Archive for the ‘ethics’ Category

Ethics of Insider Trading

“Insider trading” is one of those phrases that most adults have heard (at least on the nightly news), but that relatively few understand. (Perhaps the most famous case: Martha Stewart was originally charged with insider trading in the ImClone case.) I imagine few people even know what it really refers to. Well, it refers to situations in which corporate “insiders” (executives, directors, etc.) buy or sell their company’s stock on the basis of significant corporate information that is not available to the investing public more generally. (For more details, see the Wikipedia page on insider trading.)

But even if we don’t all know just what insider trading is, we all know insider trading is bad, and must be stopped. Right? But it’s hard to stop something that’s hard to define. In that regard, see this nice piece by Steve Maich, Editor of Canadian Business: “Chasing our tails while we chase insider trading.”

In case you hadn’t noticed, we are in the midst of a crackdown. Or rather, another crackdown. The crime du jour is an old favourite: insider trading….

There are obvious benefits to these shows of regulatory force. Seeing hedge fund managers and lawyers in handcuffs not only produces a nice dopamine rush, it’s also meant to demonstrate the integrity of the capital markets. But the costs are frequently overlooked. Like most crackdowns, this one seems likely to deepen cynicism, erode confidence and lob more grenades at shell-shocked markets….

Maich is undertandably cynical about these enforcement efforts:

Despite the periodic efforts of regulators to stamp it out, insider trading runs as rampant as ever, and that isn’t going to change. This is in part because it’s notoriously difficult to prove, but also because we have never definitely solved the fundamental puzzles at the heart of this supposed crime….

It’s worth adding that there is genuine disagreement over just why insider trading is unethical. (Some people even think it’s not unethical at all, because the executive who trades on “inside” information ends up indirectly bringing that information to the market, rendering the latter more efficient.) And if we’re not entirely sure why it’s unethical, it makes it that much harder to figure out in which cases it’s unethical.

The only scholarly article I’ve read on the ethics of insider trading is by Jennifer Moore, and is called “What Is Really Unethical About Insider Trading?”* Moore looks at a number of arguments against insider trading — arguments rooted in fairness, in property rights, and in the risk of harm to investors — and finds most of them lacking. Moore ends up arguing — plausibly, in my view — that the real reason insider trading is unethical is that it jeopardizes the fiduciary relationships that are central to business. If insider trading were permitted, that would put corporate insiders in a conflict of interest. Basically, the interests of corporate insiders would stop being well-aligned with the interests of the shareholders they are supposed to serve. And if the interests of corporate insiders aren’t aligned with the interests of shareholders, then people are much less likely to be willing to buy shares (i.e., to invest) in companies. And that wouldn’t be good for the firm, for its shareholders, or for society in general.

—–

*Jennifer Moore, “What Is Really Unethical About Insider Trading?” Journal of Business Ethics, Volume 9, Number 3, 171-182.

Greenpeace, Tar Sands and “Fighting Fire With Fire”

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

Do higher standards apply to advertising by industry than apply to advertising by nonprofits? Is it fair to fight fire with fire? Do two wrongs make a right?

See this item, by Kevin Libin, writing for National Post: Yogourt fuels oil-sands war.

Here’s what is apparently intolerable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement that compares the consistency of tailings ponds to yogourt.

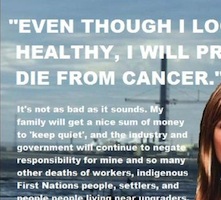

Here’s what is evidently acceptable to certain environmental groups opposed to Alberta’s oil sands industry: an advertisement warning that a young biologist working for Devon Energy named Megan Blampin will “probably die from cancer” from her work, and that her family will be paid hush money to keep silent about it….

It’s worth reading the rest of the story to get the details. Basically, the question is about the standards that apply to advertising by nonprofit or activist groups like the Sierra Club and Greenpeace. But it’s also more specifically about whether it’s OK for such groups to get personal by including in their ads individual employees of the companies they are targeting.

A few quick points:

- Many people think companies deserve few or no protections against attacks. Some people, for example, think companies should not even be able to sue for slander or libel. Likewise, corporations (and other organizations) do not enjoy the same regulatory protections and ethical standards that protect individual humans when they are the subjects of university-based research. Corporations may have, of necessity, certain legal rights, but not the same list (and not as extensive a list) as the list of rights enjoyed by human persons. So people are bound to react differently when activist groups attack (or at least name) individual human persons, as opposed to “merely” attacking corporations.

- Complicating matters is the fact that the original ads (by Canadian Association of Petroleum Producers, or CAPP) themselves featured those same individual employees. So the employees had presumably already volunteered to be put in the spotlight. But of course, they volunteered to be put in the spotlight in a particular way.

- For many people, the goals of the organizations in question will matter. So the fact that Greenpeace and the Sierra Club are trying literally to save the world (rather than aiming at something more base, like filthy lucre) might be taken as earning them a little slack. In other words, some will say that the ends justify the means. On the other hand, the particular near-term goals of those organizations are not shared by everyone. And not everyone thinks that alternative goals (like making a profit, or like keeping Canadians from freezing to death in winter) are all that bad.

- Others might say that, being organizations explicitly committed to doing good, Greenpeace and the Sierra Club ought to be entirely squeaky-clean. If they can’t be expected to keep their noses clean, who can? On the other hand, some might find that just a bit precious. Getting the job done is what matters, and it’s not clear that an organization with noble goals wins many extra points for conducting itself in a saintly manner along the way.

(I’ve blogged about the tar sands and accusations of greenwashing, here: Greenwashing the Tar Sands.)

—

Thanks to LW for sending me this story.

Ethics and Stupidity

Why do people do bad things? It’s an ancient question. Certainly, some people do bad things simply because they are bad people. Psychopaths and sociopaths exist, though thankfully they are very few. Whether those few should be classified as “evil,” or as “mentally ill,” or both, is not clear to me. Either way, they certainly have the capacity to do evil. But sometimes, surely — maybe quite often — people do bad things stupidly, rather than out of evil intent. Sometimes, as I’ve blogged before, people do bad things because they allow themselves to use invalid excuses. It’s likely that some people know (in their heart of hearts) that they’re using lame excuses. But probably some people sincerely believe those excuses, and simply don’t understand that their reasoning is flawed.

Why do people do bad things? It’s an ancient question. Certainly, some people do bad things simply because they are bad people. Psychopaths and sociopaths exist, though thankfully they are very few. Whether those few should be classified as “evil,” or as “mentally ill,” or both, is not clear to me. Either way, they certainly have the capacity to do evil. But sometimes, surely — maybe quite often — people do bad things stupidly, rather than out of evil intent. Sometimes, as I’ve blogged before, people do bad things because they allow themselves to use invalid excuses. It’s likely that some people know (in their heart of hearts) that they’re using lame excuses. But probably some people sincerely believe those excuses, and simply don’t understand that their reasoning is flawed.

“Hanlon’s Razor” is the name for an adage attributed to one Robert J. Hanlon. It says the following:

Never attribute to malice that which is adequately explained by stupidity.

It’s a good rule of thumb, not least because it is so often true that bad outcomes owe more to poor decision-making than they do to evil intent.

Of course, if what we’re really interested in is why bad things happen, attributing it to stupidity rather than malice just pushes the question down one level. If so many people act stupidly, why?

There are at least 3 kinds of situations in which dumb things happen:

- Some dumb moves are made by people who, well, are not that bright. The truth is that people have different levels of ability. We don’t all have equally-good judgment, and we’re not all equally good at foreseeing the consequences of our actions. In a corporate context, good hiring practices are supposed to weed out the untalented. But talent pools are always limited. And remember: screwups can in principle occur anywhere within a corporate hierarchy, so there’s no position so unimportant that a company can simply afford to fill it poorly.

- Some dumb moves are made by people — maybe even smart people — who lack the relevant skills. In some cases, that may mean they lack the relevant technical skills. If you’re not an accountant, for example, you simply may not understand the consequences of certain kinds of bookkeeping decisions. But people can also lack the skills to assess, for example, the quality of their own arguments and thought processes. I teach a course on Critical Thinking, and believe me, people are not all equally good at spotting fallacious arguments or flawed patterns of thought. But it’s a skill-set that can be taught, and learned.

- Some “dumb” decisions get made as a result of one or another of a bunch of well-studied cognitive biases. Those biases — the subject of an enormous body of psychological literature — go by names like “anchoring,” and “confirmation bias” and “the framing effect,”. (Confirmation bias, for example, essentially means that we have a tendency to accept new evidence when it confirms what we already believe, and to reject new data that challenges our beliefs. It’s dangerous, and we all do it.) Basically, cognitive biases are a bunch of persistent, and generally faulty, trends in the way humans think. They are ways in which we are pretty consistently subject to patterns of error in our thinking. Alarmingly, these cognitive biases tend to apply to smart people, too, as well as to people with the kind of technical training that you might hope would help them avoid such biases.

(For a bit more on why individuals do dumb things, see this Wired piece on Why Do Smart People Do Stupid Things?)

So, there are lots of reasons why people — even smart people — end up doing dumb things. And sometimes those dumb things will have evil (or just bad) consequences. It’s worth understanding the difference between bad things that happen because someone did something bad, and bad things that happen because someone did something dumb, though in some cases the line will be pretty fuzzy.

And I suspect Hanlon’s Razor holds true of organizations just as it does for individuals, and maybe more so. So really, we need to distinguish between why individuals act stupidly, and why organizations do. That’s a topic for another day.

Why Privacy Matters

I have a short piece on privacy in the Fall/Winter 2010 newsletter of the Canadian Centre for Ethics & Corporate Policy.

In the intro to the article, I delve into just what privacy is, why it is that we value it in the first place:

Privacy, at its most basic, is about having a sphere of personal control from which others can be excluded at will. It refers not just to information, though that is certainly a key component of privacy. Privacy is also about freedom of action, action that is not hindered by the prying eyes of neighbours, governments, or corporations. The more such freedom we have, the more privacy we have….

In the second half, I discuss why it is that companies should think carefully about privacy. I note that it’s not just a question of protecting customers’ private information, though that is certainly important. It’s also worth considering that companies themselves tend to value privacy, and they ought to keep that in mind:

…when a company asserts its own privacy rights, it is in at least some cases thereby protecting the privacy of its clients, along with the rights of its shareholders. But the key point here is that when companies think about the value of privacy, they would do well to consider how much privacy also matters to them.

The newsletter also includes a commentary on privacy from Ontario’s Privacy Commissioner, a piece on privacy concerns in the hiring process, by lawyer Avner Levin, and an article on privacy law more generally by lawyer Christine Lonsdale. You can download the entire newsletter here: Management Ethics Newsletter.

Wikileaks, Credit-Card Companies, and Complicity

I was interviewed last night on CBC TV’s “The Lang & O’Leary Exchange” about Mastercard and Visa’s decision to stop acting as a conduit for donations to the controversial secret-busting website Wikileaks. [Here’s the show. I’m at about 15:45.] (For those of you who don’t already know the story, here’s The Guardian‘s version, which focuses on retaliation against Mastercard by some of Wikileaks’ fans: Operation Payback cripples MasterCard site in revenge for WikiLeaks ban. )

I was interviewed last night on CBC TV’s “The Lang & O’Leary Exchange” about Mastercard and Visa’s decision to stop acting as a conduit for donations to the controversial secret-busting website Wikileaks. [Here’s the show. I’m at about 15:45.] (For those of you who don’t already know the story, here’s The Guardian‘s version, which focuses on retaliation against Mastercard by some of Wikileaks’ fans: Operation Payback cripples MasterCard site in revenge for WikiLeaks ban. )

Basically, the show’s hosts wanted to talk about whether a company like Mastercard or Visa is justified in cutting off Wikileaks, and essentially taking a stand on an ethical issue like this.

Here’s my take on the issue, parts of which I tried to express on L&O. Now just to be clear, what follows is not intended to convince you whether you should be pro- or anti-Wikileaks. The question is specifically whether Mastercard and Visa, knowing what they know and valuing what they value, should support Wikileaks’s activities.

I think that, yes, Mastercard & Visa are justified in cutting off Wikileaks. And I don’t think that conclusion depends on arriving at a final conclusion about the ethics of Wikileaks itself. The jury is still out on whether the net effect of Wikileaks’ leaks will be positive or negative. Likewise it is still unclear whether Wikileaks’ activities are legal or not. And who knows? History may be kind to Wikileaks and its front-man, Julian Assange. The question is whether, knowing what we know now, it is reasonable for Mastercard & Visa to choose to dissociate themselves. I think the answer is clearly “yes.” The key here is entitlement: the secrets that Wikileaks is disclosing are not theirs to disclose. They don’t have any clear legal or moral authority to do so, and so Mastercard & Visa are very well-justified in declaring themselves unwilling to aid in the endeavour.

One question that came up in last night’s interview had to do with complicity. Is a company like Mastercard or Visa complicit in the activities of Wikileaks? The answer to that question is essential to answering the question of whether the credit card companies might have been justified in simply claiming to be neutral, neither endorsing nor condemning Wikileaks but merely acting as a financial conduit. I think the answer to that question depends on at least 3 factors.

- 1. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa actually endorse Wikileaks’ activities?

- 2. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa know about those activities? and

- 3. To what extent does Mastercard or Visa actually make Wikileaks’ activities possible? That is, what is the extent of their causal contribution? Do they play an essential role, or are they a bit player?

In terms of question #1, it’s worth noting the significance of the particular values at stake, here. Wikileaks stands for transparency and for publicizing confidential information. Visa and Mastercard stand for pretty much the exact opposite. Visa and Mastercard, like other financial institutions, are able to do business because so many people trust them with their financial and other personal information. And so the credit card companies are, of all the companies you can think of, pretty clearly among the least likely to be able to endorse Wikileaks’ tactics, whatever they think of the organization’s objectives.

It’s also worth noting the significance of the notion of “corporate citizenship,” here. That term is widely abused — sometimes it’s used to refer to any and all social responsibilities, broadly understood. But if we take the “citizenship” part of “corporate citizenship” seriously, then companies need to think seriously about what obligations they have as corporate citizens, which has to have something to do with their obligations vis-a-vis government. Regardless of how this mess all turns out, the charges currently being bandied about include things like “treason” and “espionage” and “threat to national security.” These are things that no good corporate citizen can take lightly.

Business Ethics and the “New York Times” Rule

On Monday, the front page of the New York Times featured at story about financial firms adjusting the timing of bonuses in response to anticipated changes in tax laws. I mention this story not because of the particular ethical issues involved, but because it was featured on the front page of The Times. How would you like your decision-making subject to that kind of scrutiny?

On Monday, the front page of the New York Times featured at story about financial firms adjusting the timing of bonuses in response to anticipated changes in tax laws. I mention this story not because of the particular ethical issues involved, but because it was featured on the front page of The Times. How would you like your decision-making subject to that kind of scrutiny?

From some perspectives, ethics is simple: “do the right thing.” For others (especially for philosophers like myself) it is incredibly complex, involving an ongoing centuries-old debate between arcane theories like deontology, utilitarianism, social contract theory, virtue theory, and others. In-between, we see lots of bits of ethical wisdom bundled into rules of thumb for ethical decision-making. Some of them are useful, some are misleading.

The one I’d like to discuss briefly today is the so-called “Front Page of the Newspaper” test, or sometimes “The New York Times Rule.” In one of its standard versions, it gets stated this way: “never do anything you wouldn’t want to see reported on the front page of the New York Times.” Some versions have additional qualifiers. Some, for example, say that you shouldn’t do anything you wouldn’t want to see fairly reported on the front page. That qualifier rules out slanted or malicious reporting — there are presumably plenty of fully-justifiable behaviours that we wouldn’t want to see reported in a malicious way, on the front page of the NYT or anywhere else.

The first thing to say about the Newspaper Test is that it probably is a useful heuristic. Asking the question it poses at very least serves as an opportunity to pause and ask yourself whether the action you’re about to take is one that could withstand publicity and scrutiny.

But there are two clear problems with the Newspaper Test.

One problem is that it can seem to serve as an argument against actions that are actually perfectly ethical. John Hooker, in his book Business Ethics as Rational Choice, gives this example: Imagine you’re CEO of a large corporation, and due to tough economic times you’re forced to lay off several thousand employees. Imagine that some of those employees slide into clinical depression. Others become alcoholics and end up beating their children. Lives are ruined. You probably wouldn’t want all of that reported on the front page of the NY Times, but that doesn’t mean your choice was unethical. In fact, Hooker points out, it might have been the least-bad option available. The point here is that sometimes even ethically good decisions are ones that we wouldn’t want publicized, either because their negative consequences are more visible than their positive ones, or because the reasons behind those decisions are reasons that, despite being good reasons, would be difficult or even impossible to explain.

The other problem is that it can seem to condone behaviour that is actually unethical. Most obviously, it can let you go ahead with an unethical plan if you happen either to be either generally insensitive to bad publicity or blind to subtle ethical dimensions of the question at hand. The former possibility is pretty self-explanatory: some people (and some companies) just don’t seem to care what the public thinks of them, or believe themselves to be above all need for accountability. As an example of the latter possibility (ethical blindness), picture a company sending its CEO to Washington on a private jet, with the aim of asking for money, and being utterly oblivious to the idea that the public might find this unseemly. If you don’t recognize, or care, that someone might object to your decision, then conducting the Newspaper Test isn’t going to stop you from doing something you shouldn’t.

The thing to remember about the Newspaper Test is that, like so many other catchy rules of thumb, it is at best a heuristic, and not an algorithm. It doesn’t automatically crank out an answer that is both determinate and correct. What it really is is an ‘intuition pump.’ It is a way to force yourself to ask, as part of a well-rounded ethical decision-making process, whether your decision is one that, in principle, you could defend in public. The hidden strength of the Newspaper Test lies in the notion of accountability, i.e., of having to give reasons for your actions in order to make them understandable to society at large.

Deadly Crashes, “Agency Theory” & the Challenges of Management

Sometimes for a corporation to “do the right thing” requires excellent execution of millions of tasks by thousands of employees. It thus requires not just good intentions, but good management skills, too.

Sometimes for a corporation to “do the right thing” requires excellent execution of millions of tasks by thousands of employees. It thus requires not just good intentions, but good management skills, too.

For an example, consider the story of the crash of a Concorde supersonic jet a decade ago. The conditions leading up to the crash were complex, but one factor (according to the court) was negligence on the part of an aircraft mechanic. Whether (or to what extent) that mechanic’s employer is responsible for that negligence, and hence at least partly responsible for the crash, is a difficult matter.

Here’s the story Saskya Vandoorne, for CNN: Continental Airlines and mechanic guilty in deadly Concorde crash

The fiery crash that brought down a Concorde supersonic jet in 2000, killing 113 people, was caused partially by the criminal negligence of Continental Airlines and a mechanic who works for the company, a French court ruled Monday.

Continental Airlines was fined 202,000 euros ($268,400) and ordered to pay 1 million euros to Air France, which operated the doomed flight.

Mechanic John Taylor received a fine of 2,000 euros ($2,656) and a 15-month suspended prison sentence for involuntary manslaughter….

I don’t know the details of this story well enough to have any sense of whether the mechanic in this case really did act negligently. But what intrigues me, here, is the issue of corporate culpability. Note the difficulty faced by airline executives who (for the sake of argument) want desperately to achieve 100% efficiency and never, ever to risk anyone’s life. In order to achieve those goals, executives have to organize and motivate hundreds or perhaps thousands of employees. They need to design and administer a chain of command and a set of working conditions (including a system of pay) that is as likely as possible to result in all those employees diligently doing their very best, all of the time. That challenge is the subject of an entire body of political & economic theory known as “agency theory.”

Agency theory and the various mechanisms available to motivate employees in the right direction are things that every well-trained business student knows about, because those are central challenges of managing any corporation, or even any small team. What is recognized too seldom, I think, is just how central a role agency problems play in assessing and responding to ethical challenges in particular.

Four Myths About Business Ethics

Here are four important myths about business ethics. There are surely many myths about business ethics, but these 4 in particular cause trouble, and pose significant challenges for anyone trying to have a productive discussion about right and wrong in the world of business.

Myth #1. “Business ethics” is an oxymoron.

The idea that “business ethics” is somehow a contradiction in terms is based on a serious misunderstanding of what ethics is and what the world of commerce is like. Indeed, it’s much closer to the truth to say that the term “business ethics” expresses a redundancy, since commerce is quite literally impossible without ethics. Every single commercial transaction requires some level of trust, and without a shared commitment to some level ethical behaviour, you simply do not get trust. Indeed, economists are more than ready to point out the huge range of ethical norms that underpin the modern economy and make it run more efficiently.

Myth #2. Ethics is just a matter of opinion.

Again, false. While ethics does of course have something to do with having an opinion, it’s also about having opinions that you can defend to other people. While there certainly are a few really tough moral questions about which we might agree to disagree, we should also recognize that on many ethical issues there are better and worse answers. Poor answers to ethical dilemmas are typically rooted in factual mistakes and logical inconsistencies. We shouldn’t settle for those. We should talk them through. (And, as a I blogged recently, having an opinion doesn’t come to much if you can’t sell that opinion to others.)

Myth #3. There’s no such thing as “business ethics,” because ethics should be the same everywhere.

There are two main reasons why ethics, while essential to business, isn’t just exactly the same in business as it is in other domains of life.

First, business poses special challenges. The enormous productive capacity of corporations and other large organizations also brings the potential to do substantial harm, both to the lives of stakeholders and to the natural environment. So we face questions in the world of commerce that we just don’t face in other parts of our lives. Second, the special social role of business implies a tailor-made set of ethical principles. One of the defining characteristics of business is that it is competitive: companies are naturally driven to do better than others in their field. This kind of behaviour is socially beneficial — consumers benefit when companies compete vigorously to produce a better product, at a better price, than the other guy. In practice, we can really look at business ethics as having two importantly different components. One component consists of the rules needed to civilize a tough, competitive game. This part of business ethics essentially has to do with the norms-and-principles that ought to govern business’s behaviour with regard to outsiders. The other component of business ethics is about the ethical rules that ought to be embodied in relationships within the organization. Here, we do value cooperative behaviour; so managers work hard to shape corporate culture to enable employees to trust each other and to work together toward shared goals. Business is morally complex that way.

Myth #4. Business ethics is just a matter of laws and regulation.

This is not just false, but dangerous. The tendency to confuse ethics and law is tempting, especially in an age in which the business section of the newspaper increasingly refers to “ethics laws” and “ethics regulations.” But we shouldn’t be misled by that short-hand way of speaking. If you think about it for just a minute or two, there are in fact lots of ways in which law and ethics come apart. There are plenty of things that are legal but unethical; and there are also behaviours that are illegal, but arguably ethically OK. The short explanation for the fact that law & ethics don’t overlap perfectly is this: laws are made & enforced by government. But governments can’t be everywhere, and if they could, we wouldn’t want them to be!

These surely aren’t all the myths there are about business ethics. But these strike me as four that are particularly common, particularly troublesome, and particularly clearly wrong.

Ethics as Strategy and Marketing

Ethical decision-making can helpfully be thought of as a matter of strategy and of marketing. This way of framing ethics is, I think, likely to be particularly useful in talking about ethics with either MBA students or business executives.

First it is worth noting that there is of course a cynical sense in which ethics can be a matter of strategy and marketing, and that’s when companies adopt an ethical posture because they see it as a good strategic move or as a smart marketing maneuver. That’s a good topic, but it’s not what I’m talking about here.

What I’m talking about is the sense in which very often, in the world of business, acting on one’s ethical convictions requires that one think in terms of strategy and marketing. An example may help.

Picture yourself working in a team-based work environment. Now imagine that the team decides to adopt a particular course of action, but it is one that you, after careful consideration, sincerely believe to be ethically problematic. OK, so you’re pretty sure you’re right.

Now what?

Well, knowing that you’re right doesn’t do much to change things, at least not automatically.

First comes a strategic decision. You need to choose a strategy, a course of action tailored to the situation. At the most basic level, your first strategic decision is whether to act or not. Maybe you’ll decide that discretion is the better part of valour, and end up holding your tongue. Maybe the issue is too small to be worth rocking the boat. But if the issue is worth pursuing, you’ll need to decide on a strategy for doing so. The thing that makes strategic decision-making difficult is the thing that differentiates strategic decisions from other sorts of decisions, which is that strategic decisions are decisions that need to take into consideration the decision-making of other people or institutions. (The contrast, technically, is with what are called “parametric” decisions, decisions that need only take into account facts about the non-decision-making bits of the world, such as “what is the weather like today?” or “how much money is in my pocket?”) So, in making a strategic decision about whether and how to voice concerns, you will need to think carefully about how other people are behaving, and how they will react to you — in other words, you need to think about what their strategies are likely to be, which is no trivial problem. That is the essence of strategic decision-making.

Next comes a marketing decision. (For practical purposes, the marketing decision might not be separable from the strategic one, but I’ll separate them for discussion purposes here.) Once you’ve decided that your strategy will indeed be to voice your concerns, how will you actually broach the topic? At a team meeting, or by means of quiet discussion with one or more key team members? If you need to seek like-minded allies, who will they be? And what will your sales pitch be? Will you cautiously express moral doubt, or will you pound your fist on a desk and declare the current course of action “unacceptable”? And just what will you be trying to sell the team — a small-but-meaningful shift in course, or a total about-face? The point is that you have not just to arrive at an opinion, but to sell it, too.

What we see here is that ethics is more complicated than simply knowing (or figuring out) the right thing to do.

But what I think we also see here is one more way to connect ethics with issues that managers and MBA students already take seriously. It’s a way of pointing out that ethics is far from the “soft” topic it is often accused of being. As someone with a Ph.D. in philosophy, I know that ethics is far from “soft” because I know a fair bit about the incredibly technical theoretical literature on the topic. But to many in the world of business, ethics is considered soft (while accounting, for example, is hard — firmly rooted in concrete realities). Pointing out that solving practical problems in ethics requires, among other things, solving challenging problems in strategy and marketing is yet another way to attempt rescue ethics from unfortunate perceptions of the topic.

What do “Higher Standards” for Business Look Like?

When we see what seems to be an increase in misbehaviour, we need to ask: is that because behaviour has gotten worse, or because expectations have gotten higher?

See this piece, by Theresa Tedesco, for Financial Post Magazine: Farther. Faster. Higher.

…Business leaders are on trial like never before. Public outrage over recent ethical crises and the dramatic failures of corporate governance, most notably the stunning collapse of Enron Corp. and the financial crisis of 2008, have fuelled assumptions that government and regulators are stepping in and that ethical standards of business must be on the rise as a result. Certainly, public awareness is heightened in the aftermath of spectacular corporate collapses. But are ethical standards actually getting higher as a result? Or are shareholders, employees and other stakeholders simply more aware of the moral considerations in the wake of these scandals and crises, considerations that are soon to be forgotten? Either way, the role of the modern CEO and other senior executives has become much more complex, driven almost reflexively by the velocity of change in social values, technology, regulation and, increasingly, public opinion….

(I’m also quoted, making a point I’ve made before, namely that business is more ethical today than it has ever been in the past.)

But there’s also an interesting philosophical question, here, about what counts as a “higher” standard.

In some cases, “higher standards” might actually mean that we attribute to business obligations in domains in which they previously were seen as having basically no obligations at all. Environmental concern might be one such domain. Once upon a time, pollution just wasn’t an issue. At even once pollution was “on the radar,” so to speak, specific types of pollution (e.g., CFC’s) still weren’t seen as important. In that sense, it’s clearly true that we see “higher standards” imposed, and observed, by business today.

A second kind of “higher standards” might involve stricter requirements for things like honesty and product safety and truth in advertising. Once upon a time, the rule really was “buyer beware.” That’s no longer the case. Social expectations, often backed by law, mean that businesses face (and generally adhere to) standards far higher than we’ve ever seen before in history.

A third kind of “higher standard” might have to do with social expectations with regard to the impact business has beyond its interactions with its own customers and employees. Now, it has long been the case that many businesses make social contributions through things like charitable donations. But today, it is utterly run-of-the-mill for companies to have CSR departments that consider not just things like charitable donations, but how to track and report on the business’s net social impact. This is yet another way in which businesses face, and face up to, higher expectations.

But there is also a fourth kind of higher standard, one which is less-obviously being met. And that is in the area of individual decision-making. When the average person (or the ethicist, for that matter) surveys the world of business, he or she still sees examples of bad behaviour — people lying, cheating, embezzling, and defrauding. Most of us get our data in that regard from the media, which is far from a fair accounting of the issue. But still, the cases are out there. And it’s in that sense that people are very fair to observe that, at very least, things don’t seem to be getting better, dammit. Then again, I know of no credible evidence that things are getting any worse in this regard.

I suspect different people mean different things when they talk about whether “ethical standards” are higher or lower in business today. I suspect that the first 3 kinds of “higher standards” above are the crucial ones, since I suspect that the 4th, which depends on the character of individual human beings, is less susceptible to long-term change on a population basis.

Comments (13)

Comments (13)