Archive for the ‘accountability’ Category

The Hidden Ethical Value of Social Networking

Like it or not, we are in the middle of a social networking revolution. And of course, that’s hardly news. Endless ink, digital and otherwise, has been spent on worrying over whether Facebook, Twitter, and their rapidly-multiplying ilk are the best or the worst thing that has ever happened to humankind.

Like it or not, we are in the middle of a social networking revolution. And of course, that’s hardly news. Endless ink, digital and otherwise, has been spent on worrying over whether Facebook, Twitter, and their rapidly-multiplying ilk are the best or the worst thing that has ever happened to humankind.

A recent story about car-pooling apps highlights the fact modern technology, including social media, has a role to play in making markets more efficient. And since efficient markets are generally a good thing, this counts as a big checkmark in the “plus” column of our calculations concerning the net benefit of social media.

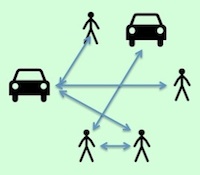

Carpooling is a great example, because the relative lack of carpooling today is a clear instance of what economists call “market failure” — a situation in which markets fail efficiently to provide a mutually-beneficial outcome. Think of it this way. There are lots of people in need of a ride. And there are lots of people with rides to offer. The problem is a lack of information (who is going my way, at what time?) and lack of trust (is that guy a potential serial killer?) Social networking promises to resolve both of those problems, first by helping people coordinate and second by using various mechanisms to make sure that everyone participating is more or less trustworthy.

With regard to car-pooling, the obvious benefits are environmental. But the positive effect here is quite general: just about any time we find a way to foster mutually-advantageous market exchanges, we’ve done something unambiguously good. This is one example of the ethical power of social media.

Another big enemy of efficient markets is monopoly power, or more generally any situation in which a buyer or seller is able to exert “market power,” essentially a situation in which some market actor enjoys a relative lack of competition and hence has the ability to throw its weight around. Social media promises improvements here, too. Sites like Groupon.com allow individuals to aggregate in ways that give them substantial bargaining power.

The general lesson here is that markets thrive on information. Indeed, economists’ formal models for efficient markets assume that all participants have full knowledge — that is, they assume that lack of information will never be an issue. Social networks are providing increasingly sophisticated mechanisms for aggregating, sharing, and filtering information, including important information about what consumers want, about what companies have to offer, and so on. So while a lot of attention has been paid to the sense in which social media are “bringing us together,” the real payoff may lie in the way social media render markets more efficient.

Executive Compensation at a Regulated Monopoly

Protests broke out last week at the first annual shareholders’ meeting of Canadian energy company, Emera. Emera is a private company, traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. But one of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, Nova Scotia Power, is the regulated company that supplies Nova Scotia with virtually all of its electricity.

The protest concerned the fact that several Emera and Nova Scotia Power executives had received substantial raises, despite the fact that Nova Scotia Power had just recently had to go to the province’s Utility and Review Board to get approval to raise the price it charges Nova Scotians for electricity. According to the utility, the rate hike was needed to add new renewable energy capacity to Nova Scotia’s grid. But protestors wondered if the extra cash wasn’t going straight into the pockets of wealthy executives.

The first thing worth pointing out for anyone not already aware is that practically no one thinks that anyone is doing executive compensation particularly well. Sure, most boards have Compensation Committees now, and many big companies engage compensation consultants to do the relevant benchmarking and to make recommendations. But no one is particularly confident in either the process or the results. So Emera’s board is far from alone in facing this kind of critique.

The second point worth making is that there are two very different kinds of stakeholders concerned in a case like this, but in this particular case they happen to overlap substantially. On one hand, there are Emera’s shareholders. They have an interest in making sure the company’s Comp Committee does its job, and sets executive compensation in a way that attracts, retains, and motivates top talent in order to produce good results. On the other hand, there are customers of Nova Scotia Power, ratepayers who want a cheap, stable supply of electricity. Now, as it happens, many of the vocal protestors at Emera’s annual meeting are members of both groups: they are shareholders in Emera and customers of Nova Scotia Power. But it is crucial to see that these are two separate groups, with very different sets of concerns. When this story is portrayed as a story about angry shareholders, this crucial distinction gets blurred. What’s good for shareholders per se is obviously not the same as what is good for paying customers. And, importantly, a company’s board of directors aren’t accountable to customers in the same way that they are to shareholders.

The final point to make about this is that, to observers of corporate governance, this is actually a “good news” story. As noted above, no one thinks executive compensation is handled very well. But despite that fact, corporate boards still face relatively little pushback from shareholders, and are relatively seldom held to account in this regard. There are of course exceptions (including a number of failed “say on pay” votes) but those exceptions prove the rule. And that’s unfortunate. In any ostensibly democratic system, it is a good thing when the voters take the time to show up and to ask hard questions. Even if no one is sure that such participation improves outcomes, it is an invaluable part of the process.

———-

(I was on CBC Radio’s Maritime Noon show to talk about this controversy. The interview is here.)

———-

Did Apple’s CEO Forego $75 million as a Matter of Principle?

There’s tone at the top, and then there’s tone at the top of the top. And when it comes to defining “top,” it’s hard to beat being the highest-paid CEO in the world, leading the most valuable company in the world. The man who occupies that post, of course, is Apple Inc.’s Tim Cook.

And recently, Cook made a pretty big move that might well do something to set the tone among high-end CEO’s. According to SEC filings, Cook reportedly has opted to take a pass on dividends he could have collected on over a million unvested shares. In total, that amounts to passing up about $75 million. Not that this is exactly going to leave Cook in the poorhouse — he’s paid a mind-boggling amount of money for the task of trying to fill Steve Jobs’s shoes. But still, it’s not trivial either. What should we make of it?

There are a couple of ways to think about this.

One has to do with shareholder confidence. Some have suggested that the decision is designed to show that Apple’s recent decision to pay a dividend wasn’t intended to benefit Cook himself. It is good for the investing public to know that the company is making decisions about things like dividends with the the best interest of shareholders in mind, rather than the best interests of the CEO. But then, Apple isn’t exactly suffering a crisis of shareholder confidence. If boosting the image of the company’s leadership is what you’re looking for, this might just be overkill.

But there’s another way to think of this, and that has to do with the good old-fashioned notion of honour. Call me a hopeless romantic, but I like to think that Cook’s decision might have something to do, as an unnamed source told the Telegraph, with setting an example for his fellow CEOs. Executive compensation has been in the spotlight almost continually for the last couple of years, and has even been the focal point of shareholder revolts. Maybe this is Cook’s way of saying, look, a high-end CEO doesn’t always have to squeeze every penny he can out of the company. And it’s entirely plausible, I think, that someone like Cook might make that decision — and send that signal — as a matter of principle.

“Honour” is the right moral category, here, because foregoing the cash is not something Cook is ethically obligated to do. He is fully within his rights, both legally and ethically, to take the dividend like other shareholders. But there’s arguably something good, something admirable, about attempting to shift the tone among high-end CEOs this way. It’s one thing to say that CEOs are overpaid. It’s quite another to set an example.

Will Cook’s move have any impact? Who knows. But it does seem like one more interesting attempt by the folks in Cupertino to get someone to “Think Different.”

Should JPMorgan Fire the London Whale?

Would you fire an employee responsible for losing your company a couple billion dollars? I mean, hey, mistakes happen. But we’re talking two billion, here, with a “B”.

It’s not a hypothetical question, at least not for one major financial institution. As has been widely reported, JP Morgan Chase has now acknowledged that recent trading losses of two billion dollars are “somewhat related” to the controversial activities of a single London-based broker. The broker, whose real name is Bruno Iksil but who is often referred to as The London Whale, made enormous bets on U.S. corporate bonds…and lost.

I don’t think anyone has seriously suggested firing The Whale, at least not in public. But it does make you wonder. Even a company the size of JPMorgan can’t quite shrug off losses of that magnitude. And as others have pointed out, the hit to the company’s reputation may be more damaging, in the long run, than the short-run hit to its bottom line.

It’s worth noting that The London Whale was not a rogue trader. Indeed, his strategy was widely known, and apparently approved of by top executives at the company’s chief investment office.

Still, executive approval or no, it would be easy enough to make a scapegoat of The London Whale. But of course, that would be disingenuous, and the complicity of the Whale’s bosses is now public knowledge. And anyway, it’s entirely possible that the company will continue to see him as a valuable trader. He lost money this time around, but only insiders have the numbers to know how much he has made or lost for the company during his years there. And it’s entirely possible for even a losing bet to be regarded as one that it was smart to make in the first place.

There is also a public interest angle here. One of the key lessons of the last 4 years has been that innovative risk-taking by financial institutions can be a threat to the public good, not to mention the public purse. So even if The London Whale, and his overseers, aren’t destined to be axed by those who serve the company’s shareholders, that doesn’t mean they don’t collectively deserve our opprobrium, in addition to warranting stricter regulation.

The Problems With the “People’s Rights Amendment”

Corporate personhood is one of the most badly misunderstood concepts in discussions of corporate behaviour and responsibility. It is also one of the most essential tools for promoting human wellbeing and protecting individual human liberties.

People get angry — understandably and often justifiably angry — when they see instances in which corporations have too much power. But the response, the way such anger is directed, is not always constructive. Indeed, sometimes it’s downright counterproductive.

Witness, for example, the recent move in the US to propose a “People’s Rights Amendment.” (It’s a project of citizens group “Free Speech for People”, and the bill was introduced in congress by Congressman Jim McGovern of Massachusetts.) This is a hail-Mary attempt to amend the US Constitution, largely in response to the US Supreme Courth’s controversial Citizens United decision. That decision, rooted in constitutional arguments about free speech, removed certain limits on corporate political donations. Like many people, I worry about the effects of that decision; but I worry even more about the potentially disastrous effects of the proposed remedies.

Now, a lot of people believe that the US Supreme Court, in the Citizens United decision, invented the notion of Corporate Personhood. That belief is both false and wildly US-centric. But aside from getting history wrong, this belief has resulted in a backlash that has included some wrong-headed proposals for shifting the balance of power back to The People. And the People’s Rights Amendment is one of those.

Here are the 3 sections of the proposed “People’s Rights Amendment”:

Section 1. We the people who ordain and establish this Constitution intend the rights protected by this Constitution to be the rights of natural persons.

Section 2. People, person, or persons as used in this Constitution does not include corporations, limited liability companies or other corporate entities established by the laws of any state, the United States, or any foreign state, and such corporate entities are subject to such regulation as the people, through their elected state and federal representatives, deem reasonable and are otherwise consistent with the powers of Congress and the States under this Constitution.

Section 3. Nothing contained herein shall be construed to limit the people’s rights of freedom of speech, freedom of the press, free exercise of religion, and such other rights of the people, which rights are inalienable.

There are two problems here, and they are rooted in Sections 2 and 3 respectively.

Note that Section 2 says that incorporated entities don’t get constitutional rights at all. So that means, for example, no 4th Amendment limits on search and seizure of corporate property. So, under this proposed Amendment, no one’s investments — not your stock portfolio, not your RRSP, not your pension plan — is immune from arbitrary seizure by the state. It also means that a corporation would have no right to due process when charged with a crime. The implications for shareholders and employees, here, are potentially disastrous. Under the People’s Rights Amendment, any corporation you’ve invested in, or where you work, could effectively be seized and shut down without cause, without trial, without explanation. This surely limits corporate power, but at enormous cost — namely an enormous increase in the power of the state. Not the people; the state.

I should also add that this Amendment seems also to apply also to unions, nonprofits, and churches. None of them would, under the People’s Rights Amendment, retain these rights against the state, and all would be enormously vulnerable.

But all of that only matters if Section 3 doesn’t exist, because Section 3, if taken seriously, guts the whole thing. Section 3 reasserts that people, human beings, do have rights, and that nothing in Section 2 can be construed as limiting those rights. So as the owner of a corporation, or as a shareholder in one, Section 3 assures you that your property — including presumably the property of the corporation you own, or the property of the corporation from which you derive dividends — cannot be subject to unreasonable search and seizure, and cannot be confiscated without due process. Whew!

The point here is that people, real flesh-and-blood people, rely on business corporations and other ‘corporate entities’ in a huge number of ways. They are how we make our living. They are the instruments of our collective success. Where the power of those instruments needs to be limited, as it surely sometimes does, it cannot be done by pulling the rug out from under individual, human liberties. And so if corporate power is to be reined in, it will have to be done through a mechanism considerably less clumsy than the People’s Rights Amendment.

Citigroup Shareholders, Say on Pay, and Moral Suasion

Shareholders at Citigroup have voted against the pay packages granted to the company’s top executives. Under Dodd-Frank, major firms are now required to hold shareholder votes on executive compensation at least once every three years. But the vote held Citigroup’s annual meeting on Tuesday was historic: it was the very first time that shareholders at a major financial firm have used this mechanism to express displeasure.

OK, now what? Well, that’s not entirely clear. Such votes are non-binding, and so the Board at Citigroup is legally entitled to ignore this recent vote entirely. But a widely-cited statement from the company includes the following assertion: “The Personnel and Compensation Committee of the Board will carefully consider their input as we move forward.” But really, what does that mean? And really, what should a Board of Directors do in the face of such feedback?

One problem is that a simple yea or nay vote is not very eloquent: there can be lots of reasons for saying “no” to a compensation package, and of course speculation is rampant. The Board (and its Personnel and Compensation Committee) now needs to talk to major shareholders — presumably it is already doing so — to find out what the problem is.

One analyst has been quoted as noting approvingly that this vote means the owners of big corporations are finally yanking the leash, a move towards getting things back under control. Mike Mayo, author of Exile on Wall Street, says that “[T[he owners of the big banks, namely the shareholders, are finally taking a greater amount of responsibility by speaking up.” The thinking here is that shareholders may have been objecting not just to Citigroup CEO Vikram Pandit’s $15 million dollar pay, but also to the $10 million retention payment awarded to him, and the general lack of correlation between Pandit’s pay and the company’s financial performance.

But then, while the idea that shareholders “own” the company is common, it is not uncontentious. The connection between most shareholders and the company is indeed pretty tenuous. And regardless of ownership claims, lots of people reject the idea that shareholders have any special role here, or that their voices should count for more than the voices of other stakeholder groups. Under such a view, a shareholder say-on-pay vote deserves little more than a shrug. After all, if shareholders are just one more stakeholder group, then evidence that they don’t approve of CEO pay is no more important than evidence of similar disapproval on the part of workers or suppliers or whomever.

But a shareholder vote has to count as more than just one more bit of moral suasion. For better or for worse, shareholders are, under most companies’ systems of governance, the ones to whom all insiders, including the CEO and Board of Directors, swear allegiance. Managers don’t promise to make a profit — such a promise would hardly be credible — but they do promise to at least try to make a profit, to have something left for shareholders after the bills are paid. It’s the one bit of accountability that every CEO, regardless of political persuasion, pays homage to.

Apple: The Ethics of Spending $100 Billion

What’s the best thing to do with a hundred billion dollars? Apple — the world’s richest company — gave its answer to just that question, when it announced yesterday how it will spend some of the massive cash reserve the company has accumulated.

Of course, spending the whole $100 billion was never on the agenda. The company needs to keep a good chunk of that money on-hand, for various purposes. Then there’s the fact that a big chunk of it is currently held by foreign subsidiaries, and bringing it back to the US to spend it would require Apple to pay hefty repatriation taxes. But any way you slice it, Apple has a big chunk of cash to spend, and so its Board faces some choices.

In the abstract, there are lots of things one could do with that much money. Financial analysts had rightly predicted that Apple company would decide to pay out a dividend (for the first time since 1995). Some were predicting bolder moves, like buying Twitter (which would use up a mere $12 billion). But what could Apple have done with that much money, aside from narrow strategic moves?

The money could have, in principle, been spent on various charitable projects. That amount of money could also do a lot towards helping developing countries combat and adapt to climate change. Or it could revolutionize the American education system. Closer to home, the company could spend a bunch on improving working conditions at its factories in China, conditions for which the company has been widely criticized. All of these, and many more, are (or rather were) among the possibilities.

But business ethics isn’t abstract; Apple’s Board faced a concrete question. And the Board has ethical and legal obligations to shareholders. Those aren’t its only obligations, but once workers are paid, warranties are honoured, expenses are covered, and relevant regulations are adhered to, the main remaining obligation is to shareholders.

Now, there’s a significant strain of thought that says that a company’s managers (and its Board) are not there just to serve the interests of shareholders, but also to carry out shareholders’ obligations. So, if you believe that Apple shareholders have an obligation to fight climate change or to promote education or to improve conditions for workers, then maybe it makes sense to think that the company ought to help shareholders to act on that obligation. But keep in mind that Apple’s shareholders are a rather amorphous group. Shares in corporations change hands incredibly frequently, and the interests and obligations of shareholders vary significantly, so a Board ‘represents’ shareholders (or acts as their agent) only in a rather abstract sense.

The alternative, of course, is for Apple’s Board to give itself some leeway, forget about what shareholders’ collective obligations might be, and go back to thinking abstractly about what to do with that big pile of cash. They can simply decide whether the shareholders’ financial interests outweigh their collective obligation to do some good with that money, and simply decide which of the various worthy causes it should go to. But of course, lots of people are rightly uncomfortable with the idea of well-heeled corporate boards arrogating to themselves that kind of power. The question for discussion, then, is this. Which is the greater evil? For corporations not to step up to the plate and contribute to social objectives, or for corporate leaders to presume to spend vast sums of money as if it were their own?

Insider Trading and Market Integrity

Cheng Yi Liang, a chemist for the US Food and Drug Administration, has been found guilty of Insider Trading and sentenced to 5 years in prison. (I first blogged about this case back in March, when Liang was arrested.)

Cheng Yi Liang, a chemist for the US Food and Drug Administration, has been found guilty of Insider Trading and sentenced to 5 years in prison. (I first blogged about this case back in March, when Liang was arrested.)

As it happens, the Liang verdict dovetailed nicely with the topic covered yesterday in the Management Ethics class I teach at the Ted Rogers School of Management. The class was led by a terrific guest speaker, compliance consultant and retired RBC compliance officer Georges Dessaulles.

The Liang case serves as a great example of one of the points Georges emphasized in his presentation, namely that when it comes to Insider Trading, highly-placed executives are far from the only concern. In the Freeport McMoran case in the mid-90’s, for example, the central figure was a consulting geologist, not an employee of the mining company itself. In the 2001 case related to Nortel’s acquisition of Clarify, the central figure was an executive working at a public relations firm that had a contract with Clarify. And now, in the Liang case, the guilty party not only didn’t work for the company in question, he didn’t have any contractual or other financial relationship with the company. Instead, he was a scientist at a regulatory agency. Other cases have involved administrative assistants, or even employees at companies printing corporate reports.

This highlights an important point about the ethics of insider trading. The stereotypical cases of insider trading involve executives, making use of undisclosed knowledge to gain an unfair advantage over outsiders in buying or selling stock. In taking unfair advantage, executives not only perpetrate a basic injustice, but also violate their duties to shareholders. But the kinds of cases cited above point to a different reason for the wrongness of insider trading. In the Freeport and Nortel cases, and now in the FDA case, the central figure wasn’t someone with direct obligations to corporate shareholders. There was thus no breach of fiduciary duty (at least not in the usual sense). What’s really at stake, in such cases, is the undermining of the basic principle of free-and-voluntary exchange on which the a free-market economy is based.

The challenge for organizations is to make sure that employees and contractors with access to sensitive information understand the definition of — and penalties for — insider trading. But that’s a serious challenge, especially at big companies. Better still would be for more people to understand the moral underpinnings of free markets quite generally, and to have the moral reasoning skills to figure out the rest from there.

If Facebook Were a Country, Would Zuckerberg Be King?

I’m serious. Is Mark Zuckerberg aiming to be the hereditary sovereign of the Kingdom of Facebook?

Amid all the ballyhoo about the Facebook IPO, concerns have arisen about the ownership structure — and, hence, governance structure — structure that the company’s plan implies. As Matt Yglesias recently outlined, the current plan implies considerable continuing power for Zuckerberg. Given the number of Class B shares he owns, along with proxies he controls, Zuckerberg effectively has “57 percent of the voting rights over the company.” In addition, his control will be transferred to whomever inherits his fortune.

Is this a good thing or a bad thing? A couple of points, both having to do with how Zuckerberg will use his power.

One is that, interestingly, Zuckerberg has (in a letter to investors) disavowed a focus on profits:

“Simply put: we don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services.

And we think this is a good way to build something. These days I think more and more people want to use services from companies that believe in something beyond simply maximizing profits….”

Some will rejoice at this. But of course, when a company says it’s going to aim at things beyond profits, there’s no particular reason to think that they’ll aim instead at goals you approve of. Facebook is a powerful company, grounded on a potent technology. Whomever controls it has the power to do a lot of good, or a lot of evil. And as I’ve pointed out before, Zuckerberg holds some dangerous views about, for instance, things like privacy.

Some of the comments under Yglesias’s piece have suggested that Yglesias exaggerates just how unique Facebook is in this regard. Other companies have been controlled by powerful central figures. Fair enough, but Facebook isn’t your average company. In a very real way, Facebook is becoming part of the infrastructure of modern life. In its role, it is more like a public utility than a private company. That puts the company — and its leader — in a very different position than, say, Ford or Exxon. Facebook really is more like a nation, and so he who controls it really is more like a political leader. This casts a very different light on how we evaluate not just the man, but the processes that are in place to guide his judgment.

Leave a comment

Leave a comment