Archive for the ‘decision-making’ Category

Is The Customer the Enemy?

Earlier this week I blogged about the intersection between customer service, ethics, and public relations. I pointed out that when the occasional grouchy remark turns into a pattern of disrespect, customer service becomes a question of ethics, and — in an age of social media — a potential PR nightmare.

But this raises a bigger question about the nature of the relationship between a business and its customers. Is the relationship between buyer and seller appropriately thought of as an adversarial one or a cooperative one? Ethically, is it right for a company to think of customers as friends or foes?

There are intuitive reasons on both sides. On one hand, buyer and seller have a shared interest in ‘doing the deal.’ They typically want to do business with each other, and both benefit from the transaction. On the other hand, every dollar a buyer saves is a dollar lost from the seller’s point of view. Every buyer wants a low price and every seller wants a high price, so the conflict is built right in.

We can name at least four different approaches to arriving at an answer to this question.

We might try looking at the question from the point of view of everyday ethics: people are people, and we should treat them honestly and with respect regardless of who they are. If fairness is good, then we should promote fairness in commercial transactions, just as we do in other areas of life. And that requires that buyer and seller at least see each other as equals. They don’t have to adopt a cooperative stance, but neither should they be adversarial.

We could instead take an economic approach. From an economic point of view, the interaction between buyer and seller is best understood as a ‘mixed motive’ game. In other words, it’s a game in which the players’ respective rankings of possible outcomes partly coincide and partly diverge. Both players would rather do a deal than not do a deal, but they disagree over what the best deal would be. If you’re in such a game, you should adopt an attitude that is neither fully cooperative nor fully adversarial. Unless, of course, displaying one of those attitudes moves the deal in your direction.

Third, we might think about this from the point of view of social conventions. It may well be that in certain cultures it is traditional (and perhaps widely accepted) that buyers and sellers treat each other as adversaries. And perhaps in certain other cultures it is traditional (and expected) that buyers and sellers will treat each other in a more convivial way. There are likely even individual industries typified by one or the other of those conventions. Doctors, for instance, are trained (and incentivized) to adopt a collaborative approach to their patients. Some stock brokers have notoriously adopted an adversarial approach to their clients.

Finally, we might think of this question from the point of view of corporate strategy. In other words, whether you think of your customers as friends or enemies — whether you adopt a collaborative or instead competitive attitude to them — might be a question of what kind of company you want to be. Some companies thrive on aggressive sales tactics; others thrive on a softer, more relationship-driven approach. Seen from this point of view, there’s no single, general answer to the question. Each firm needs to answer it for itself.

Regardless of how you frame the question, and regardless of the answer you arrive at, the attitude your company adopts towards customers is bound to become well known, especially in an era in which reputation spreads via Facebook and Twitter. Seller beware!

University Frosh Rape Chant Poses Leadership Challenge

Last week, a scandal sprouted on Canada’s east coast, when it was discovered that part of Frosh Week activities at Saint Mary’s University (SMU), in Halifax, included the chanting of a song promoting the sexual assault of underage girls. The news broke shortly after a video of the chant was posted online. Condemnation was broad and swift. Some were angry at the students. Others were angry at university administrators. Others simply lamented the sad state of “youth today” and the perpetuation of the notion that it is OK to glorify rape.

As it happens, I taught for about a decade in SMU’s Philosophy Department; I still have friends who teach there. I know some of the administrators involved in this case, and have more than a little affection for the place, generally.

My own particular scholarly interest in this case, though, has to do with the ethics of leadership. I think the events described above provide a good case-study in the ethics of leadership. That’s not to say that it is an example of either excellent or terrible leadership. But rather, that it’s a case that illustrates the challenges of leadership, and an opportunity to reflect on the ethical demands that fall on leaders in particular, as a result of the special role they play.

Two key leaders were tasked with handling the SMU situation. One was Jared Perry, President of the Saint Mary’s University Student Association. Perry has now resigned. Reflecting on his error, Perry said “It’s definitely the biggest mistake I’ve made throughout my university career and throughout my life.” The other leader is SMU president Colin Dodds. For his part, Dodds has condemned the chant and the chanters, and has launched an internal investigation and a task force.

A leader facing a crisis like this needs to balance multiple objectives.

On one hand, a leader needs to safeguard the integrity and reputation of the organization. Of course, just how to do that can be a vexing question. Do you do that by effecting a ‘zero tolerance’ policy, or by a more balanced approach? Do you focus on enforcement, or education?

A leader also needs to deal appropriately with the individuals involved. In this case, that means offering not just critique (or more neutrally, “feedback”) to the students involved, but also offering compassion and advice in the wake of what everyone agrees is a regrettable set of circumstances. In particular, a situation like this involves a “lead the leaders” dynamic. It is an opportunity for university leaders to teach something specifically about leadership to the student leaders involved. It is also, naturally, yet another opportunity for university leaders to learn something about leadership themselves; unfortunately, that lesson must take the form of learning-by-painfully-doing.

Finally, a leader needs to be responsive to reasonable social expectations. In this case, those expectations are complex. On one hand, society wants institutions entrusted with educating the young provides a suitably safe setting, and arguably one that fosters the right kinds of enculturation. On the other hand, society wants — or should want — universities to be places where freedom of speech is maximized and where problems are addressed through intellectual discourse. Indeed, my friend Mark Mercer (in SMU’s philosophy department) has argued that what the university ought to demonstrate, in such a situation, is its commitment to intellectual inquiry and to the idea that when someone uses words we disagree with, we should respond not with punishment but with open discussion and criticism.

Balancing those objectives is a complex leadership challenge. And there’s no algorithmic way to balance such competing objectives. But one useful way to frame the leadership challenge here is to consider the sense in which, in deciding how to tackle such a challenge, a leader is not just deciding what to do. He or she is also deciding what kind of leader to be, and what kind of institution he or she will lead. Each such choice, after all, makes an incremental difference in who you are. It is at moments like this that leaders build institutions, just as surely as if they were laying the bricks themselves.

The Business Significance of the ‘Trolley Problem’

There’s a famous philosophical thought experiment known as “the Trolley Problem.” It goes roughly like this. Imagine one day you see a trolley — the famous San Francisco variety, or something more like a Toronto streetcar — hurtling along its track. The driver is incapacitated, and the trolley is bearing down on 5 people, mysteriously unconscious on the track. You happen to be standing next to a switch, which can divert the trolley onto a different track. But lying on this other track is another unconscious person.

There’s a famous philosophical thought experiment known as “the Trolley Problem.” It goes roughly like this. Imagine one day you see a trolley — the famous San Francisco variety, or something more like a Toronto streetcar — hurtling along its track. The driver is incapacitated, and the trolley is bearing down on 5 people, mysteriously unconscious on the track. You happen to be standing next to a switch, which can divert the trolley onto a different track. But lying on this other track is another unconscious person.

So assuming (as the philosophy professor insists you must) that you don’t have time to haul any of the various unconscious persons off the tracks, your choice is effectively this: should you divert the trolley, thereby killing one person, or do nothing, and allow 5 people to die?

The puzzle is intended to get you to think about what’s more important: promoting good outcomes (fewer deaths instead of more) or sticking to cherished principles (like the principle that you should not cause the death of an innocent person). It makes for a fun and often fruitful classroom discussion.

But as a model of real-life ethical decision-making, the trolley problem is pretty bad. Seldom does life present you with two cut-and-dried options, neatly packaged by your philosophy professor. As Caroline Whitbeck points out, real life isn’t a multiple-choice test. In real life — in business, for example — ethical problem solving is more like a design problem: you need to design the options, before you get to choose among them.

But the trolley problem can still serve as a useful starting point for talking about business ethics. The key is to ask the right questions. Here are a handful of questions designed to make the trolley problem relevant to business ethics. Each, of course, requires a bit of mental translation. We are not, after all, primarily interested in actual trolleys.

1) Does your business need a policy for situations like this? Is your business one in which trolley-problem-like dilemmas come up often? Are employees often faced with situations that require them to trade off outcomes against principles? If so, do existing policies tell them how to deal with such dilemmas appropriately?

2) Is there anything you can do to prevent situations like this from happening in the first place? One of the key characteristics of the trolley problem is that it’s a lose-lose situation: either you kill an innocent person, or you allow several people to die. It’s worth asking (especially if such problems are common; see #1 above) whether there’s something you can do to avoid such situations so that you don’t have to deal with them at all.

3) What kind of corporate culture have you fostered, and how will that culture push people one way or the other in such situations? The trolley problem is a true dilemma, and reasonable people can disagree about it. But what about situations in which you can throw a switch and kill 5 people (metaphorically, at least) in order to save one? And what if that one isn’t a person, but is your company’s bottom line? Will your company’s culture encourage employees to put short-term profit ahead of all other considerations

4) Will people in your organization recognize situations akin to the trolley problem as being ethical problems in the first place? Or will they make the decision on purely technical grounds? Will they see past the fact that flipping switches is, you know, their job? Or past the fact that hey, the trolley has to run on time, and we always flip this switch that way at this time of day?

5) Finally, if the decision were being made by a team, or members of a hierarchy, rather than by an individual, would members feel empowered to speak their mind if they felt the team, or their boss, was making a bad decision?

Philosophical puzzles like the trolley problem become famous for a reason. They get at something deep. And they can provide fruitful fodder for discussion as part of corporate ethics training. The core of a great discussion is there: you’ve just got to know the right questions to ask.

Cream, Sugar, and Choice

Is the customer always right? Is it more important to protect consumers, or to give them options and let them choose? This is a real-life dilemma that was posed to me recently. I’ve changed the names and some other details in what follows, but the basic dilemma is real.

Abe and Ben are starting a coffee shop together. Situated in a trendy neighbourhood, the shop will feature high-quality, fair-trade, organic coffees and a range of gourmet pastries from a local bakery. They’re in the process now of deciding on their menu, and on smaller details like the condiments (sugar, cream, etc.) that will be available for patrons. It is this latter issue that has brought Abe and Ben into conflict.

Abe contends that the only condiments they should provide are cane sugar, organic milk, and soy milk. Abe wants no white sugar or artificial sweeteners. After all, he says, the health of our customers matters, and white sugar and artificial sweeteners are unhealthy.

Ben says, Look, the customer is king. Some will appreciate cane sugar, sure, but some want the white sugar they grew up with, and some diet-conscious folks will want zero-calorie artificial sweeteners, and we should give them what we want. Who are we to tell them what to do?

So who is right?

I would say choice is a good thing. To the best of my knowledge, the evidence is very weak that “other” condiments are bad for you (especially in the relevant, tiny quantities). For that matter, if Abe is that concerned about his customers’ health, he should argue for not serving sugar at all. There’s plenty of evidence that that is bad for you. As a scientist friend of mine puts it: there’s much more evidence that sugar is bad for you than there is that artificial sweetener is bad for you.

Of course, if Abe and Ben decide to make “100% natural,” or something like it, a part of their branding — as many companies do — then it makes sense to offer only condiments that are consistent with that ethos. But there’s no reason to think of that as a more ethical policy.

Feeding the Hand that Bites You

Two stories surfaced this week about companies faced with handing out prizes to businesses whose interests were contrary to their own.

One company graciously gave credit where credit was due. The other declined to do so. Is it ethical to decline to feed the hand that bites you?

The company that declined to recognize another’s achievements was CBS, which forced subsidiary CNET to alter the results of the ‘Best of CES‘ award it gives out after the annual consumer electronics show. CNET’s editors had intended to give top honours to the Dish Network’s “Hopper”, a set-top box that allows viewers to skip commercials. As reported here, CBS has been in a legal battle with the Dish Network over the Hopper, which CBS sees as threatening its stream of ad revenue. The CBS v. Dish lawsuit was cited by CBS as the reason for withdrawing the Hopper from consideration for the CNET award.

And on the other hand: the company that went ahead and gave an award to a competitor was USA Today. The newspaper, you see, had run a contest to reward excellence in print advertising. And the winner, ironically, was Google — the search giant that is cited as one of the key reasons why print advertising is on the decline.

Because both US Today and CNET are media outlets, the most obvious question here has to do with editorial independence. Media companies are in a special situation, ethically. Most of them need to earn a living, but most of them also proclaim a public-service mission, and along with that mission goes a commitment to journalistic independence. Of course, giving out awards is closer to a news outlet’s editorial function, and editorial content has never been as cleanly divorced from commercial concerns as pure news is supposed to be. But if awards handed out by media outlets are to mean anything, they need to remain pretty independent, and meddling by a parent company is bound to cast doubt on editorial independence pretty generally. CBS’s meddling in the CNET’s award has already led one reporter, Greg Sandoval, to resign.

Setting aside the media ethics angle, we might appeal to basic principles of fairness. If you hold a contest, then all eligible contestants deserve a fair shake. If you don’t want to allow your enemies to compete, it’s probably fair if you state that transparently up front. But, other things being equal, everyone deserves an equitable opportunity to compete and win. That’s basic ethics.

Then again, it’s worth reminding ourselves that business is fundamentally adversarial, and the rules that apply in adversarial domains just aren’t going to be the same as those that apply in cozier sorts of interaction. So, in the present case, we might say that the need to observe basic fairness in the treatment of contestants is legitimately overridden by the right not to harm your own interests by advertising a competitor’s product.

But the right to protect your company’s interests needs to be balanced against the kind of signal you send when you take a stand or announce a policy in this regard. What has CBS told us about itself as a company? What kind of outfit has USA Today shown itself to be? This isn’t just a matter of PR; it’s a matter of who CBS and USA Today are as companies. In many respects, you are what you are perceived to be, and what you are perceived to be reflects the actions you take in public.

Customizing Ethical Products

So-called “ethical” products are in the news again. This time, the controversy is over whether the fairtrade movement should expand to include certification of large farms.

A controversy like this serves to highlight the complexity of the notion of an “ethical” product. After all, any product has many different characteristics, and hence many different dimensions of ethical concern. Just for starters, two food products of the same kind (say, two different brands of coffee) might vary in terms of whether they are FairTrade certified or not, whether they are organic or not, whether they are from countries with bad human-rights records, and so on. So the choice we face isn’t just between the ethical brand and the “other” brand; it might well be between two brands with different combinations of more, or less, ethical characteristics.

So here’s a thought experiment. Imagine a world in which mass customization technology make it possible for you, by purchasing online, to hyper-customize the products you buy, according to various ethical characteristics. Imagine you could choose, with a click of your mouse, any or all of a range of characteristics. And to make things more interesting (and likely more realistic) let’s say that each additional characteristic you ask for implies some additional cost. After all, some “ethical” production processes are costly, and some certification schemes are costly. So let’s imagine, say, that each additional ethical characteristic you opt for results in a modest 2% increase in the price of the product.

Given the opportunity to buy such customized products, which ethical characteristics would you choose to pay for?

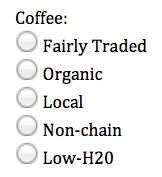

Consider, for example, what you would choose faced with a website that let you order coffee and gave you the following options:

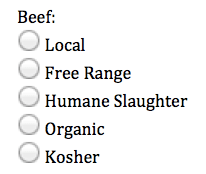

Or imagine being able to buy beef and to select from among the following characteristics:

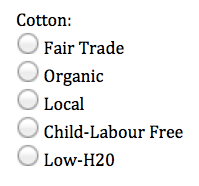

Or again, imagine being offered the following choice with regard to the cotton from which your newly-tailored shirt is to be made:

This thought experiment raises several questions. For you, the consumer, it raises the question of which combination of ethical values you really want — and would be willing to pay for — in your purchases. For purveyors of “ethical” consumer products, it first raises doubts about the term itself, and about how confident companies can be that they’ve already identified “the” characteristics that make up an ethical product. Consider the light this sheds on the case of so-called “ethical veal,” as discussed in a recent story from the Guardian. Sure, the veal referred to in that story is ethically better in at least one way. But have the people selling it cognizant of the range of characteristics that different people regard as essential to making a food product truly ethical?

Of course, the shopping scenario imagined above is science fiction for now. You can buy customized shoes online, and customized chocolate bars, but as far as I know foods customized ethically are not yet on sale. If they were, would that make the choice faced by ethical consumers easier, or harder?

Mobile Phones, Airlines, and Long-Term Contracts

Contracts are an essential part of modern business. Contracts make business partners more reliable, fostering trust beyond the limits of basic human trustworthiness and a firm handshake. Indeed, one of the main ways in which all modern economies treat corporations as ‘persons‘ under the law is evidenced by the fact that corporations can sign, and be bound by the terms of, contracts. Contracts provide uniformity and security. Contracts can also be contentious, hence the evolution of an entire branch of law known as Contract Law.

Sometimes, one party or another comes to regret signing a contract, especially long-term contracts. Two such cases have been in the news recently.

One story involves consumers regretting signing contracts, in particular mobile phone contracts. Here in Ontario, a bill has been introduced that attempts to improve mobile phone contracts for consumers, including making it easier for consumers to end contracts without massive penalties. It turns out that consumers like the low, low phone prices made possible by long-term contracts, but aren’t so fond of actually paying the full price of such contracts. And most people, I suspect, sympathize with the consumer here rather than with the phone companies who want to see their contracts honoured.

The other story about contracts flips that one on its head. It’s a story about frequent fliers who bought tickets — essentially, signed contracts — giving them unlimited first-class flying on American Airlines. But this time, it’s not the consumer who came to regret the deal, but rather the company. You see, American, when they sold these tickets years back (for prices in the quarter-million dollar range) didn’t foresee the ways in which some customers would use — and perhaps abuse — the privileges those tickets embodied. A handful of super-frequent fliers are using their lifetime tickets so intensively that they’re each costing the airline something like a million dollars a year.

Of course, this story is unlikely to generate much sympathy. Most people dislike big corporations like American Airlines, and almost everyone has reason to gripe about airlines in particular. Tough luck, suckers! And after all, a big corporation like that can afford it, right? Well, no, as it turns out profit margins in that industry are vanishingly thin, and even negative in some years. (In related news American recently asked a bankruptcy court to nullify its contracts with various labour unions.)

The more general question here has to do with whether we should protect people (and companies) from the results of their poor decisions. One set of reasons has to do with protecting the interests of persons: as a society, we have duty to protect each other at least to some extent. And in the commercial domain the consequences of certain choices can be unclear. This is a reason for laws encouraging clarity of contract, if not provisions for voiding them altogether.

Another set of reasons has to do with the social benefits, both of contracts and of occasionally voiding them. Contracts are designed to reduce the risk of doing business; but the act of signing a contract also involves taking a risk, namely the risk that things will turn out differently than you had expected, and that holding up your end of the bargain will end up being disadvantageous. And we want people, and companies, to take those kinds of risks; without them, commerce (and hence our standard of living) would return to stone age levels. So we may in some situations want to provide safety nets to make such risk-taking reasonable. Whether we have the moral imagination needed to see the full range of costs and benefits to the full range of relevant parties is another matter.

Wal-Mart Bribery and Bad Examples

This is the third in a series of postings on the bribery scandal at Wal-Mart de Mexico and its parent company, Wal-Mart Stores, Inc.

I’ve already dealt with why bribery is so seriously problematic in general. But let’s look here at why this particular instance of bribery (or pattern of bribery, really) by this particular company is especially problematic.

It goes without saying that the bribery that allegedly took place at Wal-Mart de Mexico is a wonderful example of lousy “tone at the top.” Eduardo Castro-Wright, who was CEO of Wal-Mart de Mexico during the bulk of the wrongdoing, is centrally implicated, as are senior people at Wal-Mart Stores, Inc., including CEO Mike Duke. How on earth can they now hope to exercise any ethical leadership? Clearly, they can’t, and that’s why in my opinion they both need to resign or be fired.

But the bad example set by this set of behaviours goes well beyond the walls of Wal-Mart itself.

Wal-Mart is an industry leader, taken by many as an example of how business ought to be done. The signal sent here is particularly corrosive with regard to doing business in Mexico. Mexico clearly has its problems with corruption. But there’s a self-fulfilling prophesy in this regard. If companies see Mexico as a place where bribery is necessary, they’re sometimes going to offer bribes to public officials who, in turn, will come to expect bribes. And if Wal-Mart, of all companies, says it can’t compete effectively in the Mexican market without engaging in that sort of thing — well, the lesson for merely-mortal companies is clear. If Wal-Mart can’t thrive there by playing by the rules, who can?

Think also about Wal-Mart’s supply chain, and the example this behaviour sets for the thousands of companies that supply Wal-Mart, directly or at one or more steps removed, with the goods it sells. Wal-Mart is notoriously tough on its suppliers, insisting on lower and lower prices and higher and higher levels of efficiency. But naturally — naturally! — Wal-Mart wants its suppliers to do all that within the limits of the law, right? Or at least that has to be the company’s official policy. But now, what are suppliers to think? With the revelation of Wal-Mart’s own lawless behaviour, the message to suppliers — thousands and thousands of them — is that getting the job done matters more, and that the ends justify the means.

OK, but won’t the fact that the Wal-Mart executives involved got caught also serve as an example? Well, perhaps. But that depends in part on what action is taken by law enforcement agencies and by the company’s own Board. I strongly suspect that decision-makers at a lot of companies will continue to fall prey to the cognitive illusion that so often facilitates wrongdoing of all kinds: “I’m too smart to get caught.”

So Wal-Mart has provided a clear example in terms of the benefits of bribery, and only a weak one in terms of the costs. Wal-Mart’s shareholders lost $10 billion this past Monday, in the wake of these revelations. But I fear the real impact of the scandal will be much bigger, and broader.

Financial Advice, Competency, and Consent

I blogged recently on a California case about an insurance agent who was sentenced to jail for selling an Indexed Annuity — a complex investment instrument — to an elderly woman who may have been showing signs of dementia. I argued that giving investment advice is just the sort of situation in which we should expect professionals to live up the standard of ‘fiduciary’, or trust-based duty. An investment advisor is not — cannot be — just a salesperson.

But asserting that investment advisors have fiduciary duties doesn’t settle all relevant ethical questions. It settles how strong or how extensive the advisor’s obligation is; but it doesn’t settle just how the financial advisor should go about living up to it.

The story alluded to above again serves as a good example of that complexity. How should a financial advisor, in his or her role as fiduciary, handle a situation in which the client shows signs of a lack of decision-making competency? Sure, the advisor needs to give good advice, but in the end the decision is still the client’s. How can an advisor know whether a client is competent to make such a decision?

In the field of healthcare ethics, there is an enormous literature on the question of ‘informed consent,’ including the conditions under which consent may not be fully valid, and the steps health professionals should take to safeguard the interests of patients in such cases.

The way the concept is explained in the world of healthcare ethics, informed consent has three components, namely disclosure, capacity and voluntariness. Before a health professional can treat you, he or she needs to disclose the relevant facts to you, make sure you have the mental and emotional capacity to make a decision, and then make sure your decision is voluntary and uncoerced. And the onus is on the professional to ensure that those three conditions are met. But there’s really nothing very special about healthcare in this regard. Selling someone an Indexed Annuity isn’t as invasive, perhaps, as sticking a needle in them, but it often has much more serious implications.

Of the three conditions cited above — disclosure, capacity and voluntariness — disclosure is of course the easiest for those in the investment professions to agree to. Of course you need to tell your client the risks and benefits of the product you’re suggesting to them. But of course, many financial products have an enormous range of obscure and relatively small risks — must the client be told about those, too? There’s only so much time in a day, and most clients won’t care about — or be able to evaluate — those tiny details.

Voluntariness might also be thought of as pretty straightforward. A client who shows up alone and who doesn’t seem distressed is probably acting voluntarily, and it’s unlikely that we want investment professionals poking around our personal lives to find out if there’s a greedy nephew lurking in the background and badgering Aunt Florence to invest in penny stocks.

What about capacity? That’s the tough one, the one implicated in the court decision alluded to above. Notice that in most areas of the market, no one tries to assess your capacity before selling to you. I bought a car recently, and all the salesperson cared about was a driver’s licence and my ability to pay. No one tried very hard to figure out if I was of sound mind — beyond immediate appearances — and hence able to make a rational purchase.

Investment professionals do typically recognize a duty to ensure the “suitability” of an investment, and presumably whether an investment is suitable depends on more than just the client’s financial status. It also depends in part upon whether the client is capable of understanding the relevant risks. Being a true professional and earning the social respect that goes with that designation is going to require that financial advisors of all sorts adopt a fiduciary view of their role. That means learning at least a bit about the signs of dementia and other forms of diminished capacity. It also means knowing how and when to refer a client to a relevant health professional. Finally and most crucially, it means putting the client first — solidly and entirely first — and hence being willing to forego a sale when that is clearly the right thing to do.

Apple: The Ethics of Spending $100 Billion

What’s the best thing to do with a hundred billion dollars? Apple — the world’s richest company — gave its answer to just that question, when it announced yesterday how it will spend some of the massive cash reserve the company has accumulated.

Of course, spending the whole $100 billion was never on the agenda. The company needs to keep a good chunk of that money on-hand, for various purposes. Then there’s the fact that a big chunk of it is currently held by foreign subsidiaries, and bringing it back to the US to spend it would require Apple to pay hefty repatriation taxes. But any way you slice it, Apple has a big chunk of cash to spend, and so its Board faces some choices.

In the abstract, there are lots of things one could do with that much money. Financial analysts had rightly predicted that Apple company would decide to pay out a dividend (for the first time since 1995). Some were predicting bolder moves, like buying Twitter (which would use up a mere $12 billion). But what could Apple have done with that much money, aside from narrow strategic moves?

The money could have, in principle, been spent on various charitable projects. That amount of money could also do a lot towards helping developing countries combat and adapt to climate change. Or it could revolutionize the American education system. Closer to home, the company could spend a bunch on improving working conditions at its factories in China, conditions for which the company has been widely criticized. All of these, and many more, are (or rather were) among the possibilities.

But business ethics isn’t abstract; Apple’s Board faced a concrete question. And the Board has ethical and legal obligations to shareholders. Those aren’t its only obligations, but once workers are paid, warranties are honoured, expenses are covered, and relevant regulations are adhered to, the main remaining obligation is to shareholders.

Now, there’s a significant strain of thought that says that a company’s managers (and its Board) are not there just to serve the interests of shareholders, but also to carry out shareholders’ obligations. So, if you believe that Apple shareholders have an obligation to fight climate change or to promote education or to improve conditions for workers, then maybe it makes sense to think that the company ought to help shareholders to act on that obligation. But keep in mind that Apple’s shareholders are a rather amorphous group. Shares in corporations change hands incredibly frequently, and the interests and obligations of shareholders vary significantly, so a Board ‘represents’ shareholders (or acts as their agent) only in a rather abstract sense.

The alternative, of course, is for Apple’s Board to give itself some leeway, forget about what shareholders’ collective obligations might be, and go back to thinking abstractly about what to do with that big pile of cash. They can simply decide whether the shareholders’ financial interests outweigh their collective obligation to do some good with that money, and simply decide which of the various worthy causes it should go to. But of course, lots of people are rightly uncomfortable with the idea of well-heeled corporate boards arrogating to themselves that kind of power. The question for discussion, then, is this. Which is the greater evil? For corporations not to step up to the plate and contribute to social objectives, or for corporate leaders to presume to spend vast sums of money as if it were their own?

Comments (5)

Comments (5)