Debating Capitalist Moral Decay

Is the collapse of capitalism upon us? Are we facing a moral armageddon in the marketplace? Is every scandal-driven headline another sign of impending apocalypse in the world of business? You could be forgiven for thinking so, if you read enough editorials.

Just look at the opinion pieces carried by major news outlets over the last month. Eduardo Porter editorialized in the NY Times about The Spreading Scourge of Corporate Corruption. The Atlantic carried a piece called The Libor Scandal and Capitalism’s Moral Decay, by Pulitzer Prize-winner David Rohde. Even business school professors are down with the effort to convince you that the end is nigh: Bloomberg just recently featured a piece by Prof. Luigi Zingales, who went to the apparent heart of the matter by asking, Do business schools incubate criminals?

But do editorials of that sort really bring to bear any solid evidence that things in the world of business are getting worse? Not as far as I can see.

I’ve argued before that the evidence for a real moral crisis in business is pretty scarce. Headlines don’t count as evidence. And pointing to the fact that people don’t trust business is putting the cart before the horse. People have been wringing their hands about moral decay and longing for the good ol’ days at least since the time of the ancient Greeks. So as far as I can see, things may not be all that bad. I’ve even argued that we are currently enjoying a sort of golden age of business ethics. Business today is, in may ways, more accountable and better behaved than ever before in history.

But I could be wrong about that. Really, who’s to say whether things are getting better or worse? It really depends an enormous amount on what you count as improvement, and how you measure it. So let’s call it a draw, and focus on what’s really important. The question isn’t whether moral standards in business are higher or lower than they were at some point in the past. The point is whether they’re currently high enough, and assuming the answer is “no,” what to do about it.

And there’s plenty of work to do. To begin, we need to keep working to find the right balance of regulatory carrots and sticks to encourage good corporate behaviour. And we need to figure out the right corporate governance policies and structures to foster good behaviour within corporations as well. And to the extent that bad behaviour in the corporate arena — as in literally every other area of life — is unavoidable, we need to think hard about the appropriate mechanisms to mitigate and remediate the effects of such behaviour. All of this requires a good deal of humility, of course, and a willingness to tolerate, even foster, a degree of creative experimentation.

But one thing is certain. Rather than wasting time worrying about whether the world is coming to an end, our energy would be better spent figuring out how to make it better.

Top 5 Business Ethics Movies

There are lots of ways you can learn about ethical issues in business. You can do some reading. You can take a course. But hey, it’s summer, so let’s talk movies. Here’s a list of my 5 favourite business ethics documentaries. Granted, these aren’t exactly great date movies. Nor are they action-packed blockbusters. But trust me you could do a lot worse.

So grab a bag of popcorn. Here they are, in no particular order:

Let’s start with one you’ve likely heard of, namely The Corporation (2003). This one was popular out of all proportion to either educational or entertainment quality. It’s full of half-truths and bizarre omissions. And its central theme, namely that the corporation is in some sense a psychopath, simply cannot withstand even cursory critical examination. But it’s still useful to watch — if only to understand the source and shape of so much anti-capitalist sentiment. (The Corporation is freely available online here.)

Next on my list is another what we might call ‘anti-business’ documentary, namely Walmart: The High Cost of Low Price (2005). This is one of my favourite videos for classroom use, because it’s a good test of students’ critical thinking skills. Some of the criticisms levelled at Walmart in the movie are entirely on-target: labour code violations, racist HR practices, etc. Other criticisms point to things that are in some sense sad, perhaps — the loss of so many mom-and-pop stores, for example — but far from evil. Others are downright ludicrous, such as blaming Walmart for random murders in their parking lots. Watching this one is a great way to see what is right, and what is wrong, with so many criticisms of business today.

The most recent of my top 5 is already a couple of years old. And while Food, Inc. isn’t about business per se, it is about the production of food, something that is increasingly industrialized and dominated by big business. And as businesses go, none could be more important to us than the food business. The movie does a good job of pointing out problems, but is regrettably short on solutions. A not-unrelated criticism is that the documentary makes too little use of relevant experts. How could a film make concrete recommendations about the future of food without bothering to interview, say, a food economist or two? At any rate, it’s a thought-provoking hour and a half.

Next on my list is a movie you probably haven’t heard of, namely The Take (2004). This one isn’t really a criticism of any particular company, or of any particular industry. At heart, it’s a plea for a different economic model — though the details here are a bit vague. The Take tells the true story of a group of Argentinian factory workers who, when their cruel capitalist boss shut down operations for obscure reasons, seize the factory, start up the machines, and try to make a go of it. The workers’ motto — “Occupy, Resist, Produce” — is in spirit awfully close to “Workers of the world, unite!” It’s a good story. Unfortunately, the movie ends before the story does. As the film closes, the workers have seized the factory and started up the machines and are full of optimism that they can do better without a boss. Can they really do it? Can they beat their little workers’ paradise beat the odds? The film leaves us with lots of idealistic hopes, but few answers.

My next recommendation is admittedly the dullest of the bunch, but still worth considering. A Decent Factory is a story about audits. Not financial audits, but supply-chain audits carried out by Nokia at the factories of one of its Chinese subcontractors. There are two striking aspects of this quiet film. The first is how the auditors seem to struggle with just how much to push their Chinese subcontractors on various issues. The auditors’ job is not an easy one. They are there to evaluate, but also to insist on improvements, or sometimes just to suggest, encourage, and cajole. The path forward is far from clear. This is related to the second striking aspect of the film, which is that the conditions at the Chinese factory are, well, mediocre. They’re not the kind of awful sweatshop that would make for a gripping exposé. Remember what your grade-school English teacher told you about the adjective “nice”? It’s a weak word, one that tells the reader little. That’s the sense in which the makers of this film use the word “decent” in their title. The Chinese factory is a…decent…factory. Not great. But not awful. And just what to think about that is left to the viewer.

Last but certainly not least is Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (2005). This one is arguably the best of the bunch. Based on the book by journalists Bethany McLean and Peter Elkind, the movie is a fun, accessible, and best of all plausible telling of the story of what is still the biggest and most complex business-ethics scandal of the century so far. Perhaps the thing that most attracts me to this documentary is its refusal to resort to easy answers. There’s no attempt to say it was “all about greed” or that “capitalism is evil.” The truth about Enron, and about capitalism more generally, is much more complex, and much more interesting, than that.

Ethics on Wall Street: Hate the Player, Not the Game!

A recent survey of Wall Street executives paints a bleak picture of the moral tone of a central part of our economic system.

According to the survey (conducted for Labaton Sucharow LLP), 24 percent of respondents believe that financial professionals need to engage in unethical behaviour in order to get ahead. 26 percent report having observed some form of wrongdoing, and 16 percent suggested that they would engage in insider trading if they thought they could get away with it.

Two points are worth making, here.

First, some perspective. Far from alarming, I think the number produced by this survey are relatively encouraging. Indeed, the numbers are so encouraging that I can’t help but suspect unethical attitudes and behaviours were seriously underreported by respondents. Only 26 percent had seen something unethical? Seriously? That seems unlikely. And the fact that only 16 percent said they would engage in insider trading is also relatively benign. There are, after all, people who believe that insider trading isn’t unethical at all, and shouldn’t be illegal. They argue that insider trading just helps make public information that shouldn’t be private in the first place. I don’t think that point of view hold water, but the fact that it’s put forward with a straight face makes it pretty unsurprising that a small handful of Wall Street types are going to cling to the notion.

Second, a survey like this highlights the difference between our ethical evaluation of capitalists, on one hand, and our ethical evaluation of capitalism, on the other. One of the major virtues of the capitalist system is that it is supposed to be able to produce good outcomes even if participants aren’t always squeaky clean. In no way does it assume that all the players will be of the highest virtue. Adam Smith himself took a pretty dim view of businessmen. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith wrote:

“People of the same trade seldom meet together, even for merriment and diversion, but the conversation ends in a conspiracy against the public.”

And yet despite his dim view of capitalists, Smith remained a great fan of capitalism — or rather (since the term “capitalism” hadn’t been coined yet) a fan of what he referred to as “a system of natural liberty.” The lesson here is that evidence (such as it is) of low moral standards on Wall Street shouldn’t make us panic. Perhaps it should make us shrug, and say, “Such is human nature.” The challenge is to devise systems that take the crooked timber of humanity and mould it in constructive ways. Governments need to take corporate motives as they are and devise regulations that encourage appropriate behaviour. And executives need to take the motives of their employees as they are and devise corporate structures — hierarchies, teams, incentive plans — that motivate those employees in constructive ways. In both cases, while the players should of course look inward at what motivates them, the rest of us should focus not on the players, but on the game.

The Hidden Ethical Value of Social Networking

Like it or not, we are in the middle of a social networking revolution. And of course, that’s hardly news. Endless ink, digital and otherwise, has been spent on worrying over whether Facebook, Twitter, and their rapidly-multiplying ilk are the best or the worst thing that has ever happened to humankind.

Like it or not, we are in the middle of a social networking revolution. And of course, that’s hardly news. Endless ink, digital and otherwise, has been spent on worrying over whether Facebook, Twitter, and their rapidly-multiplying ilk are the best or the worst thing that has ever happened to humankind.

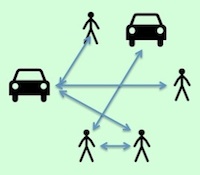

A recent story about car-pooling apps highlights the fact modern technology, including social media, has a role to play in making markets more efficient. And since efficient markets are generally a good thing, this counts as a big checkmark in the “plus” column of our calculations concerning the net benefit of social media.

Carpooling is a great example, because the relative lack of carpooling today is a clear instance of what economists call “market failure” — a situation in which markets fail efficiently to provide a mutually-beneficial outcome. Think of it this way. There are lots of people in need of a ride. And there are lots of people with rides to offer. The problem is a lack of information (who is going my way, at what time?) and lack of trust (is that guy a potential serial killer?) Social networking promises to resolve both of those problems, first by helping people coordinate and second by using various mechanisms to make sure that everyone participating is more or less trustworthy.

With regard to car-pooling, the obvious benefits are environmental. But the positive effect here is quite general: just about any time we find a way to foster mutually-advantageous market exchanges, we’ve done something unambiguously good. This is one example of the ethical power of social media.

Another big enemy of efficient markets is monopoly power, or more generally any situation in which a buyer or seller is able to exert “market power,” essentially a situation in which some market actor enjoys a relative lack of competition and hence has the ability to throw its weight around. Social media promises improvements here, too. Sites like Groupon.com allow individuals to aggregate in ways that give them substantial bargaining power.

The general lesson here is that markets thrive on information. Indeed, economists’ formal models for efficient markets assume that all participants have full knowledge — that is, they assume that lack of information will never be an issue. Social networks are providing increasingly sophisticated mechanisms for aggregating, sharing, and filtering information, including important information about what consumers want, about what companies have to offer, and so on. So while a lot of attention has been paid to the sense in which social media are “bringing us together,” the real payoff may lie in the way social media render markets more efficient.

5 Business Ethics Must-Reads

Business Ethics is an academic discipline, as well as a field of practical expertise and increasingly a central business function.

There are many ways to educate yourself about Business Ethics as a field of study and understanding. But if your interest in the topic is sufficiently deep, you could do worse than to read a handful of papers by some of the leading scholars in the field.

So here are five of what I regard as essential readings in business ethics, along with an explanation of their significance.

The List

In order to say anything useful about ethical issues in the marketplace, you first need to understand something about how markets work, how they fail, and what the ethical argument for their existence is. And simply being in business doesn’t guarantee that you understand markets, any more than being an athlete guarantees that you understand physiology. You need to go to someone who has a deep understanding just of one particular market — the market for mobile phones, say, or for cars — but of markets in general.

So the first bit of essential reading is a decent chunk of…

1. Adam Smith’s The Wealth of Nations. (It’s freely available online, and I recommend reading at least the first three chapters of Book 1, Volume 1.) Smith, one of the great philosophers of the Scottish Enlightenment, wasn’t the first to speculate about how economies work, but he’s generally thought of as the guy who more or less got it right. Smith is to economics what Darwin is to biology. In The Wealth of Nations, Smith outlines the basic way in which trade produces mutual advantages, the way those advantages encourage specialization, and — importantly — the way self-interest is sufficient to get the whole process started. (But a word of caution: Smith is often wrongly thought to have encouraged greed. Nothing could be further from the truth. For useful correctives, read Nobel-prizewinning economists Ronald Coase and Amartya Sen.)

#2. My next suggestion is to read something by Edward Freeman on what’s known in academic circles as “Stakeholder Theory.” His co-authored piece called “Stakeholder Capitalism” would do, as would any of a number of papers he’s authored or co-authored over the last 3 decades. The basic idea that Freeman defends is that corporate managers shouldn’t see themselves as beholden primarily to shareholders, but rather as ethically obligated to balance the interests of a wide range of stakeholders. The idea is attractive, but also deeply flawed, for reasons that the next two readings explain. One way or the other, the stakeholder idea forms an important part of the debate over how we should think about the central obligations of managers. (For my review of one of Freeman’s recent books on the notion, see here: Review of Managing for Stakeholders.)

#3. The best antidote to Stakeholder Theory is to read Joseph Heath’s “Business Ethics Without Stakeholders”. Heath argues that the stakeholder idea, however evocative, only muddies the water without providing managers with any useful direction. Heath’s paper basically outlines the fundamental debate over shareholders-vs-stakeholders in business ethics. In that regard, it’s a useful summary of the field. Heath argues that shareholder-driven and stakeholder-driven theories of business ethics both have virtues, but that both are also subject to fatal flaws. Heath argues for an alternative, which he calls the Market Failures theory. According to the Market Failures theory, the guiding ethical notions for businesses ought to be to honour the preconditions for market efficiency. In other words, they shouldn’t engage in the kinds of behaviours that make markets fail: they shouldn’t seek to profit from information asymmetries, or from externalities, or from exercising monopoly power.

#4. A bit of middle ground can be found in the work of John Boatright, including especially his article “What’s Wrong—and What’s Right—with Stakeholder Management”. In previous writings, Boatright has generally not been a fan of stakeholder theory. But in this paper, he says that the stakeholder idea can play a legitimate role in the corporation, if used properly. In particular, Boatright says that the stakeholder idea should only be held up as an ideal, a source of a sense of mission, a motivator reminding corporate insiders that all participants need to find long-term benefit. He says that the stakeholder idea is much less likely to serve the role that Freeman and his fans think it ought to play, namely that of a principle for corporate governance.

#5. All of the above is aimed at helping frame the question of how businesses (or people in business) ought to behave. But sometimes the problem isn’t with knowing the answer, but with putting it into action. And that seems to be a problem. After all, there’s a good deal of wrongdoing in the world of business. And yet look around you: most of the people you know (starting with yourself!) are pretty decent, honest folks. How do so many good people end up doing bad things.

In this regard, I have to recommend another paper by Joseph Heath, namely his “Business Ethics and Moral Motivation”. Heath points out that, when asked about what motivates wrongdoing, most people say it has a lot to do with greed, or with other deep character flaws. The trouble with this, he says, is that the scholars who study wrongdoing in the most depth — namely, criminologists — long ago considered and rejected those as key factors in wrongdoing. The real source of trouble, says Heath, lies in the ability people have to offer themselves excuses, and in particular to redescribe their behaviour their behaviour in ways that lets them rationalize it. “Sure, I took the money. But I wasn’t stealing — I was just taking what I was owed.” To get people to behave better, you need to help them see that such rationalizations are unsupportable, and we need to work to avoid institutional cultures that actually encourage thinking in those ways.

So that’s my list. It’s admittedly a particular take on the field — all of the authors cited above are philosophers. But hey, I’m a philosopher by training, and so I’m committed to the idea that an understanding of fundamental principles always helps. As someone once said, there’s nothing so practical as a good theory. Reading these won’t guarantee excellence in ethical decision-making, but they will help you understand what is fundamentally at stake in our ongoing exploration of what behaviour is right, and what behaviour is wrong, in the world of business.

A Business Ethics Syllabus

Here is a reading list that is typical of the one I use for my 1-term undergraduate Business Ethics courses. In some cases, there are hyperlinks directly to the work in question. In other cases, unfortunately, the link just leads to an abstract. Note that for the last decade, most of my teaching has been in a Philosophy department, and so this list includes more philosophical readings, and fewer case studies, than would be the case for a course at a business school.

Section 1: The Market

In order to say anything sensible about ethics in the marketplace, you need first to understand at least a bit about the marketplace itself, and the basic underlying mechanisms. So…

- Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations (Vol 1, Book 1, Ch. 1-3)

But a lot of people misunderstand Smith, especially his view on the role of self-interest in the marketplace. So I recommend reading these two Nobel-prizewinning economists, both of whom believe that Smith is far too important to get wrong:

- Ronald Coase, “Adam Smith’s View of Man” (Coase explores Smith’s moral psychology, and points out that Smith neither thought people are entirely selfish, nor thought they should be).

- Amartya Sen, “Does Business Ethics Make Economic Sense?” (Sen points out that, on Smith’s account, self interest merely explains what motivates people to engage in exchange. That’s important, but it leaves lots to be explained. And, Sen argues, much of what remains to be explained requires a richer set of values than the popular, cartoonish version of Smith usually includes.)

Section 2: For Whose Benefit?

In this section, we read about “stakeholder theory,” along with modifications of, and objections to, that idea.

- R. Edward Freeman, et al., “Stakeholder Capitalism” (In this and many other papers published over the last quarter century, Freeman defends the idea that corporate managers have strong, positive obligations not just to corporate shareholders, but to a wide range of stakeholders.)

- Kenneth Goodpaster, “Business Ethics and Stakeholder Analysis” (Goodpaster offers a friendly amendment to Freeman’s theory. He says we should understand stakeholder theory as implying that managers have strong fiduciary duties to shareholders, and regular non-fiduciary duties to other stakeholders — such as the duty not to lie, not to steal, etc.)

- John Boatright, “What’s Wrong—and What’s Right—with Stakeholder Management” (Boatright says that the stakeholder idea can play a legitimate role in the corporation, but only as a motivator, giving corporate insiders a sense of mission. He says that the stakeholder idea is unlikely to serve as a good principle for corporate governance.)

- Alexei M. Marcoux, “A Fiduciary Argument against Stakeholder Theory” (Marcoux argues that the relationship between corporate managers and their shareholders is in important ways very similar to that between doctors and their patients or lawyers and their clients. As a result, he says, shareholders — and shareholders alone — have a strong claim to managers’ loyalty as fiduciaries.)

- Joseph Heath, “Business Ethics Without Stakeholders” (Heath argues that shareholder-driven and stakeholder-driven theories of business ethics both have virtues, but that both also have fatal flaws. He argues for an alternative, which he calls the Market Failure theory, according to which the ethical compass of a corporation should be to avoid behaviours that tend rob the market of its promise as a mechanism for mutual benefit.)

Section 3: Decision-Making

The last section of the course deals with individual decision-making, and barriers to making good decisions.

- Aviva Geva, “A Typology of Moral Problems in Business” (Geva argues that not all problems in business ethica are of a single kind. She presents a framework for categorizing such problems, and argues that diagnosis is the first step towards effective resolution.)

- Caroline Whitbeck, “Ethics as Design: Doing Justice to Moral Problems” (Whitbeck says that ethics classes too often treat ethical dilemmas as if they were multiple-choice problems, in which the decision-maker merely needs to choose from the available alternatives. Instead, Whitbeck suggests that we think of ethics in a more active way as a design process, involving seeking a best available solution given a set of objectives and a range of constraints.)

- Joseph Heath, “Business Ethics and Moral Motivation: A Criminological Perspective” (Heath says that the “folk” theories regarding why people do bad things are generally deeply flawed, rejected long ago by thorough criminological studies. He says the key to wrongdoing is the process of rationalization or “neutralization,” according to which the wrongdoer finds ways of redescribing their own behaviour in order to soothe their own conscience.)

- Nina Mazar, On Amir, and Dan Ariely, “The Dishonesty of Honest People: A Theory of Self-Concept Maintenance” (Ariely and colleagues ask why it is that so many honest people engage in dishonesty. They propose a theory according to which people frequently find ways to be just a bit dishonest, but not so dishonest as to stop them from thinking of themselves as decent people.)

Here are a few other items I have sometimes included:

- The Corporation (this film is deeply flawed, but useful pedagogically)

- Allen Buchanan, “Toward a Theory of the Ethics of Bureaucratic Organizations” (Buchanan argues that the distinctive problem of bureaucratic organizations is the multi-layered agency problems that are endemic to them. He thus suggests that the distinctive ethics of such organizations must involve an attempt to inculcate norms that combat agency problems at all levels.)

- Michael E. Porter & Mark R. Kramer, “Strategy and Society: The Link Between Competitive Advantage and Corporate Social Responsibility” (A very sane, practical approach to CSR. Much better than their later work on “Creating Sustained Value.”)

- Ronald Coase, “The Nature of the Firm” (This is a ground-breaking paper by the Nobel-prizewinning economist. Coase argues that the existence of corporations — and the size of particular corporations — can be explained in terms of the need to minimize transaction costs.)

- Enron: The Smartest Guys in the Room (video) (This is a terrific documentary, avoiding the cheap-and-easy explanations for the biggest business scandal in recent decades. See my review here: Enron DVD)

It’s important to note what this list leaves out. Absent are direct discussion of workplace health and safety, honesty in advertising, product safety, environmental issues, and so on (though the readings above do of course draw examples from those sorts of topics). A different sort of course would deal with those, one by one, in some depth. The hope in my course is to provide students with the philosophical grounding to think about those sorts of practical issues in a well-informed way.

Obamacare and Business Values

Yesterday, the US Supreme court mostly upheld Obamacare, also known as the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act. (See the full decision here [PDF].)

The Big Decision may have been made, but clearly lots remains to be sorted out. One of the questions that arises, from an ethical point of view, is the way that businesses, including especially insurance companies, should conduct themselves under the new plan.

Under Obamacare, Americans will be required to carry health insurance (or face a penalty) and, importantly, insurance companies will be required to sell policies to all comers, regardless of pre-existing health conditions. While the debate has focused primarily on the proper role of government, the Patient Protection and Affordable Care Act clearly has significant implications for private companies.

Note how different this is from, for example, Canada’s system. In Canada, insurance is provided by provincial health plans, and care is provided by physicians (as private contractors) and private, not-for-profit hospitals. Private insurers still play a role in pharmaceutical coverage, but almost no role at all in basic healthcare. Under Obamacare, in comparison, insurance companies effectively become an instrument of public policy: important elements of the way they conduct their business (and in particular the actuarial rules they apply) will no longer be up to them. This is far from the only example of private companies playing a role in public insurance: in the UK, private companies play a significant role in administering employment insurance services, and in some Canadian provinces private insurance brokers sell auto insurance plans underwritten by a public insurer. With regard to insurance, the distinction between private and public is far from water-tight.

How should companies conduct themselves when they play a role in delivering publicly-mandated insurance? Should they continue to think of themselves entirely as private, profit-seeking entities? Or should they — like industrial firms during times of war — take up public values?

Just what values are instantiated in a public insurance scheme is a matter of some debate. Public insurance schemes are often seen as promoting egalitarian values — ‘we’re all equal and hence all deserve equal access to basic healthcare.’ Others argue that what’s really at stake in such schemes is not equality, but efficiency (and argue that the current patchwork American system, for example, is quite inefficient in a number of ways). Others argue that, for insurance quite generally, solidarity is the key value — and one with obvious salience when insurance is part of the welfare state. Of course, to the extent that insurance companies are “merely” private corporations, they are guided by basic norms related to loyally seeking profits for shareholders. But even private insurance companies are subject to special limits on their profit-seeking. From a legal point of view, it is recognized that insurance companies are morally special: the legal principle of uberrima fides implies that the level of trust required between insurer and insured makes the relationship special, from an ethical point of view. And then, with regard to mutuals and not-for-profit insurers, stewardship of a shared resource (i.e., the insurance fund upon which members rely) is a key value. It seems right that private and public insurers would be guided by different mixes of these values.

So the question American health insurance companies face, at least in principle, is whether they should conduct themselves like private or public entities. And the question Americans face is which standard to hold them to. The answer, I think, is not clear. But it’s worth pointing out that the goals of an institution — public or private — don’t automatically have to be the goals of the larger system of which it is part. As I’ve pointed out elsewhere, the individual parts of a system don’t need to act according to the values of that system — sometimes they contribute by playing a more narrow role.

The coming years are sure to see significant changes in the US insurance industry. Whether the US government can succeed in getting private insurers to play a public-policy role remains to be seen, and depends in part on the willingness of those insurers to take up a public mission. But it depends just as much on whether the system Obama has designed is capable of harnessing the profit motive of insurance companies using it to get them to perform an important social function.

Flexibility in the Workplace?

What kind of workplace do you want? Should your workplace experience be determined by regulations, or instead be negotiated between you and your employer?

A recent survey sheds interesting light on what people love, and hate, about their workplaces. They survey, carried out by Wakefield Research for Citrix, produced lots of interesting tidbits. For example, among male workers, the part of office life they secretly hate most is office baby showers. 32 percent of workers would give up their lunch breaks in exchange for the chance to work at home just one day per week. Oh, and 7% of workers, when given the chance to work from home, prefer to work in their underwear or in the nude. And so on.

Citrix is an internet and cloud computing company, so naturally the take-away lesson they suggest has to do with the advantages of telecommuting, and in particular with the desirability of employers offering employees the flexibility to work, at least occasionally, from home.

But the question of flexibility arises at more that one level. It arises at the level of what employers offer employees — will they offer employees the flexibility to work from home occasionally if they choose? It also arises at the level of employers: should employers have the option to either offer such flexibility or not, or should all employers be required to offer the same kinds of flexibility? In other words, should there be a firm rule (entrenched in either law or regulation) requiring employers to offer such options?

More generally, what elements of work life ought to be regulated to the point of being standardized? And which elements ought to be up to employers and employees to sort out? The generic argument for uniformity is reasonably clear: people are people, and ought generally to be treated in similar ways regardless of where they work.

But there are also arguments for diversity in employment arrangements. Most obviously, there’s an argument based in the importance of freedom of choice. Why should everyone be forced to work under one set of circumstances? Shouldn’t the terms of the employment contract be a matter of free negotiation — within broad limits, perhaps defined in terms of fundamental human rights — between employer and employee?

But customization of workplace experience also holds the promise of better outcomes, at least in theory, because different workers likely want and value different things in a workplace. And there will always be tradeoffs. Some may prefer a workplace that rewards long hours with high pay. Others may prefer “good” pay in return for “reasonable” hours. Some may want to work in a close-knit team that works and plays together, while another may prefer a strict separation of work and pleasure. In this sense, a workplace is a product like any other, one that we “buy” with our labour. And, as with food or anything else, different people will want different things. If you can find ways to give more people what they want, you’ve done a good thing.

I find this a useful way of framing questions related to employment standards. For any given question, we should ask: is this something that we need to legislate into regularity, or something on which we need to allow diversity? If the former, then we’re faced with the hard challenge of figuring out what the single best standard is for all to follow. If the latter, then the challenge is to figure out how to make sure that the choices employees make are free and informed.

How can we decide which category a particular workplace issue falls into? That’s the hard part. It’s tempting, philosophically, to say that we just need to figure out whether the issue at hand is an issue with regard to which rational argumentation seems to lead to a single solution. But whether a single, clear answer is available is itself something over which people can disagree. Closer to the truth is that what we need to do is figure out whether the gains made by enforcing regularity are sufficient to outweigh the positive outcomes that come from a tailored workplace experience.

Sandusky’s Lawyer & Business Ethics

Just like a defence lawyer in a criminal trial, a CEO has a specific goal to achieve. The CEO’s goal is to turn a profit, and it’s a goal rooted as much a duty to society as it is a duty to shareholders. And, importantly, when it comes to both defence lawyers and CEOs, you don’t have to agree with their goals in order to value the role they play in the larger system.

The trial of former football coach Jerry Sandusky illustrates what I’m talking about.

Jerry Sandusky’s lawyer has an unenviable job. His job is to defend—vigorously and wholeheartedly—a man that pretty much everyone else has already assumed is guilty.

Joseph Amendola, lead defence lawyer for Sandusky, has taken on the task of defending the former Pennsylvania State University assistant football coach against 52 charges of child sexual abuse. In the minds of many, this makes Amendola only slightly less worthy of scorn than his client. After all, how can anyone seriously defend a man against whom there is so much compelling evidence?

The catch here is that we cannot evaluate the ethics of a defence lawyer without looking at the bigger picture, and the bigger picture is the adversarial system within which the defence lawyer operates. Amendola isn’t just some guy defending a child molester; he’s a defence attorney playing his part in a system that places very specific ethical obligations on defence attorneys.

The point here isn’t really about the legal system. The point is that the people who play a role in a system don’t necessarily have to pursue the goals of the system directly. In fact, in some cases that would be downright counter-productive. Let’s assume, for example, that the goal of the criminal justice system is precisely what the name implies: justice. The fact that justice is the goal of the system absolutely doesn’t imply that every participant in the system has to pursue justice. Compare: a football team’s objective is to get the football into the opponent’s end-zone. But that doesn’t mean that every member of the team is trying to get the ball across that line. An Offensive Guard who focused on moving the ball would be failing at his job: his job is, pure and simple, to protect the quarterback.

What’s important in any complex institution—football team, system of justice, or a market — is that every ‘player’ do his part. Then if the institution is designed reasonably well, the sum total of the actions of various ‘players’ will result in the system that performs well as a whole. If all the players on a football team do their jobs well, the ball moves forward toward the end zone. If all the lawyers in a system of criminal justice do their jobs well, then more often than not the guilty will be punished and the innocent will go free.

So, Amendola is duty-bound to make Sandusky’s interests his first priority. But the reason is not that Sandusky deserves it. The reason is that the system as a whole requires it. The adversarial legal system can only have any hope of rendering justice if the parts of the system diligently play their roles.

The exact same principle applies to the profit-seeking behaviour of CEOs. As Joseph Heath points out in his scholarly work on this topic, the profit-seeking behaviour of companies is an essential element of the pricing function of the Market. When companies pursue profits in a competitive environment, it helps drive prices toward market-clearing levels. This helps ensure that supply of and demand for a given product settle at the socially-optimal level. So it is important, not just to shareholders but to society as a whole, that companies pursue profits. That is how companies and their CEOs play their role in producing the social benefits that flow from the market.

Of course, in the case of both defence lawyers and corporate executives, the obligation to pursue partisan goals is not unlimited. There are certain things you cannot do as a defence lawyer—suborning perjury, for example, or tampering with evidence. Such behaviour would reliably subvert the goals of the system. Similarly, there are things that an executive must not do in pursuit of profits. Figuring out which things those are—what the limits are on competitive behaviour in an adversarial market—is the very heart of business ethics.

Organic Foods and Bad Behaviour

Is labelling foods as “organic” a positive thing or not? The Environmental Working Group certainly thinks so. To support this notion, the EWG has just released its annual “dirty dozen” list, consisting of fruits and veggies that are especially high in pesticide residue.

But check out this recent study, which suggests that seeing and thinking about organic foods can make people less ethical. The researchers report that test subjects asked to look at and rank (basically, to focus on) either a bunch of organic-labelled foods or to look at and rank either comfort foods (e.g., ice cream) or a more neutral food (e.g., mustard). Following this, the test subjects were given tests to evaluate a) their willingness to help a needy stranger, and b) the harshness of their evaluation of various apparent moral transgressions. The result: people exposed to organic foods were both less likely to help others, and more likely to be harshly moralistic.

This is an interesting result in its own right, but it has particular implications for marketing. Very roughly, the study suggests that marketing produce as organic can have negative effects on consumers’ attitudes and behaviour. That is, the study says nothing negative about organic food itself, or about consuming it. The implication is specifically for labelling it and promoting it as organic.

Of course, we can’t immediately condemn such marketing based on this kind of evidence. It may well be that the net effect of selling lots of organic food outweighs the effect such marketing has on people’s attitudes and behaviour. But at very least, this should make us stop and think.

Now, it’s highly unlikely that this effect is specific to organic foods. Presumably, labelling food as organic here is relevant because for many people that label implies something virtuous. So the implication is that promoting foods (or presumably other products) in terms of virtue could be a mistake.

In general, labels that indicate a product’s characteristics help consumers get what they’re looking for. This is especially important with regard to characteristics that can’t be seen with the naked eye, including key characteristics of most so-called ethical products. You can’t tell by looking at an apple, for instance, whether it’s been sprayed with pesticides — unless, of course, you see the “Certified Organic” label on it. Labels of various kinds help people get what they value, and in that way help achieve the promise of a free market.

The alternative to using labels to help people find products that match their own values is to rely on government regulation and industry “best practices.” If there were widespread agreement that organic foods really were better, ethically, they there would be some justification for having government use legislation to drive non-organic foods from the market. We rely on labels and third-party certifications precisely because there isn’t sufficient consensus to warrant a general standard. But the study described above highlights one of the costs of the path we’ve chosen. By moralizing the marketplace we may, ironically enough, be encouraging immoral behaviour.

—–

Thanks to Andrew Potter for pointing me to the study discussed here.

Comments (8)

Comments (8)