Archive for the ‘finance’ Category

CEO Pay for Performance in Canada

CEO pay — in Canada, at least — is apparently more closely aligned with corporate performance than most people have suspected.

Last week I had the pleasure of hosting Matt Fullbrook, Manager of the Clarkson Centre for Business Ethics and Board Effectiveness, as part of my Business Ethics Speakers Series. Fullbrook’s presentation focused on an interesting study recently completed by the Clarkson Centre.

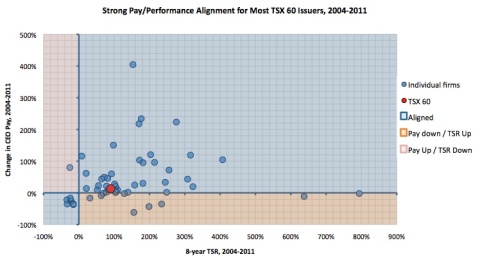

Much of the discussion focused on this provocative graph:

The graph plots change in CEO pay against total shareholder return (TRS). Each dot represents a company listed on the TSX 60. The red dot shows the average for all companies studied. The blue shaded areas indicate companies at which CEO pay and shareholder value have been headed in the same direction (up or down) over the 8 years under study (2004-2011). The other areas show misalignment. The vast majority of companies are in the blue regions. Only at one company did pay rise substantially without a commensurate rise in shareholder value, and several companies showed phenomenal growth in value with no change in CEO compensation.

After his presentation, Fullbrook summarized the study’s findings for me this way: “Our research shows that CEO pay and performance are largely in sync at Canada’s largest corporations, contrary to conventional wisdom. Despite the Financial Crisis, and a significant amount of CEO turnover, most issuers have successfully aligned executive compensation with shareholder returns, which is great news for investors.”

I’ll leave you with just a couple of comments on this.

First, it’s worth noting that the x-axis on the graph above shows change in CEO pay, rather than absolute level of CEO pay. So while we can see that not many Canadian companies provided their CEOs with big raises, that doesn’t mean that they weren’t overpaid to start with. They may or may not have been; that’s a different study. But the fact that pay and performance are heading in the same direction is still pretty significant, given that lots of criticism has been rooted in the perception that CEO pay was climbing while investors get shafted. This study shows that, in general, that’s not true in Canada.

Second, just what counts as “alignment” is itself a difficult question, and during his presentation Fullbrook was thoughtful in this regard. What we see in the red dot in the graph above is a kind of correlation. It suggests that the pattern in Canada is that a slight upward trend in CEO pay is accompanied by a bigger upward trend in shareholder value. But this leaves open questions such as whether TRS is the right measure of “performance” (even if we focus exclusively on the interests of shareholders).

And if we try looking at individual companies, at a particular moment in time, the question of alignment becomes even more difficult. The word “alignment” itself arguably suggests parallel trajectories. But where a CEO is overpaid, it makes sense for pay to go down even while (hopefully) value is going up. The attempt there is to make pay commensurate with value, not to push them in the same direction.

Executive compensation continues to be one of the hardest problems faced by corporate boards, as well as an absolutely key ethical obligation. Doing it well is difficult when we’re not even sure what doing it well looks like.

Ethics of Risk Management

Business is, in many ways, all about risk. It’s about investing in R&D and in productive processes that may or may not result in products that customers want to buy. It’s about hiring people and then putting your company’s reputation into their hands. It’s about trying and doing new things, always aware of the chance of failure. Society flourishes because businesses are willing to take risks. Of course, some risks should not be taken, and others should be taken only subject to suitable safeguards. Risk, in other words, needs to be managed.

Modern risk management, as that term is used in corporate contexts, has its roots in finance and refers primarily to the management of financial risks. It relies heavily on mathematical models used for asset pricing and portfolio assessment. Banks use risk management techniques to determine how many loans and mortgages of what kinds to hand out, and on what terms, and to figure out (within regulated limits) how much capital they need to keep on hand in case depositors come calling to reclaim their deposits. This all requires careful calculations. Take too little risk, and you’ve got money sitting idle. Take too many risks and, well, you end up with what we saw back in 2008.

Last week I had the pleasure of hosting Professor John Boatright, as part of the Business Ethics Speakers Series that I run at the Ted Rogers School of Management. John is the guy who literally wrote the book on ethics in finance. He’s author of Ethics in Finance and editor of Finance Ethics: Critical Issues in Theory and Practice. There simply is no one better on issues of ethics in finance. And his topic last week was an important one: “The Ethics of Risk Management: A Post-Crisis Perspective.”

As John’s talk pointed out, the advent of modern risk management strategies is, somewhat ironically, implicated in the financial crisis of ’08-’09, from which we are still recovering. The mathematical models risk managers use made possible the popularization of collateralized debt obligations (CDOs) and credit default swaps (CDSs). And the fact that there were actual hard-core equations behind these instruments — which Warren Buffett “financial weapons of mass destruction” — made them seem far safer than they were. This illusion of safety encouraged very high levels of leveraging, with what we now know to be disastrous consequences.

One of the other things that John’s talk clarified for me was that there’s a kind of ambiguity in the very term “risk management.” To the public, the idea of “managing” risks sounds very much like the idea of “reducing” risks. And that, of course, sounds like a very good thing. But risk management absolutely is not the same as risk reduction. Indeed, it can be quite the opposite. Risk management is the art of finding the right level and mix of risks, the right ‘risk profile.’ What matters ethically, as John pointed out is which risks are managed, by whom, by what means, for whose benefit.

The other point from John’s talk that I want to highlight here has to do with the ‘corporatization’ of risk management. As John pointed out, business firms both encounter and create risk, and risks are encountered by both firms and by individuals in society. If, as seems to be the case, risks to individuals are increasingly being managed by corporations, we as a society need to be acutely aware of the way corporations think about risk. John quoted author Michael Power as saying that “Risk is the basis for corporations to process morality.” In other words, risk is the lens through which corporations consider and act upon their obligations.

The problem here is clear: risk is an inherently outcomes-based construct, and not everything we care about ethically is a matter of outcomes. We also care about rights and duties, and about justice in the way good and bad outcomes are distributed. If risk becomes the lens through which obligations are examined, something important is being left out. Corporate risk management, in other words, is itself a mechanism that brings risks that need to be managed.

Should JPMorgan Fire the London Whale?

Would you fire an employee responsible for losing your company a couple billion dollars? I mean, hey, mistakes happen. But we’re talking two billion, here, with a “B”.

It’s not a hypothetical question, at least not for one major financial institution. As has been widely reported, JP Morgan Chase has now acknowledged that recent trading losses of two billion dollars are “somewhat related” to the controversial activities of a single London-based broker. The broker, whose real name is Bruno Iksil but who is often referred to as The London Whale, made enormous bets on U.S. corporate bonds…and lost.

I don’t think anyone has seriously suggested firing The Whale, at least not in public. But it does make you wonder. Even a company the size of JPMorgan can’t quite shrug off losses of that magnitude. And as others have pointed out, the hit to the company’s reputation may be more damaging, in the long run, than the short-run hit to its bottom line.

It’s worth noting that The London Whale was not a rogue trader. Indeed, his strategy was widely known, and apparently approved of by top executives at the company’s chief investment office.

Still, executive approval or no, it would be easy enough to make a scapegoat of The London Whale. But of course, that would be disingenuous, and the complicity of the Whale’s bosses is now public knowledge. And anyway, it’s entirely possible that the company will continue to see him as a valuable trader. He lost money this time around, but only insiders have the numbers to know how much he has made or lost for the company during his years there. And it’s entirely possible for even a losing bet to be regarded as one that it was smart to make in the first place.

There is also a public interest angle here. One of the key lessons of the last 4 years has been that innovative risk-taking by financial institutions can be a threat to the public good, not to mention the public purse. So even if The London Whale, and his overseers, aren’t destined to be axed by those who serve the company’s shareholders, that doesn’t mean they don’t collectively deserve our opprobrium, in addition to warranting stricter regulation.

Financial Advice, Competency, and Consent

I blogged recently on a California case about an insurance agent who was sentenced to jail for selling an Indexed Annuity — a complex investment instrument — to an elderly woman who may have been showing signs of dementia. I argued that giving investment advice is just the sort of situation in which we should expect professionals to live up the standard of ‘fiduciary’, or trust-based duty. An investment advisor is not — cannot be — just a salesperson.

But asserting that investment advisors have fiduciary duties doesn’t settle all relevant ethical questions. It settles how strong or how extensive the advisor’s obligation is; but it doesn’t settle just how the financial advisor should go about living up to it.

The story alluded to above again serves as a good example of that complexity. How should a financial advisor, in his or her role as fiduciary, handle a situation in which the client shows signs of a lack of decision-making competency? Sure, the advisor needs to give good advice, but in the end the decision is still the client’s. How can an advisor know whether a client is competent to make such a decision?

In the field of healthcare ethics, there is an enormous literature on the question of ‘informed consent,’ including the conditions under which consent may not be fully valid, and the steps health professionals should take to safeguard the interests of patients in such cases.

The way the concept is explained in the world of healthcare ethics, informed consent has three components, namely disclosure, capacity and voluntariness. Before a health professional can treat you, he or she needs to disclose the relevant facts to you, make sure you have the mental and emotional capacity to make a decision, and then make sure your decision is voluntary and uncoerced. And the onus is on the professional to ensure that those three conditions are met. But there’s really nothing very special about healthcare in this regard. Selling someone an Indexed Annuity isn’t as invasive, perhaps, as sticking a needle in them, but it often has much more serious implications.

Of the three conditions cited above — disclosure, capacity and voluntariness — disclosure is of course the easiest for those in the investment professions to agree to. Of course you need to tell your client the risks and benefits of the product you’re suggesting to them. But of course, many financial products have an enormous range of obscure and relatively small risks — must the client be told about those, too? There’s only so much time in a day, and most clients won’t care about — or be able to evaluate — those tiny details.

Voluntariness might also be thought of as pretty straightforward. A client who shows up alone and who doesn’t seem distressed is probably acting voluntarily, and it’s unlikely that we want investment professionals poking around our personal lives to find out if there’s a greedy nephew lurking in the background and badgering Aunt Florence to invest in penny stocks.

What about capacity? That’s the tough one, the one implicated in the court decision alluded to above. Notice that in most areas of the market, no one tries to assess your capacity before selling to you. I bought a car recently, and all the salesperson cared about was a driver’s licence and my ability to pay. No one tried very hard to figure out if I was of sound mind — beyond immediate appearances — and hence able to make a rational purchase.

Investment professionals do typically recognize a duty to ensure the “suitability” of an investment, and presumably whether an investment is suitable depends on more than just the client’s financial status. It also depends in part upon whether the client is capable of understanding the relevant risks. Being a true professional and earning the social respect that goes with that designation is going to require that financial advisors of all sorts adopt a fiduciary view of their role. That means learning at least a bit about the signs of dementia and other forms of diminished capacity. It also means knowing how and when to refer a client to a relevant health professional. Finally and most crucially, it means putting the client first — solidly and entirely first — and hence being willing to forego a sale when that is clearly the right thing to do.

Investment Advice and Fiduciary Duties

Most of us rely on accredited professionals for a range of services. Doctors, lawyers, accountants and so on play a huge role in our lives, giving us advice and rendering services that we would be foolish to provide for ourselves. Some topics, in other words, are beyond the ken of even the dedicated do-it-yourselfer. Financial planning is in that category. If you plan to do anything much beyond storing your money in a mattress, you probably want help from a professional. And you hope — really, really hope — that that professional is on the ball and has your best interests at heart.

A recent story highlights some of the difficulties in this regard. The story is about an independent insurance agent facing jail time for selling a particular kind of investment — an indexed annuity — to an 83-year-old woman. The catch: prosecutors say the woman showed signs of dementia, and the implication is that the agent took advantage of the fact that the buyer may not have understood the limits and disadvantages of the investment instrument she was buying.

Even minus the question of the buyer’s competency, there are worries here. For perspective on this story, I talked to Prof. John Boatright, who literally wrote the book on ethics in finance. He pointed out to me that Equity-Indexed Annuities are so complex that they’re a dubious product quite generally. He also pointed out that such annuities are investment instruments sold by people in the insurance industry who are not truly investment specialists. Most investment instruments are regulated such that they can only be sold by investment professionals with suitable training and credentials.

But regardless of the kind of professional you go to for investment advice, the underlying ethical question is whether that professional is going to have your best interests at heart. When the thing you’re buying is too complex to understand, you have to put your trust in the seller. Such trust is best underpinned by what are called fiduciary duties. A fiduciary, roughly speaking, is someone to whom something of value is entrusted. And a professional who bears a fiduciary duty has a stronger obligation than a mere salesman. Someone out to sell you something — a car, a stereo, whatever — has a plain obligation not to deceive you, but generally isn’t obligated to make sure that the product is right for you. Whether the product is right for you is up to you to decide. But a fiduciary is held to a higher standard. As Alexei Marcoux points out, we are vulnerable in various ways to professionals of various kinds, and that vulnerability generates duties on the part of those professionals, not just to be honest to us but to put our interests first. The transaction between a professional and a client is not a regular market transaction; rather, it is (or ought to be) governed by the higher standard implied by a fiduciary relationship.

Whether financial advisors and financial planners proclaim and live up to such a high standard is another matter. It certainly seems they should. In some places, financial professionals are explicitly expected to live up to the standard applied by a fiduciary duty, and other jurisdictions are moving in that direction. If ever there were a circumstance in which we were vulnerable, a situation in which we are trusting a stranger to tell us what to do with our life’s savings seems to fit the bill.

Did GE Really Pay No Taxes in 2010?

A few months back, the NY Times shocked a lot of people by reporting that General Electric — an enormous, multi-billion-dollar company — had paid zero taxes to the US government in 2010, despite the fact that more than a third of the $14.1 billion that company earned that year had come from its US operations. The reason? GE has a truly enormous tax department that works non-stop to look for deductions and loopholes.

Scandalous, right?

Not so quick. As I’ve argued before, what we commonly call “loopholes” are in most cases the result of some decision by government to encourage or discourage a particular behaviour. That is, most of the things GE (or any other company) does in order to avoid taxes are thing the government is trying, however ham-fistedly, to encourage companies to do. Still, we might reasonably look askance at a company that works so assiduously to squeeze every last dollar out of the tax system. The millions spent to save millions in taxes could in principle be spent to develop products that would boost the overal value proposition of the company.

But the situation with regard to GE is even more complex than that. To get a taste, check out the comments section under the discussion of this story on the always-useful economics blog, Marginal Revolution. There, it is pointed out that the $14.1 billion in profits attributed to GE by the NYT was calculated according to GAAP, which is entirely different from how the IRS calculates taxable income. In other words, we’re looking at apples and oranges here. The entire discussion thread at MR is worth reading. But if you’re not well-versed in the niceties of tax rules, or corporate finance more generally, you’ll quickly find yourself in over your head.

But that in itself raises an important issue. As the sophistication of the debate in the MR comments section demonstrates, the fairness of GE’s tax burden (or lack thereof!) is something that most of us simply are not qualified to comment upon. And that’s a worry. It’s hard for companies to be held accountable if the general public doesn’t understand the factual basis for evaluating them. It seems to me that this is an additional reason for tax reform: the subtlety of the various policy objectives being sought through taxation of corporations needs to be balanced against the need for the concerned public to be able understand it.

Wall Street Needs to be Fixed, Not Occupied

Issues of corporate ethics are too important to leave to the Occupy Wall Street gang. The principles the group is fighting for are noble ones, but the tools they employ leave much to be desired. It’s up to the rest of us to use better tools.

Those currently camped out in New York, and other cities across the US, are right to want better corporate ethics, including a big dose of accountability and transparency. And they’re right to want to live in a just and equitable society. And they’re right to want certain kinds of electoral reform: finding ways to limit the influence of corporations (without stomping on free speech) would be a very good thing. But occupying Wall St. isn’t going to do it.

Don’t get me wrong: I’m there, in spirit. Well, not there there. I’m not likely to join the sit-in anytime soon; those methods aren’t my methods. But I sympathize with the frustration manifested by the passionate, non-partisan cabal of well-intentioned folks who make up the Occupy Wall Street movement. Indeed, though our methods are radically different, I’ve dedicated my career to some of the same ideals. I’m committed to the project of figuring out the best possible standards for corporate structures and behaviours, and I hope that better understanding will lead, indirectly, to better outcomes. The folks of the “Occupy Wall Street” movement likely think my way won’t won’t have much impact. Don’t worry, I’m not taking it personally.

The Occupy Wall Street movement has substantial symbolic significance, but we all know, I think, that nothing concrete is going to come of it. To start with, the mechanism is all wrong — it’s not like corporate and political elites are going to see a sit-in, and suddenly going to smack their foreheads and say, “Oh, ok! Let’s make changes!” And then there’s the movement itself. It’s pretty clear by now that the loosely-organized movement doesn’t have much in the way of concrete goals. And its spokespeople can barely open their mouths on topics related to business and economics without saying things that are grossly mistaken. Their values are right, but the mechanisms they envision to implement those values — things like repealing corporate personhood — are deeply misguided. But then, to look for direct impact is, as others have observed, likely a mistake, and misses the real significance of the movement.

So it would be easy — too easy ‐ to dismiss Occupy Wall Street as a bunch of well-intentioned young people tilting at windmills. But that would be a mistake. The windmills they’re tilting at are important ones.

The real value of the Occupy Wall Street movement is that it ought to serve as a kick in the pants to the rest of us, an inspiration to make use of tools that will do some real good. Let’s leverage their energy into effective methods. So think. Learn about the issues. Learn about corporate governance. Advocate reform. Organize. Get out the vote. If Occupying Wall Street is to have any real impact, it won’t be by motivating a few hundred more people to camp out in the street.

Chasing Madoff (movie review)

The documentary Chasing Madoff opens this week. I had a chance to attend a preview of the movie last night (courtesy of eOne Films).

The documentary Chasing Madoff opens this week. I had a chance to attend a preview of the movie last night (courtesy of eOne Films).

The film is really the story of fraud investigator Harry Markopolos, the guy who, while working as an options trader at Rampart Investment Management, discovered Madoff’s scheme and worked valiantly to get the Securities and Exchange Commission to take notice.

It’s kind of a fun film, but not a great film. The film lacks a narrator, opting instead to tell the entire story through the first-hand accounts of a handful of people (primarily Markopolos and a couple of colleagues, along with a few of Madoff’s victims) and snippets from newscasts. The focus on first-person accounts gives the film a personal feel, but it also inevitably means a perspective that is slanted, though perhaps not fatally so.

There are a few laughs in the film. Markopolos is a bit of a strange cat. He’s a likeable guy, and apparently a man of integrity, but also a bit paranoid-sounding. On-screen, he tells us that he feared Madoff so much that he was ready to pre-emptively shoot the guy, if Madoff had discovered his investigation. He also describes what his strategy would be in the event of an armed standoff with the SEC, should they ever come to his home to get his files — files that included damning evidence of SEC complacency. Just for emphasis, one scene shows him leaning against his desk, brandishing a pump-action shotgun. These humourous parts are, I think, intentional, or at least surely the director (Jeff Prosserman) must have known they would spark laughter. And humour is fine, but it tends to undercut the filmmakers’ stated intention of generating outrage in their audience.

What’s most striking, perhaps, about Chasing Madoff is what it doesn’t tell us about the Madoff scandal. For example, it points fingers at the SEC, but tells us nothing about the agency’s funding levels, and whether it had the capacity to keep up with complaints like Markopolos’s as they flowed in. There are also allegations that “someone higher up” at the Wall Street Journal tried to stifle the story before it broke, but little evidence to back that up. And there are intriguing hints about the large number of individuals and organizations that must have been complicit in Madoff’s crimes, and hints at why they had no economic incentive not to keep putting faith in his results. There’s even a claim that Madoff “paid top dollar” to those that would bring him “new victims.” But the relevant parties are not named and the film makes little effort to explain the connections.

Bottom line: I’m a university professor — would I show this movie in my Business Ethics classroom? Probably not. It’s a fine portrayal of man of integrity fighting the good fight, but it teaches relatively little about how the financial crime of the century happened, or what if anything would prevent it from happening again.

Executives and their Income

I’ve blogged a number of times about what is commonly and loosely called “executive compensation.” The term is woefully imprecise. In point of fact, most “compensation” is not, in fact, compensation. The carrot dangled in front of a horse is not compensation; it is motivation. Compensation is what you give someone after the fact as reward for a job well done, or at least for a job that met contractual requirements. If I hire the neighbour’s kid to mow the lawn, and he does so, then I should compensate him. Most of the money garnered by senior executives at publicly-traded companies these days is not, in fact compensation. It’s money they get from selling shares in the company, shares granted to them as part of an effort to align their interests with the interests of shareholders.

The looseness of use of that word in the realm of finance is not at all unique. Witness the “bonuses” paid to AIG employees two years ago, which were not in fact performance bonuses at all but rather retention payments designed to keep key employees on what seemed at the time to be a sinking ship.

See more recently this piece by Peter Whoriskey for the Washington Post: With executive pay, rich pull away from rest of America. Here’s just a taste:

The top 0.1 percent of earners make about $1.7 million or more, including capital gains. Of those, 41 percent were executives, managers and supervisors at non-financial companies, according to the analysis, with nearly half of them deriving most of their income from their ownership in privately-held firms….

Notice that (contrary to the article’s title) the key factor in the growth of executive income here is not in fact “pay.” The key factor is investment income. And it’s not even “pay” in the loose sense of ‘money given by an employer,’ since there’s no indication here what portion of that investment income comes from shares in a CEO’s own company, say, versus a diversified portfolio. But it’s hard to hold Whoriskey to blame for the linguistic imprecision here; confusing pay and compensation and income is altogether standard.

The other point to be made here is about justice. According to Whoriskey, “…executive compensation at the nation’s largest firms has roughly quadrupled in real terms since the 1970s, even as pay for 90 percent of America has stalled…” Setting aside imprecision of language, that suggests a significant disparity — not disparity of outcomes (which are a given, here) but disparity of rate of improvement.

Now according to Leslie McCall, a sociologist quoted in Whoriskey’s story, people become concerned about such inequality “…when it seems that extreme incomes for some are restricting opportunities for everyone else.” And that may be true about people’s reactions. But of course, it’s very hard for people to tell when it is actually the case that extreme incomes for some are restricting opportunities for others. As economists often point out, income is not a fixed pile, waiting to be handed out. The way you distribute income actually changes the size of the ‘pie’ due to the way money incentivizes. Incentivizing executives with stock and stock options may on the whole be a failed experiment, but that doesn’t change the fact that it is impossible to know whether the average worker would be better or worse off had those incentives never been offered.

Rajaratnam: Insider Trading, Soft Skills, and Slippery Slopes

Yesterday, Raj Rajaratnam, founder and head of hedge-fund management firm, The Galleon Group, was found guilty of 14 separate counts of securities fraud and conspiracy.

I think two things are worth talking about, with regard to this case.

1) One is the extent to which Rajaratnam was apparently a master of the so-called ‘soft skills’ of business. Rajaratnam’s success (and his eventual downfall) was rooted to a large extent in his talent for extracting insider information from his network of corporate contacts, charming them into revealing their employers’ secrets. To get a sense of this, it’s worth reading this richly detailed piece by Peter Lattman and Azad Ahmed, for the New York Times: Galleon Chief’s Web of Friends Proved Crucial to Scheme. Here’s a taste:

In his soft-spoken manner, shaped by his years at secondary school and college in England, Mr. Rajaratnam alternately prodded, chided, ridiculed and flattered his sources. Above all, he was a good listener, saying little as those on the other end of the phone, eager to impress the hedge fund titan, kept talking….

In other words, this ‘hedge fund titan’ used the same interpersonal skills in pursuit of millions as the common scam artist uses in pursuit of the little old lady’s retirement savings. This fact reinforces the importance of teaching these skills — and teaching about the dangers inherent in misusing them — in business schools.

2) The second point worth discussing has to do with grey zones and slippery slopes. Rajaratnam was found guilty of a criminal variant of something that professional investors do all the time, namely gathering information from people who know stuff about the firms those investors are considering investing in. In order to make their case, prosecutors would have had to convince the jury that Rajaratnam’s intelligence-gathering wasn’t just the run-of-the-mill kind.

But it’s also worth pointing out that there’s more than just a binary distinction to be made here. Somewhere between benign information-gathering, on one hand, and criminal insider trading, on the other, is a category of ethically-suspect behaviour that involves asking corporate insiders to provide ‘perspective’ or an ‘overview’ of, for example, the financial health of their firms. Such behaviour can be unethical for the same reason actual insider trading is illegal. Corporate insiders have fiduciary duties — duties rooted in trust — and providing information to outsiders so that they can have a trading advantage is a betrayal of that trust. And Rajaratnam’s methods played on his accomplices’ uncertainty about where to draw the relevant lines. The slope from benign to unethical to illegal is, it seems, quite slippery, especially when that slope is greased with flattery and a few hundred thousand dollars.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment