not a rhetorical question. In writing about GM foods, I’ve said, look, not only do the FDA and Health Canada and the World Health Organization agree that GM foods are safe, but basically every reputable scientist in the world says so, too. But what about cases where there’s disagreement? Of course, it can’t be the case that just any scientific disagreement is sufficient to call a halt to production. How much is enough? In the case of BPA, I’m inclined to say that the FDA’s ruling makes it legal to use BPA, but ethically dubious. There is a very respectable sub-set of scientists who have grave reservations. That distinguishes this from the GM foods case. Of course, just what counts as “enough” scientific disagreement to tilt the landscape of ethical corporate behaviour is a big question. Any thoughts?

ImClone, Lilly, and the Interests of Shareholder

Here’s a good story about the (non)protection of shareholder interests, and the (non)homogeneity of shareholder interests.

From Forbes.com: Potential Roadblock For Imclone Deal.

Although it spent weeks teasing investors about the identity of its suitor, ImClone failed to satisfy all of its shareholders that a $6.5 billion bid from Eli Lilly fairly values the biotech business.

A pension plan, the State-Boston Retirement System, has filed a lawsuit in the New York State Supreme Court against the directors of ImClone … including its billionaire chairman, Carl Icahn, and against Eli Lilly … claiming that the biotech ‘s board failed to live up to its fiduciary duties when pursuing the offer and did not provide the necessary information to shareholders to make a proper decision.

The standard folk-view of the corporate world is that corporate boards are obsessed with pursuing the interests of shareholders — indeed, many people seem to think that the pursuit of profits for shareholders is the source of all corporate evil. Yet here’s a story where a group of shareholders feel like their interests are emphatically not being protected by the board.

Another standard element of the folk-view of the corporate world is that shareholders are a relatively homogenous group, all with roughly the same interests. Here, again, this story provides a counter-example. Icahn, chair of ImClone’s board, is also a very significant shareholder. (According to the WSJ, “Icahn owns 11.67 million shares of ImClone”.) Yet the shareholders represented by the SBRS seem to think their interests are not at all well lined up with his.

As always, the world is a somewhat more complicated place than is typically thought.

—

Thanks to Pharmalot.

Comments (1)

Comments (1)