Archive for the ‘activism’ Category

Greenpeace, Tar Sands and “Fighting Fire With Fire”

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

See this item, by Kevin Libin, writing for National Post: Yogourt fuels oil-sands war.

Here’s what is apparently intolerable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement that compares the consistency of tailings ponds to yogourt.

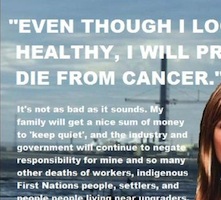

Here’s what is evidently acceptable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement warning that a young biologist working for Devon Energy named Megan Blampin will “probably die from cancer” from her work, and that her family will be paid hush money to keep silent about it….

It’s worth reading the rest of the story to get the details. Basically, the question is about the standards that apply to advertising by nonprofit or activist groups like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace. But it’s also more specifically about whether it’s OK for such groups to get personal by including in their ads individual employees of the companies they are targeting.

A few quick points:

- Many people think companies deserve few or no protections against attacks. Some people, for example, think companies should not even be able to sue for slander or libel. Likewise, corporations (and other organizations) do not enjoy the same regulatory protections and ethical standards that protect individual humans when they are the subjects of university-based research. Corporations may have, of necessity, certain legal rights, but not the same list (and not as extensive a list) as the list of rights enjoyed by human persons. So people are bound to react differently when activist groups attack (or at least name) individual human persons, as opposed to “merely” attacking corporations.

- Complicating matters is the fact that the original ads (by Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, or CAPP) themselves featured those same individual employees. So the employees had presumably already volunteered to be put in the spotlight. But of course, they volunteered to be put in the spotlight in a particular way.

- For many people, the goals of the organizations in question will matter. So the fact that Greenpeace and the Sierra Club are trying literally to save the world (rather than aiming at something more base, like filthy lucre) might be taken as earning them a little slack. In other words, some will say that the ends justify the means. On the other hand, the particular near-term goals of those organizations are not shared by everyone. And not everyone thinks that alternative goals (like making a profit, or like keeping Canadians from freezing to death in winter) are all that bad.

- Others might say that, being organizations explicitly committed to doing good, Greenpeace and the Sierra Club ought to be entirely squeaky-clean. If they can’t be expected to keep their noses clean, who can? On the other hand, some might find that just a bit precious. Getting the job done is what matters, and it’s not clear that an organization with noble goals wins many extra points for conducting itself in a saintly manner along the way.

(I’ve blogged about the tar sands and accusations of greenwashing, here: Greenwashing the Tar Sands.)

—

Thanks to LW for sending me this story.

WikiLeaks and NGO Legitimacy

The ethical standards that apply to an organization depend in part on what kind of organization it is. Some standards are either universal or nearly so: lying, cheating, stealing are generally bad whoever you are. But lots of other rules, principles, and values will vary, at least in terms of the weight attached to them. It matters for lots of purposes whether you are a corporation, a government agency, a non-governmental organization (NGO), a social club, a church, or a newspaper.

What kind of organization is WikiLeaks? It is sometimes referred to as a news agency, though that designation is disputed. Let’s look at WikiLeaks as a straightforward cause-oriented NGO, for the sake of argument.

One key question we ought to ask with regard to any NGO has to do with its legitimacy. In other words, for any NGO, we need to ask, “does this group have the right to speak and act on behalf of the cause it claims to speak and act for?” In other words, anyone may claim (for example) to “represent the forces of Good” or to “stand for justice” or to “speak for the whales.” And anyone is free to say what they want in defence of goodness or justice or whales. But saying you speak for goodness or justice or whales doesn’t mean that you actually do, and it doesn’t mean that anyone should listen to you or consult you on important decisions. Being a legitimate spokesperson takes something else. But what?

One framework that I’ve found useful is the one provided by Iain Atack in his paper “Four Criteria of Development NGO Legitimacy.”1. Atack’s framework is intended to apply to development NGOs, but I think that the basic idea can be applied more broadly.

Atack suggests that an NGO may gain legitimacy from one or more of 4 sources:

- Representativeness (Does the organization, for example, have a large membership base for which it genuinely speaks?)

- Effectiveness (Does the organization have a proven track record of getting the job done?)

- Empowerment (Does the organization work not just to achieve its goals, but to make sure that those it helps are, in the long run, left better-able to achieve those goals themselves?)

- Values (Does the organization embody and promote the values that are essential to the sort of organization it is, whatever those may be?)

Each of these is a way in which an NGO might acquire legitimacy. Some NGOs might score well on several of those. Some on just one. Some on none — and those that score well on none of those criteria are, according to Atack’s framework, lacking in legitimacy. Stated negatively, we could put the point this way: if an organization doesn’t have a membership base, isn’t effective, doesn’t work to empower those it seeks to help, and doesn’t embody the relevant values, then just what makes it think it has the right to speak or act for anyone other than itself?

Of course, these are not all-or-nothing questions. An organization can be representative, effective, etc., to a greater or lesser degree, and hence be either more or less legitimate.

This framework isn’t the be-all and end-all of assessing NGO legitimacy, but it’s a starting point. So, consider an NGO like WikiLeaks. Where does its legitimacy come from? In other words, what is the source of whatever moral authority is has? Is it from one of the sources Atack suggests, or is it something else?

—–

1Ian Atack, “Four Criteria of Development NGO Legitimacy,” World Development, 27:5 (1999) 855-864.

Wikileaks, Credit-Card Companies, and Complicity

I was interviewed last night on CBC TV’s “The Lang & O’Leary Exchange” about Mastercard and Visa’s decision to stop acting as a conduit for donations to the controversial secret-busting website Wikileaks. [Here’s the show. I’m at about 15:45.] (For those of you who don’t already know the story, here’s The Guardian‘s version, which focuses on retaliation against Mastercard by some of Wikileaks’ fans: Operation Payback cripples MasterCard site in revenge for WikiLeaks ban. )

I was interviewed last night on CBC TV’s “The Lang & O’Leary Exchange” about Mastercard and Visa’s decision to stop acting as a conduit for donations to the controversial secret-busting website Wikileaks. [Here’s the show. I’m at about 15:45.] (For those of you who don’t already know the story, here’s The Guardian‘s version, which focuses on retaliation against Mastercard by some of Wikileaks’ fans: Operation Payback cripples MasterCard site in revenge for WikiLeaks ban. )

Basically, the show’s hosts wanted to talk about whether a company like Mastercard or Visa is justified in cutting off Wikileaks, and essentially taking a stand on an ethical issue like this.

Here’s my take on the issue, parts of which I tried to express on L&O. Now just to be clear, what follows is not intended to convince you whether you should be pro- or anti-Wikileaks. The question is specifically whether Mastercard and Visa, knowing what they know and valuing what they value, should support Wikileaks’s activities.

I think that, yes, Mastercard & Visa are justified in cutting off Wikileaks. And I don’t think that conclusion depends on arriving at a final conclusion about the ethics of Wikileaks itself. The jury is still out on whether the net effect of Wikileaks’ leaks will be positive or negative. Likewise it is still unclear whether Wikileaks’ activities are legal or not. And who knows? History may be kind to Wikileaks and its front-man, Julian Assange. The question is whether, knowing what we know now, it is reasonable for Mastercard & Visa to choose to dissociate themselves. I think the answer is clearly “yes.” The key here is entitlement: the secrets that Wikileaks is disclosing are not theirs to disclose. They don’t have any clear legal or moral authority to do so, and so Mastercard & Visa are very well-justified in declaring themselves unwilling to aid in the endeavour.

One question that came up in last night’s interview had to do with complicity. Is a company like Mastercard or Visa complicit in the activities of Wikileaks? The answer to that question is essential to answering the question of whether the credit card companies might have been justified in simply claiming to be neutral, neither endorsing nor condemning Wikileaks but merely acting as a financial conduit. I think the answer to that question depends on at least 3 factors.

- 1. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa actually endorse Wikileaks’ activities?

- 2. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa know about those activities? and

- 3. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa actually make Wikileaks’ activities possible? That is, what is the extent of their causal contribution? Do they play an essential role, or are they a bit player?

In terms of question #1, it’s worth noting the significance of the particular values at stake, here. Wikileaks stands for transparency and for publicizing confidential information. Visa and Mastercard stand for pretty much the exact opposite. Visa and Mastercard, like other financial institutions, are able to do business because so many people trust them with their financial and other personal information. And so the credit card companies are, of all the companies you can think of, pretty clearly among the least likely to be able to endorse Wikileaks’ tactics, whatever they think of the organization’s objectives.

It’s also worth noting the significance of the notion of “corporate citizenship,” here. That term is widely abused — sometimes it’s used to refer to any and all social responsibilities, broadly understood. But if we take the “citizenship” part of “corporate citizenship” seriously, then companies need to think seriously about what obligations they have as corporate citizens, which has to have something to do with their obligations vis-a-vis government. Regardless of how this mess all turns out, the charges currently being bandied about include things like “treason” and “espionage” and “threat to national security.” These are things that no good corporate citizen can take lightly.

Spoof Chevron Ad Campaign: Too Dumb to be True

Earlier this evening, I briefly posted a blog entry about a too-dumb-to-be-true ad campaign, supposedly by Chevron. The spoof ad campaign made Chevron look very dumb. And say what you will about the oil giant: it ain’t dumb.

I won’t say who is (apparently) behind the spoof, because a) that’s exactly the kind of publicity this stunt was intended to generate, and b) from what I can tell (from this and previous stunds) this gang is only good at media manipulation, and does nothing to promote smart solutions.

Tomorrow, I’ll post about the real Chevron ad campaign. (And yes, the image above is real, from the Chevron “We Agree” website.)

Comments (4)

Comments (4)