Customizing Ethical Products

So-called “ethical” products are in the news again. This time, the controversy is over whether the fairtrade movement should expand to include certification of large farms.

A controversy like this serves to highlight the complexity of the notion of an “ethical” product. After all, any product has many different characteristics, and hence many different dimensions of ethical concern. Just for starters, two food products of the same kind (say, two different brands of coffee) might vary in terms of whether they are FairTrade certified or not, whether they are organic or not, whether they are from countries with bad human-rights records, and so on. So the choice we face isn’t just between the ethical brand and the “other” brand; it might well be between two brands with different combinations of more, or less, ethical characteristics.

So here’s a thought experiment. Imagine a world in which mass customization technology make it possible for you, by purchasing online, to hyper-customize the products you buy, according to various ethical characteristics. Imagine you could choose, with a click of your mouse, any or all of a range of characteristics. And to make things more interesting (and likely more realistic) let’s say that each additional characteristic you ask for implies some additional cost. After all, some “ethical” production processes are costly, and some certification schemes are costly. So let’s imagine, say, that each additional ethical characteristic you opt for results in a modest 2% increase in the price of the product.

Given the opportunity to buy such customized products, which ethical characteristics would you choose to pay for?

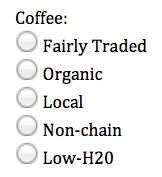

Consider, for example, what you would choose faced with a website that let you order coffee and gave you the following options:

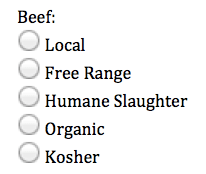

Or imagine being able to buy beef and to select from among the following characteristics:

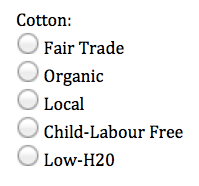

Or again, imagine being offered the following choice with regard to the cotton from which your newly-tailored shirt is to be made:

This thought experiment raises several questions. For you, the consumer, it raises the question of which combination of ethical values you really want — and would be willing to pay for — in your purchases. For purveyors of “ethical” consumer products, it first raises doubts about the term itself, and about how confident companies can be that they’ve already identified “the” characteristics that make up an ethical product. Consider the light this sheds on the case of so-called “ethical veal,” as discussed in a recent story from the Guardian. Sure, the veal referred to in that story is ethically better in at least one way. But have the people selling it cognizant of the range of characteristics that different people regard as essential to making a food product truly ethical?

Of course, the shopping scenario imagined above is science fiction for now. You can buy customized shoes online, and customized chocolate bars, but as far as I know foods customized ethically are not yet on sale. If they were, would that make the choice faced by ethical consumers easier, or harder?

Executive Compensation at a Regulated Monopoly

Protests broke out last week at the first annual shareholders’ meeting of Canadian energy company, Emera. Emera is a private company, traded on the Toronto Stock Exchange. But one of its wholly-owned subsidiaries, Nova Scotia Power, is the regulated company that supplies Nova Scotia with virtually all of its electricity.

The protest concerned the fact that several Emera and Nova Scotia Power executives had received substantial raises, despite the fact that Nova Scotia Power had just recently had to go to the province’s Utility and Review Board to get approval to raise the price it charges Nova Scotians for electricity. According to the utility, the rate hike was needed to add new renewable energy capacity to Nova Scotia’s grid. But protestors wondered if the extra cash wasn’t going straight into the pockets of wealthy executives.

The first thing worth pointing out for anyone not already aware is that practically no one thinks that anyone is doing executive compensation particularly well. Sure, most boards have Compensation Committees now, and many big companies engage compensation consultants to do the relevant benchmarking and to make recommendations. But no one is particularly confident in either the process or the results. So Emera’s board is far from alone in facing this kind of critique.

The second point worth making is that there are two very different kinds of stakeholders concerned in a case like this, but in this particular case they happen to overlap substantially. On one hand, there are Emera’s shareholders. They have an interest in making sure the company’s Comp Committee does its job, and sets executive compensation in a way that attracts, retains, and motivates top talent in order to produce good results. On the other hand, there are customers of Nova Scotia Power, ratepayers who want a cheap, stable supply of electricity. Now, as it happens, many of the vocal protestors at Emera’s annual meeting are members of both groups: they are shareholders in Emera and customers of Nova Scotia Power. But it is crucial to see that these are two separate groups, with very different sets of concerns. When this story is portrayed as a story about angry shareholders, this crucial distinction gets blurred. What’s good for shareholders per se is obviously not the same as what is good for paying customers. And, importantly, a company’s board of directors aren’t accountable to customers in the same way that they are to shareholders.

The final point to make about this is that, to observers of corporate governance, this is actually a “good news” story. As noted above, no one thinks executive compensation is handled very well. But despite that fact, corporate boards still face relatively little pushback from shareholders, and are relatively seldom held to account in this regard. There are of course exceptions (including a number of failed “say on pay” votes) but those exceptions prove the rule. And that’s unfortunate. In any ostensibly democratic system, it is a good thing when the voters take the time to show up and to ask hard questions. Even if no one is sure that such participation improves outcomes, it is an invaluable part of the process.

———-

(I was on CBC Radio’s Maritime Noon show to talk about this controversy. The interview is here.)

———-

HR Policies and Fundamental Justice

When employers terminate an employee as punishment for wrongdoing, it is important that they proceed in a way that pays attention to fundamental principles of justice. The firing can’t be arbitrary, or be carried out without sufficient evidence. The firing should be a penalty proportionate to the wrong committed — that is, the punishment should fit the ‘crime.’ And the employee to be terminated ought to be allowed a reasonable opportunity to respond to the accusations. These are fundamental ethical principles, ones that happen also to be entrenched to a greater or lesser degree in HR law.

In that regard, here’s an interesting story about a civil servant in Connellsville, Pennsylvania, who successfully appealed her dismissal, on the grounds that the right process hadn’t been followed. More specifically, she’s a city employee who stands accused of doing work on behalf of other employers on city time. Interestingly, the court that overturned City Council’s decision to fire her didn’t disagree with Council’s reasons — the court merely disagreed with the process that was followed. In particular, the employee hadn’t been given enough time to prepare for the Council meeting at which her case was considered and a guilty ‘verdict’ issued.

The key point to understand, though, isn’t about the legal standard the court applied. Or at least, the legal standard isn’t the only interesting part. Because the legal standard applied — one according to which someone accused of something deserves a decent amount of time to prepare a defence — isn’t just a legal principle, but also a fundamental principle of justice. It’s a moral principle that is embedded in our legal system, and that ought to have been embedded in Connellsville’s HR policies. In other words, the city’s policies ought to have stipulated that an employee accused of wrongdoing be given sufficient time to mount a defence before being asked to stand ‘trial.’

Last Friday I spoke at the annual Client Conference for the big Toronto HR law firm, Hicks Morley. The talk was entitled “The Ethical Core of HR Law.” The basic idea was one that is nicely illustrated by the story cited above. Laws exist to protect rights and to promote human wellbeing. Organizational policies are in a sense a kind of private law, albeit a kind of law designed to support achievement of organizational goals. Thus every policy an organization puts in place ought to be thought of as grounded in one or more ethical principles or values. Organizations ought to give as much thought to the ethical content of their policies as they do to promulgating and enforcing them.

Healthcare, Unions, and Selling Donuts to Canadians

Selling donuts to Canadians sounds so easy that it seems like the punch-line to a not-very-funny joke.

Apparently, however, it isn’t always such and easy thing to do. Or at least, not easy enough to support paying double the minimum wage to the people who serve the donuts. Witness the case of the three Tim Hortons kiosks at Windsor Regional Hospital (in Windsor, Ontario, just across the border from Detroit, MI). At Windsor Regional, the donut-and-coffee kiosks are a big drain (to the tune of a quarter-million dollars a year) rather than a source of revenue. Part of the reason, apparently, is that the servers who work there are paid over $20/hour — far above Ontario’s minimum wage of $10.25. The kiosks are in effect being driven under by their own employees.

Part of the complexity of this story lies in the fact that the donut kiosks in question are at a hospital. So this isn’t just a question of a profit-hungry capitalist at odds with unionized employees. The cost overrun in this case is borne by the hospital, a not-for-profit organization that must recoup the cost in other ways.

The donut kiosks, along with other food service outlets at the hospital, are part of the organization’s overall operating budget, part of the overall cost of providing healthcare to the people in the hospital’s catchment area. As Canadian health economist Robert Evans has often pointed out, every dollar spent on healthcare is a dollar of income for someone. The result is that there are plenty of people — some wealthy, and some not so wealthy — with a vested interest in not reducing the cost of healthcare. That’s not a matter of malice; it’s just a matter of math.

But of course, the salaries of unionized employees can only be part of the tale, here. If the three kiosks have, say, two employees on duty at a time, then paying each of them only minimum wage would still only save about $120,000 — which accounts for less than half of the shortfall. So it doesn’t make sense to point to the workers’ wages as “the” cause of the problem. The supply of donuts and coffee at Windsor Regional simply seems to be out of line with demand.

Of course, one way out would be for the coffee kiosks to raise their prices. That may or may not be permitted by Tim Hortons’ franchise agreement. But anyway, raising prices would mean pushing the burden onto patients and their families along with hospital staff. And at most hospitals, the on-site food outlets have a virtual monopoly, which puts customers at a serious disadvantage. It also means that demand at a hospital is less elastic, which means the hospital kiosks have more power to raise prices than a non-hospital donut seller would. And if you believe that the wage currently being paid is a fair one (by some measure), then that’s what should be done. They should raise prices to benefit employees at the expense of patients, families, and staff.

All if this just illustrates that idealism about fair wages has its limits. In a world of limited resources — i.e., the world we live in — giving more to one person often means taking more from someone else. The result is that you can’t argue for higher (or lower) wages without talking about prices. Wages are part of an economic system, and discussions of justice in one part of that system can’t ignore justice in the others.

———-

(Thanks to Prof. Alexei Marcoux for pointing out this story to me.)

MBA’s, Ethics, and the Facebook IPO

I’m an educator, so my natural bias is always to assume that yes, education matters. But it is in part because of this bias that it pains me when I see someone who is plainly overstating the case. And that’s the feeling I got when I read the Washington Post‘s Vivek Wadhwa asking, “Would the Facebook IPO have bombed if Mark Zuckerberg had an MBA?”

The answer — contrary to what Wadhwa argues — is “well, probably, yes!” The IPO almost certainly still would have bombed even if Facebook’s CEO had had an MBA. The fate of the company’s IPO depended a great deal on the way it was handled by Morgan Stanley, and on the appetite of institutional investors for the company’s stock. And that appetite depended a great deal on investors’ thinking on a lot of different questions, including things like whether Facebook still has room to grow or not. But there’s little readon to think that the educational pedigree of the CEO would have made much difference on its own.

It’s also worth pointing out that while Zuckerberg doesn’t have an MBA, he presumably has more than a few MBA’s working for him, and he certainly could afford to hire more. It’s pretty hard to make the case that the man himself having an MBA was utterly essential. So, while Wadhwa may well be right that having an MBA would mean that “Zuckerberg would have better understood the rules of corporate finance and capital markets,” it can hardly be argued that there was no one around with the relevant training to advise Zuckerberg on such matters.

Interestingly, Wadhwa twice mentions the importance of ethics in business, and rightly points to the ethics as being of central importance in an MBA education. But it’s far from clear just how Wadhwa thinks that is connected to the Facebook IPO having “bombed.”

Hopefully no one really thinks that getting an MBA is going to make you more ethical. If the ethics course you take during your MBA is a good one, it may do something to enrich and deepen the way you think about ethics, and to help you design and manage the kinds of systems that will help your employees act ethically. But even on the broadest and most inclusive understanding of the word “ethics,” there’s little reason to think that learning about ethics is going to make you better able to shepherd a company through an IPO. Nor is training in ethics any guarantee that individuals won’t engage in the kind of selective disclosure of information that is at the heart of the company’s post-IPO legal woes. The kind of ethics education that goes along with an MBA may well teach you more than you already knew about the nature of fiduciary duties and the importance of fostering trust, but an MBA-level ethics course is neither necessary, not sufficient, to make a business leader ethical.

POM Wonderful and Hearts vs Brains

The makers of POM Wonderful want you to use your heart, not your brain.

At least, that’s the distinct impression we get from the company’s recent battle with the US Federal Trade Commission. Last week, an administrative law judge for the FTC found that at least some of POM’s ads made “false and misleading” claims about the health benefits of the trendy, branded pomegranate juice. And the company is fighting back with a series of ads that, by quoting the judge out of context, makes it look like he actually looked favourably upon their product.

The tagline for these ads: “FTC v. POM: You be the judge”.

So POM wants you to be the judge. On the surface, that sounds like they want you to think for yourself. And who could complain about that? But context matters. So when the company is pushing back against the FTC’s assertion (and the court’s finding) that the health claims made on behalf of its juice just don’t stand up to scientific scrutiny, the implied message is that yes, you the consumer should decide, but you shouldn’t use your head in doing so. After all, if you used your head and thought it through rationally, you would want to look at the evidence. And, well, the evidence doesn’t look so good for POM. But the makers of POM, it seems, would rather you look inward instead of looking at the evidence. C’mon, you’ve tasted it. It’s delicious. It must be good for you. And you, dear customer, are smart enough to know that, right? Forget what the science says.

This kind of thing is arguably part of a larger social trend. See this recent essay by Joseph Heath and Andrew Potter, on the way politicians, in particular over the last decade, have found new ways to play fast-and-loose with the truth. Heath and Potter point out the new popularity of the trick of using stubborn repetition as means of bullying your way past awkward facts. A lie can be convincing, in particular when it feels right, when the claim being made fits with your world view or how you want the world to be. And who wouldn’t like to believe that a tasty serving of fruit juice could prevent heart disease or cancer?

The makers of POM are certainly not unique among advertisers wanting you to use your heart, rather than your brain. But they are unusually bold about it, going on the offensive and thumbing their noses at the people whose job it is to do the fact-checking. So consumers beware: when a company wants you not to take a hard look at the facts, it’s usually time to do just that.

Did Apple’s CEO Forego $75 million as a Matter of Principle?

There’s tone at the top, and then there’s tone at the top of the top. And when it comes to defining “top,” it’s hard to beat being the highest-paid CEO in the world, leading the most valuable company in the world. The man who occupies that post, of course, is Apple Inc.’s Tim Cook.

And recently, Cook made a pretty big move that might well do something to set the tone among high-end CEO’s. According to SEC filings, Cook reportedly has opted to take a pass on dividends he could have collected on over a million unvested shares. In total, that amounts to passing up about $75 million. Not that this is exactly going to leave Cook in the poorhouse — he’s paid a mind-boggling amount of money for the task of trying to fill Steve Jobs’s shoes. But still, it’s not trivial either. What should we make of it?

There are a couple of ways to think about this.

One has to do with shareholder confidence. Some have suggested that the decision is designed to show that Apple’s recent decision to pay a dividend wasn’t intended to benefit Cook himself. It is good for the investing public to know that the company is making decisions about things like dividends with the the best interest of shareholders in mind, rather than the best interests of the CEO. But then, Apple isn’t exactly suffering a crisis of shareholder confidence. If boosting the image of the company’s leadership is what you’re looking for, this might just be overkill.

But there’s another way to think of this, and that has to do with the good old-fashioned notion of honour. Call me a hopeless romantic, but I like to think that Cook’s decision might have something to do, as an unnamed source told the Telegraph, with setting an example for his fellow CEOs. Executive compensation has been in the spotlight almost continually for the last couple of years, and has even been the focal point of shareholder revolts. Maybe this is Cook’s way of saying, look, a high-end CEO doesn’t always have to squeeze every penny he can out of the company. And it’s entirely plausible, I think, that someone like Cook might make that decision — and send that signal — as a matter of principle.

“Honour” is the right moral category, here, because foregoing the cash is not something Cook is ethically obligated to do. He is fully within his rights, both legally and ethically, to take the dividend like other shareholders. But there’s arguably something good, something admirable, about attempting to shift the tone among high-end CEOs this way. It’s one thing to say that CEOs are overpaid. It’s quite another to set an example.

Will Cook’s move have any impact? Who knows. But it does seem like one more interesting attempt by the folks in Cupertino to get someone to “Think Different.”

Capitalism and Bad Behaviour

Contrary to what you have heard, there is nothing immoral about capitalism.

A couple of weeks back, the New York Times published a truly scandalous opinion piece by essayist William Deresiewicz with the provocative title, Capitalists and Other Psychopaths. The views expressed in the piece are not just false, but dangerous.

The central claim of Deresiewicz’s essay is that “capitalism is predicated on bad behavior.” This claim is entirely untrue. Capitalism in no way requires bad behaviour. Indeed, to function even moderately well, capitalist markets rely on a general pattern of basic goodwill and honesty of its participants. Commerce of any kind requires trust, and trust is predicated on the expectation that the other person is going to follow some basic rules of decent behaviour. The niceties of the rules that ought to govern business are up for debate, the basic need for some sort of rules is not. Capitalism, in other words, presumes ethics.

Deresiewicz is right of course that bad behaviour does go on within capitalist systems. That’s not exactly a news flash. Nor is it unique to capitalism. There’s no evidence that either feudalism or communism magically turns humans into selfless and cooperative purveyors of peace, love and understanding.

The beauty of a free market, as Adam Smith taught us, is that it can generate benefits even even among mean-spirited. The taxi driver who took me to the airport this morning doesn’t have to like me, and he doesn’t have to be a particularly lovely human being. All that’s necessary, in order for me to get to the airport, is that he wants to make a living. But in no way does capitalism require that people be vicious or even indifferent to each other’s fates. As Nobel laureate Ronald Coase put it, “The great advantage of the market is that it is able to use the strength of self-interest to offset the weakness and partiality of benevolence.” We are limited in our sympathies for others. The good news is that, in the marketplace, our commitment to our own welfare, and the welfare of those we hold dear, inspires a great deal of creative and industrious activity that has as its very useful side-effect the provision of benefits to others.

Deresiewicz’s essay also takes a particularly gratuitous pot-shot at business school education. “I always found the notion of a business school amusing,” he writes. “What kinds of courses do they offer? Robbing Widows and Orphans? Grinding the Faces of the Poor?” This may be a joke, but it’s a baffling one. Is business management really so trivial a task that it couldn’t possibly require any advanced training? (The old-guard communists thought so, and look where it got them.) Say what you will about business schools, there’s little doubt that the better ones, at least, teach a serious and difficult curriculum. Deresiewicz’s slam here is also terribly and unnecessarily insulting to millions of business school graduates who work diligently and honestly to produce a bewildering array of goods and services. Yes yes, we all know about Ken Lay and Bernie Madoff. Those men deserve, and have already received, ample criticism. But why impugn the honesty and integrity of every single executive, mid-level manager and accountant along the way?

The key to understanding Deresiewicz’s error is to see that he thinks ethics should be exactly the same in all situations. Not just present, but the same. The virtues of the marketplace, he suggests, should be the same as those of the Christian bible. The norms we apply to commercial exchange, he suggests, should also be (or include?) those of civic life. But does anyone really believe that? If a company rips you off should you really “turn the other cheek,” in good Christian fashion? Should Apple and Dell really debate the qualities of their competing products and then have us all vote for the one winning product that we will then all buy? To expect the same behaviour in the market as in a townhall meeting makes about as much sense as to expect people to behave on a football field the same way they do in a church pew.

It goes without saying that Deresiewicz is not alone in his misunderstanding of the fundamentals of capitalism. But his misunderstanding is especially fundamental, and especially corrosive. The really troubling thing about Deresiewicz critique is that it suggests that there’s nothing about capitalism worth saving. If capitalism is intrinsically unethical — if it has the immorality baked right in — then why try to fix it? Why try to make things work better? We all might as well just settle in and enjoy our smug cynicism. Because like a lot of really trenchant critics, Deresiewicz offers us no alternative.

Will Facebook’s IPO Bring New Public Responsibilities?

Today, with the advent of its much-anticipated IPO, Facebook, Inc. will be “going public.” From a legal and regulatory point of view, that’s a significant change, bringing for example new requirements for financial transparency. But what does it imply from an ethical point of view? The phrase “going public” here is somewhat misleading. The event doesn’t do anything as dramatic as changing Facebook from a private to a public entity. It simply means that shares in the company will now be available to members of the public, and traded on the publicly-accessible stock markets.

Regardless, many people already do think of Facebook as a “public” institution in some sense. They think of corporations in general as public institutions, with public responsibilities beyond just keeping their noses clean. The very act of incorporation, after all, requires a framework of public laws to enable it, as do key aspects of modern incorporation such as limited liability. The view here is that if the public allows, and indeed enables, incorporation, it has the right to expect something in return.

Many people also point to history: once upon a time, corporations were chartered by the government as instruments of the public good — to sail in search of treasure, to build bridges, and so on. Of course, the way things used to be is typically a pretty poor argument for how they ought to be today. It is, in general, a good thing that corporations are not now thought of as creatures of the state. If you’re an entrepreneur with a good idea, you don’t need to bow to a prince or bureaucrat to be allowed the privilege of incorporating. That is a good thing. We allow incorporation, and the limited shareholder liability that goes with it, because of the socially-useful stuff this allows corporations to do en route to building wealth for their shareholders.

So I think it is generally misguided to think of corporations as public entities, at least as this applies to corporations in general. Corporations are private entities, ones that play a role in an overall system — namely, the Market — which arguably exists to promote the public good in some sense. But to infer, from the notion that the Market has a role in promoting the public good, the notion that each corporation exists for that purpose, amounts to committing the ‘Fallacy of Division,’ the fallacy of assuming that the parts of a system necessarily share the characteristics of the system as a whole.

So Facebook isn’t, just by being a corporation, an instrument of the public good in any grand sense, and it won’t become one when it “goes public.”

But Facebook is not, in my view, a corporation just like any other. As I’ve argued before, there’s reason to think that a company like Facebook — public or not — has special obligations due to its role as a piece of communications infrastructure. It is such an integral part of so many people’s social lives and patterns of communication, and it has so few real competitors, that I think it is in some ways more like a public utility than like a private company.

From that point of view, the idea of Facebook going public is slightly more interesting. Because this quasi-utility is about to face a new set of pressures. Its managers (including especially CEO Mark Zuckerberg) will now be beholden to a greatly expanded constituency of shareholders. Of course, Facebook has long had shareholders, but they were far fewer in number. And those early shareholders were also different in terms of expectations and levels of patience. People who get in on the ground floor of a tech company like Facebook are speculating in a very significant way. They may have big dreams for their stake in the company, but they are less likely to demand growth on a quarterly basis the way shareholders in a widely-held company are likely to do.

The new wave of shareholders are likely to insist on ever-growing profits — this at a time when many people are expressing doubts about the company’s room for growth. How well the company will treat its customers in the face of such pressures is yet to be seen. For example, there are surely lots of ways for the company to make money by selling the right bits of the vast trove of information it currently has about its roughly 900 million users. Will the company sacrifice your privacy in pursuit of profits?

For better or for worse, the company may well be able to resist such temptations, because of the way control of the company is structured. As has been widely noted, Zuckerberg will still exercise nearly unfettered control. He will retain over 50% of voting stock, making him the controlling shareholder in addition to being both CEO and Chair of the Board. Whether that’s good or bad depends on how he exercises that power, and the goals he chooses to aim for. He has, for instance, has publicly disavowed profit as a primary motive. He’s been quoted as saying that, at Facebook, “we don’t build services to make money; we make money to build better services.” This implies, for instance, that Zuckerberg wouldn’t sell your private information just to make a buck. But — who knows? — he might conceivably do it for other reasons. But if all goes well, Zuckerberg’s profits-be-damned approach will act as a check on what might be seen as the baser impulses of the investing public. And if his own ambitions stray too much from the public good, then hopefully the ‘discipline of the market’ will act as a check on the tech visionary himself.

Should JPMorgan Fire the London Whale?

Would you fire an employee responsible for losing your company a couple billion dollars? I mean, hey, mistakes happen. But we’re talking two billion, here, with a “B”.

It’s not a hypothetical question, at least not for one major financial institution. As has been widely reported, JP Morgan Chase has now acknowledged that recent trading losses of two billion dollars are “somewhat related” to the controversial activities of a single London-based broker. The broker, whose real name is Bruno Iksil but who is often referred to as The London Whale, made enormous bets on U.S. corporate bonds…and lost.

I don’t think anyone has seriously suggested firing The Whale, at least not in public. But it does make you wonder. Even a company the size of JPMorgan can’t quite shrug off losses of that magnitude. And as others have pointed out, the hit to the company’s reputation may be more damaging, in the long run, than the short-run hit to its bottom line.

It’s worth noting that The London Whale was not a rogue trader. Indeed, his strategy was widely known, and apparently approved of by top executives at the company’s chief investment office.

Still, executive approval or no, it would be easy enough to make a scapegoat of The London Whale. But of course, that would be disingenuous, and the complicity of the Whale’s bosses is now public knowledge. And anyway, it’s entirely possible that the company will continue to see him as a valuable trader. He lost money this time around, but only insiders have the numbers to know how much he has made or lost for the company during his years there. And it’s entirely possible for even a losing bet to be regarded as one that it was smart to make in the first place.

There is also a public interest angle here. One of the key lessons of the last 4 years has been that innovative risk-taking by financial institutions can be a threat to the public good, not to mention the public purse. So even if The London Whale, and his overseers, aren’t destined to be axed by those who serve the company’s shareholders, that doesn’t mean they don’t collectively deserve our opprobrium, in addition to warranting stricter regulation.

Leave a Comment

Leave a Comment