Archive for the ‘CSR’ Category

Pink Toenails, Gender Identity and Social Responsibility

This one’s a real tempest in a teapot. Or rather, in a bottle of nail polish.

This one’s a real tempest in a teapot. Or rather, in a bottle of nail polish.

OK, so here’s the short version. Clothing chain J. Crew’s latest catalog includes a picture of president and creative director Jenna Lyons painting her young son’s toenails pink. Yes, pink — the colour most closely associated, in North American culture, at least, with traditional femininity. Criticism ensued, alleging that J. Crew was acting (intentionally!) to promote a gender-bending agenda. The calibre and cogency of the arguments in favour of that conclusion is about what you’d expect.

The main critic, Fox commentator and psychiatrist Dr Keith Ablow, provides an object lesson in how to cram as many argumentative fallacies as possible into a single piece of writing, in his oddly-titled editorial, “J. Crew Plants the Seeds for Gender Identity”. (I’ve blogged about the significance of logical fallacies before, here.) Among the good doctor’s fallacious arguments:

He alleges, without substantiation, that pink-toenail-painting is highly likely to result in gender confusion. In the absence of supporting evidence, we are expected to believe him because he’s got “Dr” in front of his name — essentially a form of illicit appeal to authority. He also engages in straw man argumentation (in which a critic attacks something his opponent never said nor implied), by suggesting that, via this ad, “our culture is being encouraged to abandon all trappings of gender identity” [my emphasis]. He also begs the question by assuming that pink is just for girls (and I’m wearing pink as I write this, by the way). He also has an unfortunate tendency to resort to rhetorical questions: “If you have no problem with the J. Crew ad, how about one in which a little boy models a sundress? What could possibly be the problem with that?” (What if my answer is “nothing”? Ablow provides nothing to help me, then.) Ablow also commits the fallacy known as appeal to ignorance when he points out that the effect of “homogenizing males and females … is not known” (i.e., we don’t know that it’s safe, so it is probably unsafe.) He also makes use of an illicit slippery slope argument, suggesting comically that ads such as this are somehow going to result in the end of all procreation, and, hence, of the human race. And Ablow’s argument as a whole amounts to one giant, fallacious, appeal to tradition. I could quite literally teach the entire Fallacies section of my Critical Thinking class just by having students pick apart Ablow’s critique of the J. Crew ad.

(Note that another critic, Erin Brown, over at the conservative Culture and Media Institute, commits fewer fallacies, but only because her article is shorter. But then she apparently doen’t even know what J. Crew is, referring to the men’s and women’s clothier as a “popular preppy woman’s clothing brand.” I happen to own two J. Crew ties. Men’s ties.)

Now, my response to the critics of J. Crew’s ad may seem flippant. So be it. Sometimes ridicule is the best response to something ridiculous. But there is a serious point to be made, here, about the social responsibility of business.

Ablow and Brown share one important view in common with many critics of modern capitalism, namely this: they all believe that businesses have an obligation to pursue certain social agendas. They merely disagree over what that agenda should be. For Ablow and Brown, the social obligation of business is to defend & promote good ol’-fashioned American values, including apparently carefully scripted gender roles. For critics of capitalism, the social obligation of business is to promote social justice, environmental values, gender equality, and so on. In either case, those who urge businesses to adopt social missions — as opposed to merely making and selling stuff that people want to buy, within the bounds of law and ethics — ought to be careful what they wish for. Because if and when businesses do take up social agendas, they may not be the agendas that those advocates prefer.

—-

Thanks to Laura for showing me this story.

Business Ethics and the Crisis in Japan

A couple of people have asked me recently about what business ethics issues arise in the wake of the Japanese earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear crisis. As far as I’ve seen, the media hasn’t paid much attention to business ethics issues, or even on businesses at all, in their coverage of the disaster(s). But certainly there are a number of relevant issues within which appropriate business behaviour is going to be a significant question. Here are a few suggestion of areas in which the study of business ethics might be relevant:

A couple of people have asked me recently about what business ethics issues arise in the wake of the Japanese earthquake, tsunami, and nuclear crisis. As far as I’ve seen, the media hasn’t paid much attention to business ethics issues, or even on businesses at all, in their coverage of the disaster(s). But certainly there are a number of relevant issues within which appropriate business behaviour is going to be a significant question. Here are a few suggestion of areas in which the study of business ethics might be relevant:

1) The nuclear crisis. Although their role has not been front-and-centre (unlike, for example, the BP oil spill), at least a couple of companies have played a significant role in the crisis at the Fukushima I Nuclear Power Plant. The reactors there were designed by General Electric, who surely face questions about the adequacy of that design and the relevant safeguards. And the plant is owned by the Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO). TEPCO has been criticized for its handling of the disaster, including its notable lack of transparency. TEPCO also faces a difficult set of questions with regard to the ongoing risks to employees, including those who have vowed “to die if necessary” in order to protect the public from further risk. (For more information, see the wikipedia page about the Fukushima I nuclear accidents.)

2) Disaster relief. There is clearly an opportunity for many companies, both Japanese and foreign, to participate in the disaster relief effort. Whether they have an obligation to do so (i.e., a true corporate social responsibility) is an interesting question, as is the question of the terms on which they should participate. I’ve blogged before about the essential role that credit card companies play in disaster relief by facilitating donations; do credit card companies (and other companies) have an obligation to help out on a not-for-profit basis, or is it OK to make a profit in such situations?

3) Pricing. The topic of price-gouging often arises during and after a natural disaster, though I haven’t heard any reports of this in the wake of the earthquake in Japan. It’s a difficult ethical question. On one hand, companies that engage in true price gouging — preying on the vulnerable in a truly cynical and opportunistic way — are rightly singled out for moral criticism. On the other hand, prices naturally go up in the wake of disaster: picture the additional costs and risks that any company is going to face in trying to get their product into an area affected by an earthquake, a tsunami, and/or a nuclear meltdown.

4) Investment and trade. A major part of Japan’s recovery will depend on investment, both investment by foreign companies in Japan and investment by Japanese companies in the stricken areas of that country. This is clearly less of a concern than it would be in a less-economically developed country (like Haiti, for instance), but it’s still relevant. So the question arises: do companies have an obligation to help Japan rebuild by investing? If a company is, for example, deciding whether to build a new factory in either Japan or another country, should that decision be influenced by the desire to help Japan rebuild?

5) Consumer behaviour. Just as companies have to decide whether to invest in disaster-stricken nations or regions, so do consumers. Do you, as an individual, have any obligation to “buy Japanese,” in order to help rebuild the Japanese economy? Does it matter that Japan is a modern industrialized nation, as opposed to a developing one?

Financial Speculation & Ethics

Friday I gave a talk as part of a terrific workshop on the ethics and law of financial speculation, held at the University of Montreal. (The event was co-sponsored by U of M’s Centre for Business Law and the Centre for Research in Ethics.)

As I mentioned in a posting last week, financial speculation is the subject of some controversy. Indeed, there has been plenty of discussion of regulating various forms of speculation, though whether that is possible and how best to do so is also subject to controversy.

Very roughly, “speculation” can be thought of as involving any of a range of forms of relatively high-risk investment. In a way, it is the exact opposite of a slow, safe investment such as buying government savings bonds. But it’s also different from pure gambling: in most forms of gambling, you have no reasonable expectation of making money. You might well win big, and it’s nice if you do, but really all you can expect is to have fun playing the game. Speculation on the other hand involves taking what are hopefully well-informed risks, in the hopes of exceptional returns.

Here are 3 stereotypical examples of speculation:

- Imagine that a wheat farmer is considering whether to plant wheat an additional, previously-unplanted, field. Imagine that the farmer’s total cost for doing so would be $5/bushel of wheat. If the current price of wheat is hovering right around the $5 mark, that turns planting into a risky proposition. The risk of a loss might make planting just too unattractive. Now imagine a speculator comes along and is willing to take that risk, so she offers the farmer $5.25/bushel for the wheat that has not even been planted yet. With the promise of a modest-but-guaranteed profit in hand, the farmer plants the crop. If, at harvest time, the price of wheat has gone up to $6/bushel, the speculator stands to make a tidy profit. If the price has gone down to $4/bushel, the speculator suffers a loss — but she’s in the business of speculating precisely because she has the resources to absorb such losses, and will just hope that her next investment pays off better.

- Imagine someone whose job is to invest in futures contracts on commodities such as oil or gold. A futures contract is basically a commitment to buy a specified quantity of something, at a specified price, at some date in the future. The example above involved a kind of futures contract, except in that example the investor actually did intend to buy and take possession of the farmer’s wheat once harvested. But in the vast majority of futures trading, nothing but paper ever changes hands. If a trader finds that other traders have been paying above-market prices for oil futures, she might decide that it’s worth buying some herself, in the hope that the price of oil will continue to go up because of this demand. Other traders are likely to notice, and imitate, her behaviour, with a net effect of pushing oil prices up. None of this needs to reflect any underlying change in consumer demand for oil, or any change in oil’s supply. It can all happen as the result of a combination of hunches about the future of oil and a dose of herd behaviour.

- Imagine I have a dim view of the future prospects of a company, say BP, so I decide to “short” (sell short) shares in BP. What I do is I borrow some shares in BP, say an amount that would be worth $1,000 at today’s prices. I then sell those borrowed shares. If all goes as I expect it will, the price of BP shares may drop — let’s imagine it drops 25%. I can then buy enough shares in BP, at the reduced price ($750 total), to “return” the shares to the person I originally borrowed them from. And I get to pocket the $250 difference (minus any expenses). Basically, this form of speculation — short selling — is unlike standard investments in that it involves betting that a company’s shares will go down, rather than up, in value.

There is disagreement among experts regarding just what the net effect of speculation (or indeed of particular kinds of speculation) is likely to be. Some think that speculation, as a kind of artificial demand, has the tendency to increase prices and perhaps even to result in “bubbles” that eventually burst, with tragic results. But the evidence is unclear. In particular cases, it can be very difficult to tell whether a) speculation caused the inflationary bubble, or whether b) some underlying inflationary trend spurred speculation, or whether c) it was a bit of both. And even if it’s clear that some forms of speculation sometimes have such effects, it’s not clear a) that speculation has negative effects often enough to warrant intrusive regulations, or b) that regulators will be able to single out and regulate the most worrisome forms of speculation without stomping out the useful forms.

And defenders of speculation do point out that at least some forms of speculation have beneficial effects. Speculators of the sort described in my first example above take on risk that others are unable to bear, and hence allow productive activity to take place that otherwise might not. They also add “liquidity” to markets by increasing the number of willing buyers and sellers. Speculators, through their investments, can also bring information into the market and thus render it more efficient. When one or more speculators takes a special interest in a given commodity, it is likely to be on account of some special insight or analysis that suggests that there will be an increased need for that commodity in the future. In other words, in the best cases at least, expert financial speculation isn’t idle speculation — it is well-informed, and informative.

Of course, it’s also worth pointing out that pretty much any technology or technique can be used for good or for evil. The techniques of financial speculation can be used to attempt to manipulate markets or to defraud consumers. Whether the dangers of such uses outweigh other considerations is up for debate.

But from the point of view of ethics, it’s worth at least considering exercising caution in some areas. Perhaps speculators with a conscience, for example, should be particularly risk-averse when it comes to commodities that have a very direct impact on people’s wellbeing, such as food. Recently Andrew Oxlade, writing for the financial website “ThisIsMoney”, asked Is it ethical to invest in food prices? As Oxlade notes, at least some critics believe that recent surges in food commodity prices have at least something to do with the activities of traders engaging in speculative trades.

Oxlade offers this advice to investors:

To sleep easier at night and still get exposure to this area, you may want to consider investing in farming rather than in food prices via derivatives. In fact, your money may even do some good.

———————-

p.s. thanks once again to the organizers of the workshop mentioned above, namely professors Peter Dietsch and Stéphane Rousseau.

————

Note also: If you’re interested in this topic from a professional or academic point of view, then this book should be on your bookshelf: Finance Ethics: Critical Issues in Theory and Practice, edited by John Boatright.

Socially Responsible Investing & Value Alignment

Socially responsible investing (SRI) is a big topic, and a complex issue, one about which I cannot claim to know a lot. The basic concept is clear enough: when people make investments, they send their money out into the world to work for them. People engaged in SRI are trying to make sure that their money is, in addition to earning them a profit, doing some good in the world, rather than evil.

There are a number of kinds of SRI. For example, there are investment funds that use “negative screens” (to filter out harmful industries like tobacco), and there are “positive investment” (in which funds focus on investing in companies that are seen as producing positive social impact). We can also distinguish socially-responsible mutual funds from government-controlled funds, such as pension funds.

(For other examples, check out the Wikipedia page on the topic, here.)

Setting aside the kinds of distinctions mentioned above, I think we can usefully divide socially responsible investments into two categories, from an ethical point of view, rooted in 2 different kinds of objectives.

On one hand, there’s the kind of investment that seeks to avoid participating in what are relatively clear-cut, ethically bad practices. For example, child slavery. Trafficking in blood diamonds might be another good example. Responsible investment in this sense means not allowing your money to be used for what are clearly bad purposes. In this sense, we all ought to engage in socially-responsible investment.

(Notice that investments avoiding all child labour do not fall into the above category, because child labour, while always unfortunate, is not always evil. There are cases in which child labour is a sad necessity for poor families.)

On the other hand, there’s what we might call “ethical alignment” investments, in which a particular investor (small or large) attempts to make sure their money is invested only in companies or categories of companies that are consistent with their own values. Imagine, for example, a hard-core pacifist refusing to invest in companies that produce weapons even for peace-keeping purposes. Or picture a labour union investing only in companies with an excellent track-record in terms of labour relations. In such cases, the point is not that the corporate behaviour in question is categorically good or bad; the point is that they align (or fail to align) with the investor’s own core values.

I’m sure someone reading this will know much more about SRI than I do. Is the above distinction one already found in that world?

Pepsi Makes the Best of a Super Bowl-Free Sunday

Talk about making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. PepsiCo has managed to make a win out of not sponsoring the biggest advertising event of the year.

Talk about making a silk purse out of a sow’s ear. PepsiCo has managed to make a win out of not sponsoring the biggest advertising event of the year.

See the story here, by Jennifer Preston of the NYT: Pepsi Bets on Local Grants, Not the Super Bowl

What’s better than reaching more than 100 million viewers during last year’s Super Bowl? For Pepsi, it could be 6,000 football fans during a high school game on Friday night in central Texas. Or a group of parents who wanted a new playground in their Las Vegas neighborhood.

That is the bet that PepsiCo made when it walked away from spending $20 million on television spots for Pepsi during last year’s Super Bowl and plowed the money into a monthly online contest for people to submit their ideas and compete for votes to win grants….

This is the first time in 23 years that Pepsi isn’t a sponsor of the Super Bowl. How did this happen? Who knows. Maybe the price-tag got too rich for them. Maybe they got outbid. (Though it’s worth noting that PepsiCo won’t be entirely absent from the Super Bowl: the game will feature ads for two of the company’s other brands, Pepsi Max and Doritos.) At any rate, Pepsi says it’s just a new strategy. Interestingly, they say — despite the fact that this new strategy involves giving millions of dollars to good causes — it’s not a philanthropic strategy:

“This was not a corporate philanthropy effort,” said Shiv Singh, head of digital for PepsiCo Beverages America. “This was using brand dollars with the belief that when you use these brand dollars to have consumers share ideas to change the world, the consumers will win, the brand will win, and the community will win.

It’s an interesting move. For one thing, it brings together cause-based marketing and social media on a supersized scale. And to me, whatever the motivation for the move, it’s a true-and-justified instance of corporate social responsibility. It’s not ethically obligatory: I don’t think there’s anything wrong with doing things the old way. It’s not unethical to spend $20 million-plus on commercials for the Super Bowl, like they did last year. And it’s not obligatory to support dozens or hundreds of local causes. So think of it this way: PepsiCo has $20 million to spend on building its brand. It had to choose a strategy, a choice regarding how to spend that money. They could give it to the NFL, or they could give it to a bunch of worthy charities. If they can achieve their objectives (and hence fulfill obligations to shareholders) while at the same time doing some social good, that’s a good example of CSR.

As the company says, though, it’s a gamble. But as gambles go, they’re sure making the best of it. PepsiCo is turning not sponsoring the Super Bowl into a straight-up victory, rather than a defeat. And notice also that, with the right media coverage, Pepsi still gets its name associated with the Super Bowl.

MTV’s “Skins”: The Ethics of Profiting from Teen Sexuality

There’s been a lot of chatter in the last few days about MTV’s teensploitation show, “Skins.” Of course, one theory says that that’s just what MTV has been hoping for — a lot of free advertizing.

I’m quoted giving a business-ethics perspective on the show in this story, by the NYT’s David Carr: “A Naked Calculation Gone Bad.”

What if one day you went to work and there was a meeting to discuss whether the project you were working on crossed the line into child pornography? You’d probably think you had ended up in the wrong room.

And you’d be right.

Last week, my colleague Brian Stelter reported that on Tuesday, the day after the pilot episode of “Skins” was shown on MTV, executives at the cable channel were frantically meeting to discuss whether the salacious teenage drama starring actors as young as 15 might violate federal child pornography statutes.

Since I’m quoted in that story, I’ll just cut to my own conclusion:

“Even if you decide that this show is not out-and-out evil and that the show is legal from a technical perspective, that doesn’t really eliminate the significant social and ethical issues it raises,” said Chris MacDonald, a visiting scholar at the University of Toronto’s Clarkson Center for Business Ethics and author of the Business Ethics Blog. “Teenagers are both sexual beings and highly impressionable, and because of that, they’re vulnerable to just these kinds of messages. You have to wonder if there isn’t a better way to make a living.”

I wouldn’t bet one way or the other on how this will turn out — in particular on whether pressure from advocacy groups and advertisers will convince MTV to can the show. If it does, then this controversy turns into a nice example of how just the wrong kind of corporate culture can produce bad results. Consider: there are an awful lot of people involved in conceiving and producing, and airing a TV drama. In order for Skins to make it to air, a lot of people had to spend months and months going with the flow, basically saying to themselves and each other “Yes, it is a really good idea to show teens this way, to use teen actors this way, and to market this kind of show to teens.” Hundreds of people involved in the production must have either thought it was a good idea, or thought otherwise but decided they couldn’t speak up. If this turns out badly, MTV will have provided yet another example of how things can go badly when employees aren’t encouraged and empowered to speak up and to voice dissent.

Sustainability is Unsustainable

I was tempted to call this blog entry “Sustainability is Stupid,” but I changed my mind because that’s needlessly inflammatory. And really, the problem isn’t that the concept itself is stupid, though certainly I’ve seen some stupid uses of the term. But the real problem is that it’s too broad for some purposes, too narrow for others, and just can’t bear the weight that many people want to put on it. The current focus on sustainability as summing up everything we want to know about doing the right thing in business is, for lack of a better word, unsustainable.

Anyway, I am tired of sustainability. And not just because, as Ad Age recently declared, it’s one of the most jargon-y words of the year. Which it is. But the problems go beyond that.

Here are just a few of the problems with sustainability:

1) Contrary to what you may have been led to believe, not everything unsustainable is bad. Oil is unsustainable, technically speaking. It will eventually get scarce, and eventually run out, for all intents and purposes. But it’s also a pretty nifty product. It works. It’s cheap. And it’s not going away soon. So producing it isn’t evil, and using it isn’t evil, even if (yes, yes) it would be better if we used less. Don’t get me wrong: I’m no fan of oil. It would be great if cars could run on something more plentiful and less polluting, like sunshine or water or wind. But in the meantime, oil is an absolutely essential commodity. Unsustainable, but quite useful.

2) There are ways for things to be bad other than being unsustainable. Cigarettes are a stupid, bad product. They’re addictive. They kill people. But are they sustainable? You bet. The tobacco industry has been going strong for a few hundred years now. If that’s not sustainability, I don’t know what is. To say that the tobacco industry isn’t sustainable is like saying the dinosaur way of life wasn’t sustainable because dinosaurs only ruled the earth for, like, a mere 150 million years. So, it’s a highly sustainable industry, but a bad one.

3) There’s no such thing as “sustainable” fish or “sustainable” forests or “sustainable” widgets, if by “sustainable” you mean as opposed to the other, “totally unsustainable” kind of fish or forests or widgets. It’s not a binary concept, but it gets sold as one. A fishery (or a forest or whatever) is either more or less sustainable. So to label something “sustainable” is almost always greenwash. Feels nice, but meaningless.

4) We’re still wayyyy unclear on what the word “sustainable” means. And I’m not talking about fine academic distinctions, here. I’m talking big picture. As in, what is the topic of discussion? For some people, for example, “sustainability” is clearly an environmental concept. As in, can we sustain producing X at the current rate without running out of X or out of the raw materials we need to make X? Or can we continue producing Y like this, given the obvious and unacceptable environmental damage it does? For others, though — well, for others, “sustainability” is about something much broader: something economic, environmental, and social. This fundamental distinction reduces dramatically the chances of having a meaningful conversation about this topic.

5) Many broad uses of the term “sustainable” are based on highly questionable empirical hypotheses. For example, some people seem to think that “sustainable” isn’t just an environmental notion because, after all, how can your business be sustainable if you don’t treat your workers well? And how can you sustain your place in the market if you don’t produce a high-quality product? Etc., etc. But of course, there are lots of examples of companies treating employees and customers and communities badly, and doing so quite successfully, over time-scales that make any claim that such practices are “unsustainable” manifestly silly. (See #2 above re the tobacco industry for an example.)

6) We have very, very little idea what is actually sustainable, environmentally or otherwise. Sure, there are clear cases. But for plenty of cases, the correct response to a claim of sustainability is simply “How do you know?” We know a fair bit, I think, about what kinds of practices tend to be more, rather than less, environmentally sustainable. But given the complexities of ecosystems, and the complexities of production processes and business supply chains, tracing all the implications of a particular product or process in order to declare it “sustainable” is very, very challenging. I conjecture that there are far, far more claims of “sustainability” than there are instances where the speaker knows what he or she is talking about.

7) Sometimes, it’s right to do the unsustainable thing. For example, would you kill the last breeding pair of an endangered species (say, bluefin tuna, before long) to feed a starving village, if that was your only way of doing so? I would. Sure, there’s room for disagreement, but I think I could provide a pretty good argument that in such a case, the exigencies of the immediate situation would be more weighty, morally, than the long-term consequences. Now, hopefully such terrible choices are few. But the point is simply to illustrate that sustainability is not some sort of over-arching value, some kind of trump card that always wins the hand.

8 ) The biggest, baddest problem with sustainability is that, like “CSR” and “accountability” and other hip bits of jargon, it’s a little wee box that people are trying to stuff full of every feel-good idea they ever hoped to apply to the world of business. So let’s get this straight: there are lots and lots of ways in which business can act rightly, or wrongly. And not all of them can be expressed in terms of the single notion of “sustainability.”

Now, look. Of course I don’t have anything against sustainability per se. I like the idea of running fisheries in a way that is more, rather than less, sustainable. I like the idea of sustainable agriculture (i.e., agriculture that does less, rather than more, long-term damage to the environment and uses up fewer, rather than more, natural resources). But let’s not pretend that sustainability is the only thing that matters, or that it’s the only word we need in our vocabulary when we want to talk about doing the right thing in business.

Glock Pistols, Ethics and CSR

It’s been a week now since the Tuscon, Arizona killings in which Jared Lee Loughner apparently emptied the high-capacity magazine of his 9 mm pistol.

It’s been a week now since the Tuscon, Arizona killings in which Jared Lee Loughner apparently emptied the high-capacity magazine of his 9 mm pistol.

Plenty has already been written about the awful killing. Inevitably, some of it has focused on the weapon he carried, namely the Glock. According to Wikipedia’s Glock page,

The Glock is a series of semi-automatic pistols designed and produced by Glock Ges.m.b.H., located in Deutsch-Wagram, Austria.

…

Despite initial resistance from the market to accept a “plastic gun” due to concerns about their durability and reliability, Glock pistols have become the company’s most profitable line of products, commanding 65% of the market share of handguns for United States law enforcement agencies[5] as well as supplying numerous national armed forces and security agencies worldwide….

If you want to learn more about the company that made the pistol Loughner used, see this article, by Paul M. Barrett for Bloomberg Businessweek, Glock: America’s Gun

…Headquartered in Deutsch-Wagram, Austria, the company says it now commands 65 percent of the American law enforcement market, including the FBI and Drug Enforcement Administration. It also controls a healthy share of the overall $1 billion U.S. handgun market, according to analysis of production and excise tax data. (Precise figures aren’t available because Glock and several large rivals, including Beretta and Sig Sauer, are privately held.) ….

Barrett’s article provides a fascinating account of the invention of the Glock pistol and how it came to its current dominant market position through a combination of excellent engineering, good marketing and cagey lobbying.

The sale of semi-automatic pistols with high-capacity magazines is a good example of an issue where the term “corporate social responsibility” provides a useful analytic lens. I’ve argued here before that the term “CSR” is over-used — we shouldn’t try to stuff every single ethical issue into the relatively narrow notion of corporate social responsibility. But like the BP oil spill, the current case raises issues that are genuinely social in nature. As difficult as it may be, set aside for a moment the tragic events of January 8th, and look at the marketing of the Glock pistol (and its accessories) from a social point of view.

Do Americans as individuals have the right to buy certain kinds of weapons? As a matter of constitutional law, yes. And there’s arguably no direct line to be drawn between the sale of an individual gun and a particular wrongful death (because there’s always the complicating factor of the decision made by the individual who bought the gun and then pulled the trigger). So let us take as given (even if just for the sake of argument) that there’s nothing intrinsically wrong with making and selling guns to the public. Let us assume that individual customers have a legitimate interest in owning semi-automatic pistols, and there’s nothing unethical about a company seeking to make money from satisfying the demand for this entirely-legal product.

That still leaves as an open question, I think, the question of social impact. The best rationale for public acceptance of the kind of zealous, profit-seeking behaviour seen in the world of business lies in the social benefits that arise from a vigorous competitive marketplace. This implies that the moral limits on business are also to be found in a business’s net social impact.

There is a raging debate, in the US, over the net social impact of the sale of handguns. And where a product is contentious, you can argue that “the tie goes to the runner,” and that the “runner” in this case is freedom. When in doubt, opt for freedom of sale and choice. So let’s say (again, if only for sake of argument) that there’s nothing wrong with selling handguns to the public. So Glock (the company) is justified in existing and in carrying out its business. That still leaves open the question of the particular ways in which handguns and their accessories are marketed. The social benefits of selling handguns may be fundamentally contentious; in other words, reasonable people can agree to disagree. But I doubt that the same can really be said for marketing moves designed, for example, to foster the sale of high-capacity magazines (ones that hold 33 bullets instead of the usual 17).

I’m not presuming to answer that question here; I’m merely pointing out the significance, and appropriateness, of a specifically social lens.

——

(See also Andrew Potter’s characteristically sane piece on the politics of gun control: ‘You can’t outsmart crazy’—or can you?)

Greenpeace, Tar Sands and “Fighting Fire With Fire”

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

See this item, by Kevin Libin, writing for National Post: Yogourt fuels oil-sands war.

Here’s what is apparently intolerable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement that compares the consistency of tailings ponds to yogourt.

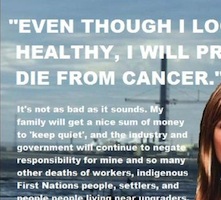

Here’s what is evidently acceptable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement warning that a young biologist working for Devon Energy named Megan Blampin will “probably die from cancer” from her work, and that her family will be paid hush money to keep silent about it….

It’s worth reading the rest of the story to get the details. Basically, the question is about the standards that apply to advertising by nonprofit or activist groups like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace. But it’s also more specifically about whether it’s OK for such groups to get personal by including in their ads individual employees of the companies they are targeting.

A few quick points:

- Many people think companies deserve few or no protections against attacks. Some people, for example, think companies should not even be able to sue for slander or libel. Likewise, corporations (and other organizations) do not enjoy the same regulatory protections and ethical standards that protect individual humans when they are the subjects of university-based research. Corporations may have, of necessity, certain legal rights, but not the same list (and not as extensive a list) as the list of rights enjoyed by human persons. So people are bound to react differently when activist groups attack (or at least name) individual human persons, as opposed to “merely” attacking corporations.

- Complicating matters is the fact that the original ads (by Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, or CAPP) themselves featured those same individual employees. So the employees had presumably already volunteered to be put in the spotlight. But of course, they volunteered to be put in the spotlight in a particular way.

- For many people, the goals of the organizations in question will matter. So the fact that Greenpeace and the Sierra Club are trying literally to save the world (rather than aiming at something more base, like filthy lucre) might be taken as earning them a little slack. In other words, some will say that the ends justify the means. On the other hand, the particular near-term goals of those organizations are not shared by everyone. And not everyone thinks that alternative goals (like making a profit, or like keeping Canadians from freezing to death in winter) are all that bad.

- Others might say that, being organizations explicitly committed to doing good, Greenpeace and the Sierra Club ought to be entirely squeaky-clean. If they can’t be expected to keep their noses clean, who can? On the other hand, some might find that just a bit precious. Getting the job done is what matters, and it’s not clear that an organization with noble goals wins many extra points for conducting itself in a saintly manner along the way.

(I’ve blogged about the tar sands and accusations of greenwashing, here: Greenwashing the Tar Sands.)

—

Thanks to LW for sending me this story.

CSR Advice for Students

I was recently interviewed for a student-oriented CSR project called “Citizen Act.”

I was recently interviewed for a student-oriented CSR project called “Citizen Act.”

Here’s the (public) Facebook page featuring the interview: Interview of Chris MacDonald, a Business Ethics Specialist

(Citizen Act is a “training game which trains students in the responsible banking practices of tomorrow.” It’s sponsored by Société Générale, a European financial services company.)

The interview is partly about my own career path, but also touches on my critique of CSR, as well as some stuff about the key obstacles for ethics/CSR, and my advice to students interested in this area. Here’s a snippet:

According to you, what are the main obstacles in the development of Business Ethics? Are there any cultural limitations? Any lack of resources or will?

I think the main obstacle is the complexity of organizations. Large, complex organizations exist for good reasons: they have the potential to be enormously productive and highly efficient. But they pose a challenge, both for internal control (by managers trying to implement a code of ethics, for example) and for external control (by regulators and ‘civil society.’)

The final bit is about my advice for students:

Would you have a message to deliver to students who are taking part in CITIZEN ACT?

My message would be to stay passionate, but to remember that being passionate about a topic like this is only the beginning. You need above all to use your brain, because our passions may run in different directions. Beyond that, avoid being either gullible or cynical about business. The world of commerce is enormously important for human well-being. Markets and the businesses that populate them do an enormous amount of good — our challenge is to figure out the best ways to conduct business so that it can stay competitive with the fewest possible negative side-effects.

Comments (21)

Comments (21)