Is 7-Eleven My “Neighbour”?

I live on the edge of Toronto’s Little Portugal. There are two corner stores in my neighbourhood. One is a 7-Eleven. The other is a small, family-owned convenience store. I shop at both stores from time to time — to pick up eggs, bread, whatever.

Is there any ethical difference between shopping at 7-Eleven, on one hand, and shopping at the little Portuguese place, on the other?

At least some advocates of the “buy local” movement would say I absolutely ought to shop at the locally-owned Portuguese place. After all, it’s a part of my community, whereas 7-Eleven is a multinational corporate entity. But wait…7-Eleven is a franchise. So even though the parent company isn’t local, the owners of the franchise very likely are. The owners of that franchise are just as much part of my community as the owners of the Portuguese place are…minus the franchise fee they pay to Seven-Eleven Japan Co. Ltd. (Does that count?)

But still, the 7-Eleven, even if locally-owned, is still part of the 7-Eleven empire. When I shop at my 7-Eleven, I’m patronizing that empire. I am, to some extent, entering into a relationship with the parent company. So this question occurs to me: is Seven-Eleven Japan Co. Ltd. in any sense my “neighbour”, one to which (or to whom!) I owe the neighbourly obligation of shopping at their franchise?

Major corporations are increasingly expected to think of themselves as good neighbours, and as having obligations to local communities. But the “neighbour” relation is generally thought of as being reciprocal, as are the duties it implies. If you are my neighbour, then I am your neighbour, and vice versa. So if 7-Eleven, and other major corporations, are expected to act as good a neighbour, should we all reciprocate, and act as good neighbours to them in turn?

I don’t have an answer to offer to this question. But I think the reciprocity that is normally a feature of the concept “neighbour” ought to be part of the larger conversation about how we think of the role of business corporations not just in our economy, but in our communities.

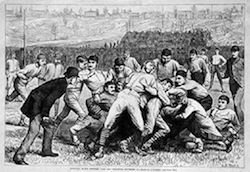

Football and Commerce: The Importance of the Rules of the Game

It’s often pointed out that business is a tough, hard-hitting game. In fact, that’s often cited as a reason for skepticism about any role for ethics in business. After all, ethics is (so they say) about good behaviour, not about aggressive competition. And there’s just no role for nicey-nicey rules in the rough-and-tumble world of business.

It’s often pointed out that business is a tough, hard-hitting game. In fact, that’s often cited as a reason for skepticism about any role for ethics in business. After all, ethics is (so they say) about good behaviour, not about aggressive competition. And there’s just no role for nicey-nicey rules in the rough-and-tumble world of business.

But, of course, nothing could be further from the truth. Rules are endemic to commerce, as they are to all other competitive games played by people in civilized societies. The rules of the game, after all, and the fact that most people play by them most of the time, are what differentiate commerce from crime.

This point is nicely illustrated by the serious scandal in which Football’s New Orleans Saints are currently embroiled.

The facts of this scandal are roughly as follows: players on the team, along with one assistant coach, maintained a ‘bounty pool’ amounting to tens of thousands of dollars, from which bounties were paid to players who inflicted serious injuries on players from opposing teams. This violates the NFL’s “bounty rule,” which specifically forbids teams from paying players for specific achievements within the game, including things like hurting other players. Why would the League have such a rule? Don’t they understand that football is a tough, hard-hitting game?

A game like football in fact has a couple of different kinds of rules. One kind of rule is there merely to define what the game is. The rule in football that says you can only throw the ball forward once per down is such a rule. The rule could easily be different, but the rule is what it is, and it’s part of what constitutes the game of (American) football. Other rules — including those that put limits on violence, and those that prescribe the limits on the field of play — have a more crucial role, namely that of ensuring that the game continues to be worth playing. Football (and hockey and a few other sports) involve controlled aggression and controlled violence, of a kind that would be considered seriously problematic, even illegal, if it took place outside of a sporting event.

The reason we consider such ritualized violence acceptable is that it is conducted according to a set of rules to which all involved consent. Players recognize that they might get injured, but they presumably feel it worth the chance of being injured in return for some combination of fame, glory, and a sizeable income. In addition, there are significant social benefits, including especially the enjoyment of fans who are willing, in the aggregate, to spend millions of dollars to patronize such sports. So the deal is basically that we, as a society, allow aggressive, violent behaviour, as long as it is played by a set of rules that ensures that a) participation in the game is mutually-beneficial and b) no one on the sidelines gets hurt.

The New Orleans Saints’ bounty system violated that social contract. It undermined the very moral foundation of the game.

And that is precisely how we ought to think of the rules of business. Yes, it’s a tough, adversarial domain. Apple should try to crush Dell by offering better products and better customer service. Ford must try its best to outdo GM, not least because consumers benefit from that competitive zeal. Indeed, failure to compete must be regarded as a grave offence. But competition has limits. And the limits on competitive behaviour are not arbitrary; nor are they the same limits as we place on aggressive behaviour at home or in the street.

The limits on competitive behaviour in business, however poorly-defined, must be precisely those limits that keep the ‘game’ socially beneficial. And it’s far too easy to forget that reasonably-free capitalist markets are subject to that basic moral justification. When done properly, such markets offer remarkable freedom and unparalleled improvements in human well-being. Behaviour that threatens the tendency of markets to produce mutual benefit effectively pulls the rug out from under the entire enterprise. Such behaviour is an offence not just to those who are hurt directly, but to all who enjoy — or who ought to enjoy — the benefits that flow from such a beautiful game.

Social Class and Unethical Behaviour

Hating the rich comes pretty naturally to a lot of people. And so it’s not surprising that a widely-reported study apparently demonstrating that the rich are less ethical resulted in a combination of glee and eye-rolling proclamations that “we already knew that.”

Hating the rich comes pretty naturally to a lot of people. And so it’s not surprising that a widely-reported study apparently demonstrating that the rich are less ethical resulted in a combination of glee and eye-rolling proclamations that “we already knew that.”

There’s plenty to say about the study — lots of people (mostly in the comments accompanying various reports on the study) have pointed to what they say are methodological weaknesses related to sample size, how participants were chosen, what kinds of tests are taken as proxies for a lack of ethics, etc.

But if we take as given the conclusion that the rich do behave less ethically (by certain measures) this raises the question of what causes such behaviour on the part of the rich. To their credit, the study’s authors at least gesture at subtlety: “This finding is likely to be a multiply determined effect involving both structural and psychological factors.” But the authors do spend an awful lot of time discussing what they clearly take to be the key causal factor, namely greed. “Greed,” the authors write, “is a robust determinant of unethical behaviour.”

But the role that greed plays is in fact very far from obvious. The citations given by the authors are not entirely compelling, and as I’ve pointed out before, there’s considerable evidence (found primarily in the literature on criminology) that greed is not a key explanatory factor in much wrongdoing. Wrongdoing is more generally explained by the capacity for rationalization, for telling oneself compelling stories about why one’s own behaviour isn’t wrong after all.

It’s also worth pointing out the more general problem with establishing causal relationships. Note that the title of the study says only that “Higher social class predicts increased unethical behaviour” [emphasis added]. But the headline writers for various news outlets are not so careful: Wired, for example, tells us that “Wealth Could Make People Unethical” [emphasis added]. And the distinction is important. Owning an ashtray may predict increased tendency toward lung cancer, but we’re pretty sure that ashtrays don’t cause lung cancer. So is being rich making people unethical, or is being unethical a route to getting rich, or are both the result of some third factor, like ambition?

What’s the practical upshot of all this? That, too, depends on the direction of causation. If being rich makes less ethical, then you have a reason — perhaps not a compelling one — to worry about the effect that your own increasing wealth might have on your morals. And, given what I said above about the role of rationalization, you ought to watch yourself for signs that you’re telling yourself those comforting little stories that make you feel better about behaviour that you know, deep down, is unethical.

If, on the other hand, being less ethical is a route to riches — well, that points in a couple of different directions. For individuals, the dangerous and cynical conclusion is that you need to learn to bend the rules to get ahead. But from a systems point of view, the implication is quite different: how do we design institutions so that ethical, socially-constructive behaviour is rewarded, and that socially-destructive but individually-profitable behaviour is not?

The third possibility — that some third factor, like ambition is the crucial causal factor — has implications also. This possibility raises the question of social tradeoffs. What if a certain amount of anti-social behaviour is the quid pro quo of entrepreneurship and creativity? Is the amount of social good done by ambitious people sufficient to make us tolerate a certain amount of unethical behaviour? History is full of accounts of crummy human beings with the vaulting ambition to produce great works of art, literature, and science. Steve Jobs was, by all accounts, a difficult guy to say the least, and had a habit of treating people very, very badly throughout his career. But then, he also gave the world a lot of ‘insanely great,’ innovative products.

Of course, whether such trade-offs are worthwhile is a world-class philosophical problem, the answer to which is far from clear. But what’s much more clear is that individuals can’t rightly help themselves to the relevant justifications. We can’t excuse our own bad behaviour by pointing to our productivity. We are all far, far too likely to overestimate our own social contributions, and to underestimate our own foibles and peccadilloes. And that, it seems to me, is the root of a much more likely explanation of patterns of unethical behaviour than is the simplistic assumption — an assumption that all too often simply reaffirms a cynical worldview — that it all really boils down to greed.

Individual Discretion and Institutional Design

I’m just back from the University of Redlands, just outside of Los Angeles, where I spoke at the wonderful Banta Center for Business, Ethics and Society. The topic of my talk there was “Responsibilities in the Blogosphere,” but the key themes of that talk apply pretty directly to the world of business more generally.

I’m just back from the University of Redlands, just outside of Los Angeles, where I spoke at the wonderful Banta Center for Business, Ethics and Society. The topic of my talk there was “Responsibilities in the Blogosphere,” but the key themes of that talk apply pretty directly to the world of business more generally.

One of the key themes had to do with the tension between a focus on individual decision-making on one hand and a focus on institutional design on the other, between a focus on individual responsibilities and a focus on how Internet giants like Google and Facebook construct online worlds that shape our behaviour.

There’s an awful lot of focus — too much, in my opinion — on individual decision making in ethics. In fact, a focus on individual decision-making is kind of the default, both in philosophical ethics and in more applied areas. The key questions, for many people, are general questions like “How should I behave?” “How should I resolve an ethical dilemma?” and “What factors should I take into consideration in ethical decision-making?”

And to be sure, that kind of focus makes for some great after-dinner speeches. The focus on the individual is empowering: “it all comes down to you.” “Your choices matter.” “We can do better, if each of us just changes how we think.” “It’s all about integrity.” And so on. More than that, individual ethical dilemmas really do have a huge impact on individuals, and so it behooves those of us in the ethics biz to do something to offer some guidance. (One modest contribution of mine to this area is my Guide to Moral Decision Making.)

But there’s a real sense in which the focus on the individual is a distraction. Individuals will make the decisions they make, and those decisions will in large part be determined by forces that are a) psychological and cultural, and b) institutional.

So the real focus should be on institutional design, on devising institutions to foster the right kinds of behaviours. And I’m talking about institutions in the broadest sense, which includes not just corporate frameworks and governance structures, but also traditions and norms and social conventions.

Greater attention to institutional design is more than just a remedy to the excessive (and perhaps futile) attention paid to individual decision-making. It changes the way we frame discussion of ethics in that it makes it clear that business ethics isn’t just a microcosm of everyday ethics. It is instead a matter of using human ingenuity to build ways of doing things that suit the situation at hand: devising rules and norms that put reasonable constraints on human behaviour, to make sure that business stays mutually advantageous. But we’re not building entirely from scratch: rules and other normative institutions in the world of business still have to be ones that can be understood and applied by the human beings who inhabit that world. The software, in other words, has to match the hardware.

Don’t get me wrong. I’m not against thinking about individual decision-making. I teach a course on critical thinking, and I think all of us can learn to think more critically about ethical issues in business, to avoid certain well-known fallacious arguments, and so on. But the emphasis on design helps makes clear that ethics in business is a realm for innovation, and isn’t just a matter of importing into the world of commerce the values you learned at your mother’s knee.

——–

Note: Some of the thinking here was inspired by a conversation with my friend & former student, Garrett Mac Sweeney).

Business Ethics & Pride in a Job Well Done

One of my shoe laces gave out today, on the way out the door heading to the airport. Luckily the shoe-shine guy, in addition to giving an excellent shine at a good price, also had reasonably-priced laces which he happily threaded and tied for me.

One of my shoe laces gave out today, on the way out the door heading to the airport. Luckily the shoe-shine guy, in addition to giving an excellent shine at a good price, also had reasonably-priced laces which he happily threaded and tied for me.

For some strange reason, it always comes as a shock to me when a shoe lace gives out. The odd thing is that I usually cannot remember how old the disappointing lace actually is. I honestly cannot tell you whether the lace that gave out today is 3 months old or a year old or three years old. Nor do I know what brand it was, or where I bought it. So — setting aside, for a moment, its trivial price — I have no idea who I would complain to if I thought the lace had given out sooner than it ought to have.

Given this lack of accountability, one has to wonder just what it is that motivates makers of shoe laces (or other small, cheap, anonymous products) to rise above the bare minimum in terms of quality. Shoe laces are not, presumably, a highly-regulated industry. So they could presumably get away with using cheap raw materials, keeping costs down and profits high.

One obvious answer is “ethics.” The people who make shoe laces presumably have some pride in their work, and want people to be satisfied with their laces, and feel that it’s their responsibility to produce a decent product.

Another answer might have something to do with supply chains. Maybe I can’t easily hold the maker of my laces accountable, but the store I bought them at can. Maybe the purchasing agents for the store I bought them at asks lots of tough questions and demands access to technical specifications for laces before buying. I hope that’s the case. But that just pushes the question one link higher up the supply chain. Why does the purchasing agent care, given how likely consumers are to express their disappointment, in the event that they are dissatisfied? Again, the likely answer here is “ethics,” a big part of which is the simple motivation to do a good job and treat people fairly.

OK, so this is a trivial little example. But it seems to me that it points to an important lesson. People too often think of the word “business ethics” as implying an attempt to define and achieve saintly behaviour in business. And that’s a mistake. What we’re really talking about are reasonable constraints, and reasonable standards of achievement, in the world of commerce. We’re all out there, trying to make a living, and there are better and worse ways to do that. And whether you’re manufacturing shoe laces or complex financial instruments, the starting point has to be basic pride in a job well, and fairly, done.

Ethical Complexity and Simplification in Food Choices

As I pointed out a few days ago, shopping ethically is hard. Right on cue, a flurry of news items followed to drive that point home.

First, a story about how — say it ain’t so! — local food isn’t always ethical food. The story points out that some agricultural workers in southern Ontario (just a short drive from where I live) report suffering from a range of ailments that they attribute to the chemicals to which they are exposed. So, yes, there’s more than a single dimension to food ethics. If (or rather when) local is actually better, that’s got to be an “other things being equal” sort of judgment. Local might be better — so long as local farm workers aren’t being abused, and so long as growing food in your local climate doesn’t require massive water and fuel subsidies, etc.

Next, a Valentine’s-themed bit on how to buy ethical chocolate. The short version: apparently you’re supposed to look for local, organic chocolate that’s certified free of child-labour, sold in a shop that dutifully recycles and composts. Of course, such chocolate isn’t necessarily cheap. And if you’re spending that much on chocolate, then you might want to think what other things you’re scrimping on as a result, and who might be affected by that scrimping.

Finally, there was a story — really just a press release — noting that chocolate bar manufacturer Mars is set to ‘help’ consumers by narrowing their choices: the company is aiming to put a 250-calorie limit on all its bars by 2013. Interesting question: is this a matter of helping particular customers, by encouraging them not to over-indulge? Or is it rather a matter of specifically social responsibility, an attempt by a food giant to respond to (or at least to limit its contribution to) the social problem of obesity? And — speaking of value choices — should food companies aim first and foremost at pleasing their customers, or serving society as a whole?

Ethical Consumerism is Hard

It’s not easy being an ethical consumer, these days — especially if you’re hoping to buy products that embody all or most of the ethical values you care about.

It’s not easy being an ethical consumer, these days — especially if you’re hoping to buy products that embody all or most of the ethical values you care about.

Here’s an example. If you like salmon, and if you’re the sort of consumer who wants to eat ethically, should you buy organic salmon or buy wild salmon? After all, there’s a huge effort these days to promote organic foods as ethical — gentler on the earth, and so on. Of course, others aren’t so sure that there’s much benefit to organic foods, and some even argue that the organic label is more a status symbol than anything else.

Now what about wild vs farmed? Some people think that farmed salmon is always bad. Others, like food-policy expert James McWilliams, argue that for whatever its current flaws, farmed fish provides our best hope for a future that includes significant amounts of protein at acceptable environmental costs. Eating wild fish, on the other hand, puts pressure on fragile wild populations.

But still, there are plenty of people who are dedicated to eating organic, and plenty of people who are quite insistant upon eating only wild fish.

The problem is, you can’t have it both ways. Wild salmon cannot, by definition, be organic, because it’s impossible to control what wild salmon eats. It can only be truly organic if it’s raised in captivity. Damned if you do, damned if you don’t.

This is just one tiny example of the challenges of ethical consumerism. Any given product can embody any number of incommensurable values — values that can’t just be added up to arrive at a total “ethics quotient.” The same problem applies to wind power (which produces no air pollution but kills birds) and oil from Canada’s oil sands. (which is produced in a democracy but is environmentally-dodgy).

Of course, none of that means that it’s not worth some effort to try to buy conscientiously. It just means that, as often as not, values-based consumerism is going to mean purchasing according to values that matter to you, rather than hoping to buy in a way that is ‘truly ethical,’ in some grander sense.

If Facebook Were a Country, Would Zuckerberg Be King?

I’m serious. Is Mark Zuckerberg aiming to be the hereditary sovereign of the Kingdom of Facebook?

Amid all the ballyhoo about the Facebook IPO, concerns have arisen about the ownership structure — and, hence, governance structure — structure that the company’s plan implies. As Matt Yglesias recently outlined, the current plan implies considerable continuing power for Zuckerberg. Given the number of Class B shares he owns, along with proxies he controls, Zuckerberg effectively has “57 percent of the voting rights over the company.” In addition, his control will be transferred to whomever inherits his fortune.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing? A couple of points, both having to do with how Zuckerberg will use his power.

One is that, interestingly, Zuckerberg has (in a letter to investors) disavowed a focus on profits:

“Simply put: we don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services.

And we think this is a good way to build something. These days I think more and more people want to use services from companies that believe in something beyond simply maximizing profits….”

Some will rejoice at this. But of course, when a company says it’s going to aim at things beyond profits, there’s no particular reason to think that they’ll aim instead at goals you approve of. Facebook is a powerful company, grounded on a potent technology. Whomever controls it has the power to do a lot of good, or a lot of evil. And as I’ve pointed out before, Zuckerberg holds some dangerous views about, for instance, things like privacy.

Some of the comments under Yglesias’s piece have suggested that Yglesias exaggerates just how unique Facebook is in this regard. Other companies have been controlled by powerful central figures. Fair enough, but Facebook isn’t your average company. In a very real way, Facebook is becoming part of the infrastructure of modern life. In its role, it is more like a public utility than a private company. That puts the company — and its leader — in a very different position than, say, Ford or Exxon. Facebook really is more like a nation, and so he who controls it really is more like a political leader. This casts a very different light on how we evaluate not just the man, but the processes that are in place to guide his judgment.

Child Labour in North America

Once upon a time, I was a child labourer in the agricultural sector.

Once upon a time, I was a child labourer in the agricultural sector.

You see, I grew up on a small farm. I learned to drive a tractor when I was 10 years old. I was barely strong enough to push the clutch pedal all the way in. By 12, I was loading bales of hay onto wagons and feeding livestock. Like thousands of other youngsters across North America, I was part of a middle-class farm family.

Of course, my experience — and, I would think, the experience of other farm kids in North America — was worlds apart from the brutality of child labour in developing nations. But there is at least some overlap in terms of ethical issues.

So I’ve been interested to see the debate over proposed changes to US labour laws. The proposed changes “would ban children younger than 16 from using most power-driven equipment and prevent those younger than 18 from working in feed lots, grain bins and stockyards….” The only exception would be children working on farms “wholly owned” by their families.

I don’t have a strong point of view to put forward on this issue. I know I learned a lot as a farm kid, and my parents always made sure I was safe. But growing up on a farm, even a North American farm, isn’t always a positive experience.

All I want to point out here is that there are a couple of importantly-different levels to this controversy.

One level has to do with the conflict between parental autonomy and government regulations designed to protect children. Kids are among society’s most vulnerable members, and some parents are careless, and so government has some obligation to promote their safety and wellbeing. But on the other hand, a society in which parents were not allowed to make important lifestyle decisions for their children — including some risky ones — would be intolerable. (Note: far more children die of drowning each year than die in agricultural mishaps. Never mind automobile accidents.)

But the other level here has to do with regulation and the complexity of human business activities.

You see, the details of the above story, about revising US labor laws, illustrate the difficulty inherent in writing regulations. When US labour laws were originally devised, the meaning of the term “family farm” may have been relatively clear and succinct. So it made sense to say that kids, while generally forbidden from working, could still work on their parents’ “family farm.” But as the story points out, the current proposal “did not consider the thousands of farms nationwide that are owned by closely held corporations or partnerships of family members and other relatives.” In other words, there’s more than one way to structure a business that fits the basic criteria for what we would legitimately call a “family farm,” of the kind that merits a (partial) exemption from child labour laws.

And so this case provides just one more little example of the general principle that regulations aimed at regulating business face the eternal challenge of keeping up with varying and evolving business practices. That means not just headaches for regulators, but also heightened obligations for business to self-regulate.

Sustainability Isn’t Everything

The word “sustainability” doesn’t just refer to everything good. If it did, we wouldn’t need the word “sustainability” at all; we would just use the word “good.”

I’m just a small-town philosopher who likes words to mean what they mean. That’s why I got cranky when I saw the new Global 100 Ranking, which is ostensibly a sustainability ranking. (See my blog posting here.) Why cranky? Because over half of the criteria used to arrive at that ranking have nothing to do with what I — and, I suspect, most people — think of when they hear the word “sustainability.”

But let’s set aside the fact that this usage is potentially misleading; words evolve, and maybe the public will catch up with the Global 100 in its broad understanding of the term “sustainability.” Does this new, revised meaning of “sustainability” make sense?

Let’s start with the word “sustainable.” Well, standard dictionary definitions suggest that it means something like, “Able to be maintained at a certain rate or level.” OK, good. That’s a positive thing, right? But wait. No one cares about corporate sustainability in that sense, with the possible exception of certain narrow-minded shareholders. We want businesses that are more than merely capable of being maintained. We want businesses that are worthy of being maintained.

So sustainability needs some normative content. It needs some goodness baked in.

In this regard, the touchstone is the U.N.’s Brundtland Commission. In 1987, the Brundtland Commission asserted that “sustainable development is development that meets the needs of the present without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own needs.” And ever since then, at very least, the words “sustainable” and “sustainability” have had very significant environmental overtones. OK, good. Here, “sustainability” is being used to indicate some plainly good things: environmental sustainability isn’t the only good thing in the world, but it’s definitely a good thing from a social point of view, embodying not just the value of the natural environment but also a sense of intergenerational justice.

But some people (including the people behind the Global 100) want to expand the term “sustainability” to include other, non-environmental dimensions. From a certain point of view, this makes sense: other things required to allow a company to “sustain” operations. But then further problems arise.

Note that when we expand “sustainability” this way, a subtle bit of sleight-of-hand takes place. Previously, we were talking about business operations that were environmentally sustainable. Now, we’ve switched to sustainable organizations. What does it take to sustain an organization? Lots of things, and not all of them are good. And being sustainable isn’t, in itself, a good thing. The tobacco industry has lasted for centuries, leaving millions of dead bodies in its wake. Very, very sustainable. But bad.

As noted above, we don’t generally care whether companies can stay in business. We want them to merit staying in business. And if the companies on the Global 100 merit staying in business, why not just say so?

In the end, I guess my point really is that environmental sustainability is important all on its own, and doesn’t need to be fluffed up with issues like workplace safety or leadership diversity or CEO pay; and issues like workplace safety and leadership diversity and CEO pay are too important to stuff into the simple concept of sustainability.

Comments (1)

Comments (1)